All content on this site is intended for healthcare professionals only. By acknowledging this message and accessing the information on this website you are confirming that you are a Healthcare Professional. If you are a patient or carer, please visit the International Myeloma Foundation or HealthTree for Multiple Myeloma.

The mm Hub website uses a third-party service provided by Google that dynamically translates web content. Translations are machine generated, so may not be an exact or complete translation, and the mm Hub cannot guarantee the accuracy of translated content. The mm and its employees will not be liable for any direct, indirect, or consequential damages (even if foreseeable) resulting from use of the Google Translate feature. For further support with Google Translate, visit Google Translate Help.

The Multiple Myeloma Hub is an independent medical education platform, sponsored by Bristol Myers Squibb, GSK, Legend Biotech, Pfizer, and Roche. Funders are allowed no direct influence on our content. The levels of sponsorship listed are reflective of the amount of funding given. View funders.

Now you can support HCPs in making informed decisions for their patients

Your contribution helps us continuously deliver expertly curated content to HCPs worldwide. You will also have the opportunity to make a content suggestion for consideration and receive updates on the impact contributions are making to our content.

Find out more

Create an account and access these new features:

Bookmark content to read later

Select your specific areas of interest

View multiple myeloma content recommended for you

Classification and treatment of frail and ultra frail patients with multiple myeloma: challenges and future perspectives

Featured:

Multiple myeloma (MM) is a systemic condition with disease-related comorbidities manifesting in other organ systems, such as impaired renal function, immune dysregulation, and anemia. These comorbidities can affect the fitness of patients and their ability to tolerate more intense treatments. As discussed previously on the Multiple Myeloma Hub, age and frailty are subsequently demanding greater assessment and consideration whilst determining possible treatment strategies for patients with MM (available here) and their fitness for transplant (available here).

Here, we review an oral presentation, given on May 15, 2022, at the 8th World Congress on Controversies in Multiple Myeloma (COMy) by Sonja Zweegman,1 on the management of ultra-frail patients with MM, identifying potential conflict between the aims of MM treatment (e.g., length of survival) and the patients’ own priorities (e.g., quality of life). This builds on Zweegman’s prior work considering the assessment of frail patients with MM, which is discussed in the video below.

3 things you should consider when treating frail patients

Defining frailty in MM

Based on the assessment of age, activities of daily living (especially those considered fundamental), and disease-associated comorbidities, the International Myeloma Working Group Frailty Index (IMWG-FI) considers patients with a score ≥2 as frail. Consideration of these treatment groups has become a fundamental part of clinical trial design, including how to treat individual patients with MM with comorbidities, whether they are disease related or not.

Frailty in clinical trials

Analysis of the HOVON 123 study conducted by Zweegman and colleagues identified that while the IMWG-FI accurately identifies frail patients, there is a high degree of heterogeneity between frail patients in terms of the prevalence of cognitive or nutritional impairments or sarcopenia. Subsequent analysis of the patient cohort by actual score (e.g., 1, 2, 3, 4 or 5) rather than using a cut‑off of ≥2, revealed that patients with an IMWG-FI score of 2 had a treatment discontinuation rate closer to patients with a score of 1 than those with a score of 3 (Table 1). Subsequent analysis of the cohort using a cut‑off of ≥3 further identified that patients with an IMWG-FI of 2 had an overall survival and progression-free survival (PFS) statistically closer to intermediate-frail patients (IMWG‑FI of 1) than those with a score of 3–5. Based on this, Zweegman and colleagues proposed that patients with an IMWG-FI of ≥3 represent an “ultra-frail” cohort.

Table 1. Discontinuation rates of therapy according to IMWG-FI classification for patients in the HOVON 123 study*

|

CI, confidence interval; IMWG-FI, International Myeloma Working Group Frailty Index. |

||

|

IMWG-FI |

Discontinuation rate, % |

Odds ratio (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

|

1 |

33.8 |

1.00 (reference group) |

|

2 |

34.4 |

1.03 (0.47–2.50) |

|

3 |

57.9 |

2.67 (1.11–6.56) |

|

4 |

60.0 |

2.90 (0.94–9.40) |

|

5 |

81.8 |

8.58 (1.57–87.9) |

The impact of frailty on survival outcomes

Zweegman highlighted key findings from the MAIA trial (NCT02252172), which explored daratumumab with lenalidomide and dexamethasone (DRd) versus lenalidomide and dexamethasone (Rd). Using a study-specific frailty score (applied retrospectively using age, baseline Charlston comorbidity index, and Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status score), the MAIA investigators reported that PFS was better with DRd compared with Rd, irrespective of frailty score. However, after a 36.4‑month median follow-up, there was a reduced median PFS in frail patients for both DRd and Rd when compared to the other subgroups2:

- Frail patients: not reached (NR) vs 30.4 months (hazard ratio [HR], 0.62 ; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.45–0.85; p = 0.003)

- Intermediate patients: NR in both cohorts (HR, 0.53; 95% CI, 0.35–0.80; p = 0.0024)

- Fit patients: NR vs 41.7 months (HR 0.41, 95% CI 0.22–0.75, p = 0.0028)

Focusing on the outcomes for intermediate-fit patients defined by the IMWG-FI criteria, Zweegman presented data from a phase III clinical trial (NCT02215980), which enrolled only intermediate-fit newly diagnosed patients ineligible for autologous stem cell transplantation, and treated them with lenalidomide-dexamethasone followed by lenalidomide maintenance (Rd-R) or continuous lenalidomide-dexamethasone (Rd). After a median follow-up of 37 months (range, 27–45 months):

- median PFS was 20.2 months vs 18.3 months for the Rd-R- and Rd-treated patients, respectively (HR, 0.78; 95% CI, 0.55–1.1; p = 0.16).

When comparing both trials above and given the relevant differences in median PFS with Rd, Zweegman argues that the two study populations are distinct (and likely heterogeneous). It is argued that frailty assessment demands extra consideration and analysis since some frail patients perform closer to intermediate-fit patients and due to the potential for higher risk “ultra-frail” patients to skew results.

To further illustrate this need, Zweegman reflected on data from the HOVON 143 trial, which investigated ixazomib, daratumumab, and low-dose dexamethasone induction followed by ixazomib and daratumumab maintenance in IMWG-FI classified frail patients. The trial included a significant frail population.

- Of the 65 patients enrolled, 20% were deemed as frail based on age alone, 49% based on frailty parameters alone, and 31% based on age and frailty parameters.

- Reasons for treatment discontinuation before maintenance included progressive disease, intercurrent death, toxicity and adverse drug reactions, and non-compliance.

The median PFS for the overall and frailty subgroups can be seen in Table 2. Zweegman reported a median PFS from 13.8 months to 21.6 months, which again shows the heterogeneity within one pre‑defined frail subgroup.

Table 2. PFS outcomes from the HOVON 143 study*

|

CI, confidence interval; IMWG-FI, International Myeloma Working Group Frailty Index; PFS, progression-free survival. |

||

|

Group |

PFS, months |

95% CI, months |

|---|---|---|

|

Overall (frail by IMWG-FI) |

13.8 |

9.2-NR |

|

Frail based on age only |

21.6 |

9.2–NR |

|

Frail based other frailty parameters only |

13.8 |

7.8–NR |

|

Frail based on age and frailty parameters |

10.1 |

3.3–21.4 |

Conclusions and considerations for real-world management

The data and information presented by Zweegman support her argument that the “ultra-frail” population has not yet been identified within patients with MM, even when using the IMWG‑FI. Patients within the ultra-frail and frail groups are heterogeneous in terms of their individual functional and clinical morbidities. Careful consideration and subanalysis of IMWG-FI groups, especially groups 2 and 3, are necessary to identify patients at risk of inferior outcomes. While high response rates to treatment and improvements in quality of life indicate treatment is valuable to both frail and ultra-frail patients, discontinuation rates, toxicity, and early mortality remain high in these populations. Patient preferences must be considered, with the potential for significant discrepancies between physician and patient treatment priorities and outcomes.

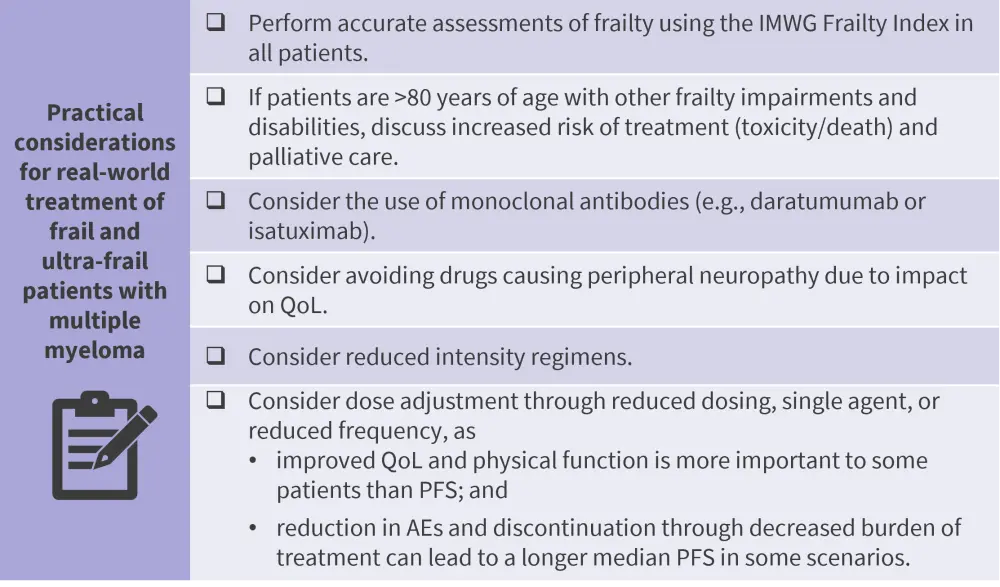

Figure 1. Practical considerations for real-world treatment of frail and ultra-frail patients with multiple myeloma presented by Sonja Zweegman*

AE, adverse event; IMWG, International Myeloma Working Group; PFS, progression-free survival; QoL, quality of life.

*Data from Zweegman.1

References

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statements:

The content was clear and easy to understand

The content addressed the learning objectives

The content was relevant to my practice

I will change my clinical practice as a result of this content

Your opinion matters

On average, how many patients with MGUS/smoldering MM do you see in a month?

Sonja Zweegman

Sonja Zweegman