All content on this site is intended for healthcare professionals only. By acknowledging this message and accessing the information on this website you are confirming that you are a Healthcare Professional. If you are a patient or carer, please visit the International Myeloma Foundation or HealthTree for Multiple Myeloma.

The mm Hub website uses a third-party service provided by Google that dynamically translates web content. Translations are machine generated, so may not be an exact or complete translation, and the mm Hub cannot guarantee the accuracy of translated content. The mm and its employees will not be liable for any direct, indirect, or consequential damages (even if foreseeable) resulting from use of the Google Translate feature. For further support with Google Translate, visit Google Translate Help.

The Multiple Myeloma Hub is an independent medical education platform, sponsored by Bristol Myers Squibb, GSK, Legend Biotech, Pfizer, and Roche. Funders are allowed no direct influence on our content. The levels of sponsorship listed are reflective of the amount of funding given. View funders.

Now you can support HCPs in making informed decisions for their patients

Your contribution helps us continuously deliver expertly curated content to HCPs worldwide. You will also have the opportunity to make a content suggestion for consideration and receive updates on the impact contributions are making to our content.

Find out more

Create an account and access these new features:

Bookmark content to read later

Select your specific areas of interest

View multiple myeloma content recommended for you

Are we nearer to effective care in the elderly MM population?

Multiple myeloma (MM) can give rise to a number of morbidities, such as impaired kidney function, anemia, bone disease, and immune dysfunction, all of which accelerate the process of aging.1 Current frailty assessments broadly consider performance scores, age, and comorbidities, but inconsistencies remain, and frailty assessment in clinical trials lacks uniformity and accuracy.1,2

Of the elderly MM population, fit patients represent just 30%, with the remainder of older patients falling into the intermediate-fit and frail categories.2 Talks by Gordon Cook at the European Myeloma Network Meeting and Sonja Zweegman at the 7th World Congress on Controversies in Multiple Myeloma (COMy) provided insights into novel trial designs and personalized treatment regimens centered around aging and frailty, not age, to better represent the majority of elderly patients with MM.

The Multiple Myeloma Hub previously provided a summary of the management of elderly patients with multiple myeloma and the value of the International Myeloma Working Group (IMWG) frailty index in defining transplant eligibility in elderly patients with MM. Why not take a look to set the scene for this article?

Elderly patients and treatment eligibility: IMWG frailty index2

The IMWG frailty index goes some way to identify patients who might benefit from particular treatments. Data from 869 patients across three EMN trials were utilized to develop the index, expanding beyond age to additional factors predictive of overall survival (OS) in patients with MM (Table 1). Scores of 0, 1, and ≥2 were derived as a classification for fit, intermediate-fit, and frail patients, respectively, which has further been associated with the probability of experiencing non-hematologic toxicities and treatment discontinuation.

Table 1. Factors significantly associated with OS and the basis of the IMWG frailty index*

|

ADL, activities of daily living; CCI, Charlson Comorbidity Index; CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; IADL, instrumental activities of daily living; IMWG, International Myeloma Working Group; OS, overall survival. |

|||

|

Factor |

HR (95% CI) |

p |

Score |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Age, years |

|

|

|

|

≤75 |

1 |

|

0 |

|

76–80 |

1.13 (0.76–1.69) |

0.549 |

1 |

|

>80 |

2.40 (1.56–3.71) |

<0.001 |

2 |

|

ADL |

|

|

|

|

>4 |

1 |

|

0 |

|

≤4 |

1.67 (1.08–2.56) |

0.020 |

1 |

|

IADL |

|

|

|

|

>5 |

1 |

|

0 |

|

≤5 |

1.43 (0.96–2.14) |

0.078 |

1 |

|

CCI |

|

|

|

|

≤1 |

1 |

|

0 |

|

≥2 |

1.37 (0.92–2.05) |

0.125 |

1 |

Challenges with current clinical trial design

Identifying biomarkers of frailty has been an important step towards refining clinical trial design. Of particular interest are those involved in cellular and immune senescence, as well as biomarkers impacting body composition. Cook and Zweegman differentiate between prognostic and predictive biomarkers, describing the current status of the IMWG frailty index as solely prognostic due to the lack of data from randomized clinical trials.1,2

At present, sub-analyses, non-randomized trial data, and expert opinions are the extent of information surrounding the treatment of frail patients with MM. To establish the value of frailty scoring as a predictive marker, clinical trials must be designed to include the FRAIL population and consider frailty scores.2

There is, however, some data available for the intermediate-fit MM population. Zweegman discusses the outcomes of patients treated with lenalidomide plus dexamethasone in the phase III MAIA trial (control arm) vs a trial performed in intermediate-fit patients that were more representative of the real-world population. The regimen demonstrated a median progression-free survival (PFS) of 31.9 months in patients aged >75 years in the MAIA trial and 20.2 months in the trial with intermediate-fit patients.2 Herein lies the question, why are patient outcomes inferior in the real-world setting? This brings us back to the underrepresentation of elderly patients in pivotal clinical trials.

Studies inclusive of elderly patients have highlighted poor outcomes in this population, and inferior outcomes were evidenced by the HOVON 87 and HOVON 123 trials, which demonstrated a four-fold increase in toxicity-related deaths in patients over the age of 80 years. However, a proportion of the elderly population may be eligible for standard therapy, and identifying these individuals is essential for optimal outcomes.2 Together, these findings emphasize the requirement to look beyond the age in clinical trials, and the below studies signify a step towards improving personalized care in MM.

Hovon 1432,3

The Hovon 143 study (EudraCT 2016-002600-90) represents the first randomized clinical trial designed to exclusively evaluate patients with MM who have been classified as frail as per the IMWG frailty index. The phase II trial is investigating the efficacy and tolerability of ixazomib-daratumumab-low-dose-dexamethasone (Ixa-Dara-dex) in frail patients with newly diagnosed MM.

HOVON 143: ixazomib, daratumumab & low-dose dexamethasone for unfit & frail patients with NDMM

The treatment regimen, consisting of nine cycles of induction therapy followed by 8-week cycles of maintenance therapy, demonstrated a high overall response rate of 78% (36% very good partial response or better) and improved quality of life in this difficult to treat population. However, survival rates were negatively impacted by toxicity-related treatment discontinuation and early mortality, translating into a PFS of 13.8 months and a 12-month OS rate of 78%. Patients defined as frail based on age alone demonstrated a median PFS and a 12-month OS of 21.6 months and 92%, respectively. These data highlight the need for tailored treatment and a more accurate definition of the frail population.3

IFM 2017-032

As also emphasized by the Hovon 143 study, to further improve treatment personalization, it may be necessary to omit drugs that give rise to side effects, especially in the frail population. Due to poor tolerability of dexamethasone, the phase III IFM 2017-03 trial (NCT03993912) has been designed to compare a dexamethasone-free regimen (lenalidomide plus daratumumab by subcutaneous injection) vs lenalidomide plus dexamethasone in frail subjects with newly diagnosed MM. The phase III trial is being conducted in France and is currently recruiting participants.

FiTNEsS1

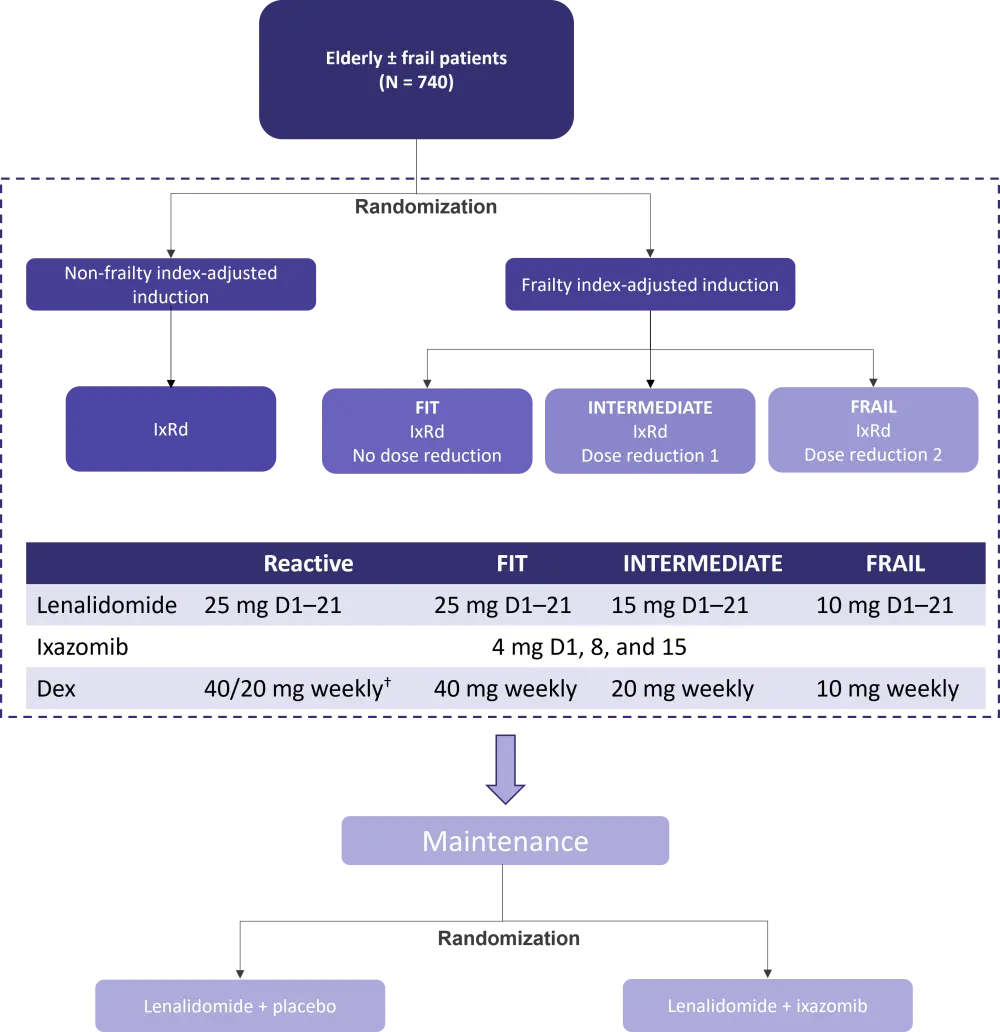

The Myeloma XIV: FiTNEsS (frailty-adjusted therapy in transplant non-eligible patients with symptomatic myeloma) study (NCT03720041) represents a significant step in determining the predictive value of a novel frailty risk score: the UK Myeloma Research Alliance Myeloma Risk Profile4. Initiated in the United Kingdom, FiTNEsS was designed to evaluate the feasibility and efficacy of upfront frailty index-adjusted induction therapy (Figure 1). Under evaluation is the oral triplet regimen, ixazomib-lenalidomide-dexamethasone: the investigators hope to see a significant toxicities reduction with the adaptive treatment strategy, which would translate into fewer early treatment discontinuations. Thus, more patients would arrive at the maintenance phase, receive a doublet maintenance therapy, and overall, achieve a longer PFS.

Figure 1. Myeloma XIV: FiTNEsS study design*

D, day, Dex, dexamethasone; IxRd, ixazomib-lenalidomide-dexamethasone.

*Adapted from Cook1 and data from Clinicaltrials.gov.5

†40 mg weekly for participants aged ≤75 years or 20 mg weekly for participants aged >75 years.

Conclusion

Despite the significant progress in treatment options for elderly patients with MM, outcomes for patients classed as frail remain suboptimal. Early data suggest that monoclonal antibodies are a viable approach to treating the unfit population, with encouraging results independent of frailty. In the case of intensive drugs, there is an obvious need for dose adjustment or even omission in this population.1,2 The recent shift in approach to clinical trial design is encouraging and shows promise to reduce toxicity-related deaths and improve survival in the frail population. Furthermore, the ongoing research will help to establish frailty assessment as an essential tool during diagnostic work-up and to guide treatment decisions.

References

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statements:

The content was clear and easy to understand

The content addressed the learning objectives

The content was relevant to my practice

I will change my clinical practice as a result of this content

Your opinion matters

On average, how many patients with MGUS/smoldering MM do you see in a month?