All content on this site is intended for healthcare professionals only. By acknowledging this message and accessing the information on this website you are confirming that you are a Healthcare Professional. If you are a patient or carer, please visit the International Myeloma Foundation or HealthTree for Multiple Myeloma.

The mm Hub website uses a third-party service provided by Google that dynamically translates web content. Translations are machine generated, so may not be an exact or complete translation, and the mm Hub cannot guarantee the accuracy of translated content. The mm and its employees will not be liable for any direct, indirect, or consequential damages (even if foreseeable) resulting from use of the Google Translate feature. For further support with Google Translate, visit Google Translate Help.

The Multiple Myeloma Hub is an independent medical education platform, sponsored by Bristol Myers Squibb, GSK, Johnson & Johnson, Legend Biotech, Pfizer, Roche, and Sanofi. The levels of sponsorship listed are reflective of the amount of funding given. View funders.

Now you can support HCPs in making informed decisions for their patients

Your contribution helps us continuously deliver expertly curated content to HCPs worldwide. You will also have the opportunity to make a content suggestion for consideration and receive updates on the impact contributions are making to our content.

Find out more

Create an account and access these new features:

Bookmark content to read later

Select your specific areas of interest

View multiple myeloma content recommended for you

Weighing up PFS and OS in the DETERMINATION trial: Re-evaluating the role of transplant in myeloma

With the advent of novel therapies, the standard treatment for multiple myeloma (MM) has changed for better outcomes.1,2 The role of autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (auto‑HSCT) is also evolving, and the most appropriate combination for induction and maintenance therapy in patients with newly diagnosed MM (NDMM) is continuously being challenged.

The Intergroupe Francophone du Myélome (IFM) 2009 trial (NCT01191060), amongst other studies, demonstrated superior progression-free survival (PFS) with the use of a triplet induction therapy followed by auto-HSCT. Quadruplet combinations are now also available, with potential for a more risk-adapted frontline therapeutic strategy. However, there is a general agreement on the key role of auto-HSCT for eligible patients. Several studies have addressed establishing both early and delayed transplant approaches to increase PFS and overall survival (OS), as well as determining how individual patients may benefit.1,2

During the European Hematology Association (EHA) 2022 Congress1 and the 2022 American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) Annual Meeting,2 Paul Richardson presented results of the primary analysis of the phase III DETERMINATION trial (NCT01208662), which is investigating the efficacy of delayed versus early transplant. Richardson et al. 3 also recently published these results in The New England Journal of Medicine. The DETERMINATION trial was originally designed as a parallel study to the IFM trial but later amended to include lenalidomide maintenance therapy until disease progression based on the results of the CALGB-100104/Alliance trial (NCT00114101).1,2

Study design

The DETERMINATION trial is a phase III, multicenter, randomized controlled trial in patients aged 18–65 years with NDMM who had an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of 0–2.4

Patients were stratified according to International Staging System disease stage and cytogenetic risk profile and randomized to the treatment schedule,1,2 as shown in Figure 1.

The primary endpoint was PFS. Secondary endpoints included response rates, duration of response (DOR), time-to-progression, OS, quality of life (QoL), and safety.1,2

Figure 1. Treatment schedule*

Auto-HSCT, autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation; C, cycle; d, dexamethasone; ISS, International Staging System; R, lenalidomide; V, bortezomib.

*Adapted from Richardson.1,2

†R maintenance: months 1–3, 10 mg/day; month 4 onwards, 15 mg/day.

Results1,2

Baseline characteristics

A total of 722 patients were included, with a median age of 57 years and 55 years in the RVd-alone and RVd + auto-HSCT arms, respectively. Overall, almost 19% of trial participants had an ethnicity of Black African American, which is the highest percentage so far in a phase III randomized MM trial (Table 1).

Table 1. Baseline characteristics*

|

auto-HSCT, autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation; BMI, body mass index; ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; F, female; IQR, interquartile range; ISS, International Staging System; M, male; R-ISS, revised ISS; RVd, lenalidomide, bortezomib, and dexamethasone. |

||

|

Characteristics, % (unless stated otherwise) |

RVd-alone |

RVd + auto-HSCT |

|---|---|---|

|

Median age (IQR), years |

57 (25–66) |

55 (30–65) |

|

Male/female |

56.6/43.4 |

58.9/41.1 |

|

Ethnicity |

|

|

|

White, Caucasian |

76.4 |

75.8 |

|

African American |

18.8 |

18.4 |

|

BMI |

|

|

|

<25 |

22.4 |

22.2 |

|

25 to <30 |

39.5 |

34.8 |

|

≥30 |

38.1 |

43.0 |

|

ECOG PS |

|

|

|

0 |

42.9 |

45.1 |

|

1 |

49.6 |

44.2 |

|

2 |

7.6 |

10.7 |

|

ISS disease stage |

|

|

|

I |

49.9 |

50.4 |

|

II |

36.4 |

36.7 |

|

III |

13.7 |

12.9 |

|

R-ISS disease stage† |

|

|

|

I |

30.9 |

31.2 |

|

II |

60.7 |

62.6 |

|

III |

8.4 |

6.2 |

|

Cytogenetics |

|

|

|

High risk‡ |

19.8 |

19.4 |

|

Standard risk |

80.2 |

80.6 |

|

Cytogenetics high risk |

|

|

|

t(4;14) |

9.6 |

8.2 |

|

t(14;16) |

3.0 |

4.4 |

|

del(17p) |

11.4 |

10.0 |

Treatment exposure

The median duration of all treatment from randomization was 36.1 months vs 28.2 months and the median duration of lenalidomide maintenance was 41.5 months vs 36.4 months in the RVd + auto‑HSCT and RVd-alone arms, respectively. The median proportion of maintenance cycles with an average lenalidomide dose ≥10 mg was higher in the RVd-alone arm compared with the RVd + auto-HSCT arm (87% vs 60%, respectively).

Efficacy

At a median follow-up of 76 months, the primary endpoint was met with a net gain of >21 months for the median duration of PFS with frontline auto-HSCT. Both I median duration of PFS and 5-year PFS were higher in the RVd + auto-HSCT arm versus the RVd alone arm, demonstrating a 53% increased risk of progression or death with RVd alone, as shown in Figure 2. PFS for prespecified key groups are shown in Table 2.

Figure 2. Median PFS and 5-year PFS in each arm*

auto-HSCT, autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation; HR, hazard ratio; PFS, progression-free survival; RVd, lenalidomide, bortezomib, and dexamethasone.

*Data from Richardson.1,2

Table 2. PFS by subgroup*

|

auto-HSCT, autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation; BMI, body mass index; CI, confidence interval; FISH, fluorescence in situ hybridization; HR, hazard ratio; ISS, International Staging System; NR, not reported; R-ISS, revised ISS; RVd, lenalidomide, bortezomib, and dexamethasone. *Adapted from Richardson.1,2 |

|||

|

Subgroup, months |

RVd-alone |

RVd + auto-HSCT |

HR (95% CI)† |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Ethnicity |

|

|

|

|

White/Caucasian |

44.3 |

67.2 |

1.67 (1.29–2.15) |

|

Black/African American |

NR |

61.4 |

1.07 (0.61–1.89) |

|

Other |

38.1 |

NR |

3.40 (1.00–11.5) |

|

BMI |

|

|

|

|

<25 |

33.6 |

NR |

2.60 (1.56–4.31) |

|

25 to <30 |

52.3 |

64.3 |

1.24 (0.86–1.80) |

|

≥30 |

45.8 |

64.4 |

1.41 (0.98–2.02) |

|

ISS |

|

|

|

|

I |

52.0 |

NR |

1.83 (1.32–2.54) |

|

II |

46.2 |

62.5 |

1.38 (0.96–1.96) |

|

III |

40.3 |

35.9 |

1.14 (0.64–2.01) |

|

R-ISS |

|

|

|

|

I |

59.1 |

NR |

1.38 (0.90–32.12) |

|

II |

40.9 |

67.5 |

1.63 (1.22–2.19) |

|

III |

22.2 |

32.5 |

0.96 (0.43–2.13) |

|

FISH |

|

|

|

|

High risk |

17.1 |

55.5 |

1.99 (1.21–3.26) |

|

t(4;14) |

19.8 |

56.5 |

2.72 (1.19–6.24) |

|

del(17p) |

16.3 |

41.3 |

1.44 (0.76–2.73) |

|

Standard risk |

53.2 |

82.3 |

1.38 (1.07–1.79) |

Patients in the RVd + auto-HSCT arm also showed a significant improvement in 5-year time-to-progression compared with the RVd-alone arm (58.4% vs 41.6%; HR, 1.66; p < 0.001). The post hoc sensitivity analysis showed an improved median event-free survival in the RVd + auto-HSCT arm compared with the RVd-alone arm (47.3 months vs 32 months; HR, 1.23).

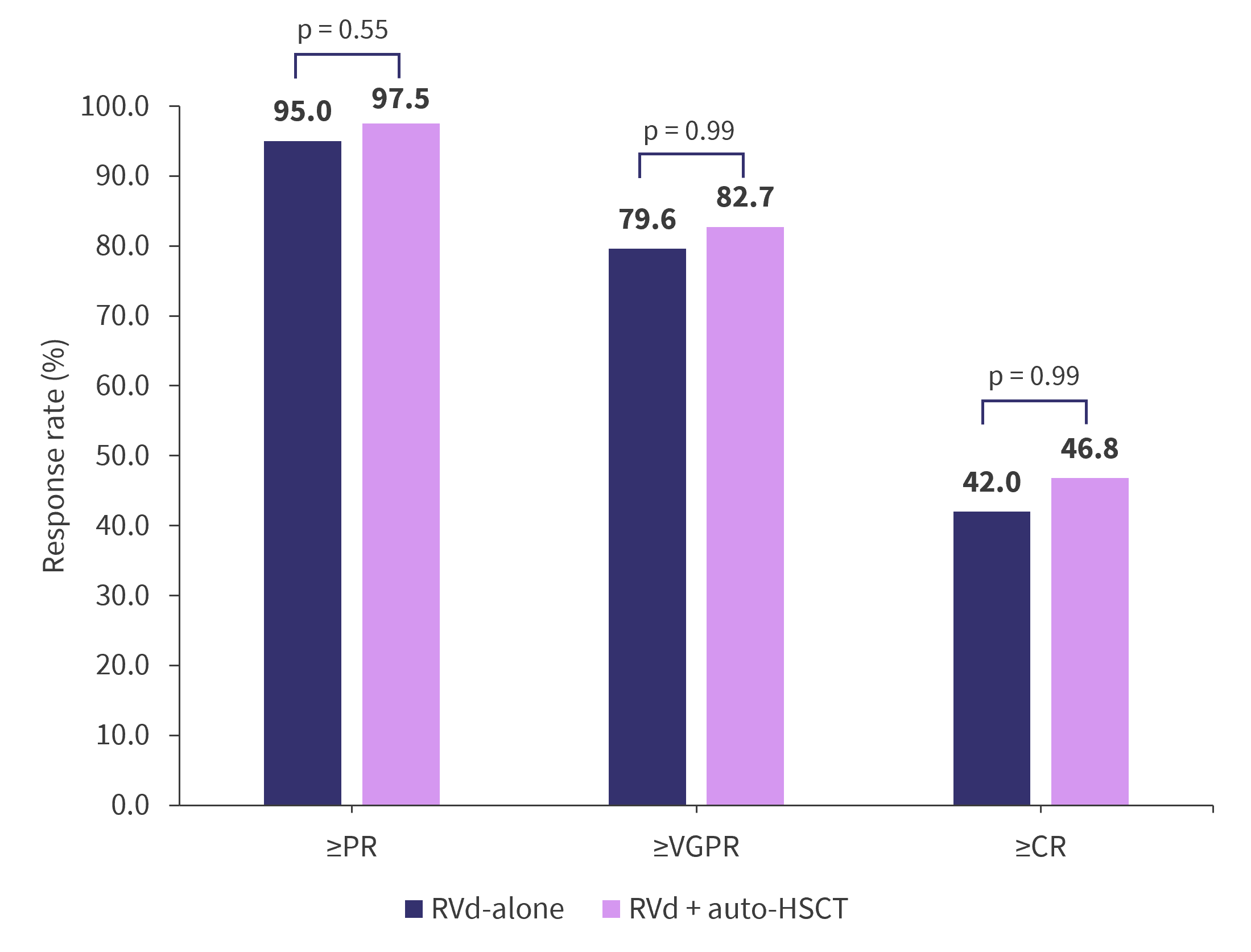

The response rates were similar in the RVd + auto-HSCT and RVd-alone arms, except when analyzing rates of elimination of minimal residual disease (MRD), as shown in Figure 3. Interestingly, the median DOR was statistically longer in patients achieving at least a partial response in the RVd + auto‑HSCT arm compared with RVd-alone arm (56.4 months vs 38.9 months; HR, 1.45; p = 0.003). However, the difference in 5-year DOR narrowed and was no longer statistically significant in patients achieving at least a complete response (60.6 months vs 52.9 months; HR, 1.35; p = 0.698).

Figure 3. Response rates*

Auto-HSCT, autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation; CR, complete response; OR, odds ratio; PR, partial response; RVd, lenalidomide, bortezomib, and dexamethasone; VGPR, very good partial response.

*Adapted from Richardson.1,2

The preliminary analysis evaluating the correlation between PFS and MRD status at the start of maintenance therapy in 198 patients showed a higher rate of MRD negativity in the RVd + auto-HSCT arm compared with the RVd-alone arm (54.4% vs 39.8%; odds ratio, 0.55). Of note, the 5-year PFS was similar among the two arms in patients achieving MRD negativity; however, in patients with MRD positivity, the median PFS was longer in the RVd + auto‑HSCT arm compared with the RVd-alone arm (Figure 4).

Figure 4. PFS depending on MRD status*

auto-HSCT, autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation; HR, hazard ratio; PFS, progression-free survival; RVd, lenalidomide, bortezomib, and dexamethasone.

*Data from Richardson.1,2

With the follow-up period approaching nearly 7 years, the 5-year OS in the RVd + auto-HSCT arm and RVd-alone arm was similar (80.7% vs 79.2%; HR, 1.10; p = 0.99), warranting further follow-up.

Safety

Grade ≥3 treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs), as well as hematologic TEAEs, were significantly higher in the RVd + auto-HSCT arm compared with the RVd alone arm (Table 3). The occurrence of serious adverse events was also higher in the RVd + auto-HSCT arm compared with the RVd-alone arm, both prior (47.1% vs 40.3%) and during (16.6% vs 11.3%) maintenance therapy.

Table 3. TEAEs of Grade ≥3*

|

auto-HSCT, autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation; RVd, lenalidomide, bortezomib, and dexamethasone; TEAEs, treatment-emergent adverse events. |

||

|

TEAE, % |

RVd-alone |

RVd + auto-HSCT |

|---|---|---|

|

Any |

78.2 |

94.2 |

|

Any hematologic |

60.5 |

89.9 |

|

Any Grade 5 (fatal) TEAE |

0.3 |

1.6† |

|

|

||

|

Neutropenia |

42.6 |

86.3 |

|

Thrombocytopenia |

19.9 |

82.7 |

|

Leukopenia |

19.6 |

39.7 |

|

Anemia |

18.2 |

29.6 |

|

Hypophosphatemia |

9.5 |

8.2 |

|

Lymphopenia |

9.0 |

10.1 |

|

Neuropathy |

5.6 |

7.1 |

|

Pneumonia |

5.0 |

9.0 |

|

Febrile neutropenia |

4.2 |

9.0 |

|

Diarrhea |

3.9 |

4.9 |

|

Fatigue |

2.8 |

6.0 |

|

Fever |

2.0 |

5.2 |

|

Nausea |

0.6 |

6.6 |

|

Mucositis oral |

0 |

5.2 |

The 5-year cumulative incidence of any secondary primary malignancies (SPM) was similar in the RVd + auto‑HSCT and RVd-alone arms at 10.75% and 9.68%, respectively; however, there was a higher occurrence of hematologic SPM, particularly acute myeloid leukemia/myelodysplastic syndromes, in the RVd + auto-HSCT arm (5-year cumulative incidence of 3.53%).3 At data cutoff, among the patients with hematologic SPM, seven patients out of nine in the RVd-alone arm and eight patients out of 13 in the RVd + auto-HSCT arm were alive.1

Quality of life

The mean change from baseline for European Organization for the Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire (EORTC QLQ-C30) global health status score was significantly lower in the RVd + auto-HSCT arm after transplantation compared with the RVd-alone arm (p < 0.0001), but it improved to similar scores before maintenance.3

Subsequent therapy

Subsequent therapy was received by 79.6% and 69.6% of patients in the RVd-alone and RVd + auto‑HSCT arms, respectively. Among the subsequent therapies used, monoclonal antibodies, such as daratumumab, elotuzumab, and isatuximab, were used more in the RVd + auto-HSCT arm. Only 28% of patients from the RVd-alone arm received auto-HSCT at any time following the end of study treatment.

Conclusion

This phase III trial demonstrates that early transplant offers a significantly superior PFS. It also demonstrates the clinical benefit, including a tolerable safety profile of long-term lenalidomide maintenance in both arms. There was no OS benefit after a median follow-up of >6 years. Of note, the higher rate of MRD-negative response in the RVd + auto-HSCT arm was associated with better outcomes. Although adverse events reported with RVd + auto-HSCT were considered manageable, it showed significantly higher rates, particularly in hematologic toxicity. In addition, the evidence of hematologic SPM indicates further investigation is required. The QoL was significantly reduced in the RVd + auto-HSCT arm but improved throughout the maintenance phase.

The decision of early or delayed auto-HSCT is dependent on several factors, such as patient preference, inability to store stem cells, or fewer treatment options available. Maintenance therapy is an important part of MM treatment but should be used with caution to minimize toxicity. Lastly, the findings from the DETERMINATION trial should be interpreted considering both the induction and maintenance therapy.

Next steps and future directions

With regards to the next steps for the DETERMINATION trial, additional analyses of MRD and evaluation of patient- and disease-related factors, including race, body mass index, and cytogenetics, will be important. Prospective whole-genome sequencing is a part of the trial and will inform the pattern of high-risk group resistance to treatment and low response rate, as well as the mutational burden at progression and/or relapse. Additional analyses of QoL, application of treatment to real-word settings, and health economics, including healthcare utilization, are planned.

In terms of future directions for treatment in patients with NDMM, there is a plethora of well-established treatments such as quadruplet therapy, chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy, bispecific antibodies, antibody–drug conjugates, and next-generation novel agents, which provides opportunities to improve outcomes in this population. Auto-HSCT may be beneficial in selected patient groups, particularly in those with residual disease. There may be a shift away from dividing patients based on their transplant eligibility in the future with a need to individualize the timing of transplant based on age, risk status, patient preference, and feasibility. With the arrival of novel therapies and even more agents on the horizon, there may be a limited role for auto-HSCT in the treatment of MM.

References

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statements:

The content was clear and easy to understand

The content addressed the learning objectives

The content was relevant to my practice

I will change my clinical practice as a result of this content