All content on this site is intended for healthcare professionals only. By acknowledging this message and accessing the information on this website you are confirming that you are a Healthcare Professional. If you are a patient or carer, please visit the International Myeloma Foundation or HealthTree for Multiple Myeloma.

The mm Hub website uses a third-party service provided by Google that dynamically translates web content. Translations are machine generated, so may not be an exact or complete translation, and the mm Hub cannot guarantee the accuracy of translated content. The mm and its employees will not be liable for any direct, indirect, or consequential damages (even if foreseeable) resulting from use of the Google Translate feature. For further support with Google Translate, visit Google Translate Help.

The Multiple Myeloma Hub is an independent medical education platform, sponsored by Bristol Myers Squibb, GSK, Legend Biotech, Pfizer, and Roche. Funders are allowed no direct influence on our content. The levels of sponsorship listed are reflective of the amount of funding given. View funders.

Now you can support HCPs in making informed decisions for their patients

Your contribution helps us continuously deliver expertly curated content to HCPs worldwide. You will also have the opportunity to make a content suggestion for consideration and receive updates on the impact contributions are making to our content.

Find out more

Create an account and access these new features:

Bookmark content to read later

Select your specific areas of interest

View multiple myeloma content recommended for you

FORTE trial update: Carfilzomib-based induction and maintenance therapy for patients with NDMM

The current standard of care for young and fit patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma (NDMM) is bortezomib-based induction followed by high dose (200 mg/m2) melphalan and autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT), followed by maintenance treatment with lenalidomide monotherapy.1 The FORTE trial (NCT02203643) evaluated the efficacy and safety of carfilzomib, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone (KRd) induction followed by high dose melphalan and ASCT compared with other K-based induction regimens in patients with NDMM. A previous subanalysis demonstrated a lower risk for early relapse, a higher rate of deep responses, and sustained minimal residual disease (MRD) with KRd plus ASCT compared with KRd alone. The subanalysis results were corroborated by a phase II trial (NCT01816971), which demonstrated that ASCT plus KRd for NDMM led to rapid and durable responses that are further improved following extended KRd maintenance.

Updated results from the FORTE trial were recently published in Lancet Oncology by Francesca Gay et al.1 and are summarized below.

Study design

Between February 23, 2015, and April 5, 2017, a total of 477 patients were enrolled in the FORTE trial. This was a multicenter, open-label, randomized, phase II trial for patients with NDMM who were eligible for transplant, aged ≤65 years, and with symptomatic, measurable disease.

From the 477 patients, 158 were allocated to KRd plus ASCT, 157 to 12 KRd cycles (KRd12), and 159 to carfilzomib + cyclophosphamide + dexamethasone (KCd) plus ASCT. At the end of consolidation, 356 patients were eligible for maintenance treatment and were subsequently randomized to carfilzomib + lenalidomide (n = 178) or lenalidomide monotherapy (n = 178). Patient characteristics are shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Baseline demographics and disease characteristics*

|

ASCT, autologous stem cell transplantation; IQR, interquartile range; ISS, International Staging System; KCd, carfilzomib + cyclophosphamide + dexamethasone; KR, carfilzomib + lenalidomide; KRd, carfilzomib + lenalidomide + dexamethasone; KRd12, 12 KRd cycles; R, lenalidomide. |

|||||

|

Variable |

Induction, intensification, and consolidation |

Maintenance |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

KRd plus ASCT |

KRd12 |

KCd plus ASCT |

KR |

R |

|

|

Median age (IQR), years |

57 (52–62) |

57 (51–62) |

57 (52–62) |

56 (52–62) |

57 (51–62) |

|

≥60 years, % |

39 |

38 |

39 |

35 |

37 |

|

Female, % |

45 |

44 |

45 |

43 |

49 |

|

ISS, % |

|

|

|

|

|

|

I |

51 |

51 |

50 |

54 |

55 |

|

II |

35 |

29 |

32 |

29 |

34 |

|

III |

15 |

20 |

18 |

17 |

11 |

Primary study endpoints

- The number of patients that reached at least a very good partial response with KRd versus KCd as induction therapy.

- Progression-free survival (PFS) rate with carfilzomib + lenalidomide compared with lenalidomide alone as maintenance therapy.

First randomization

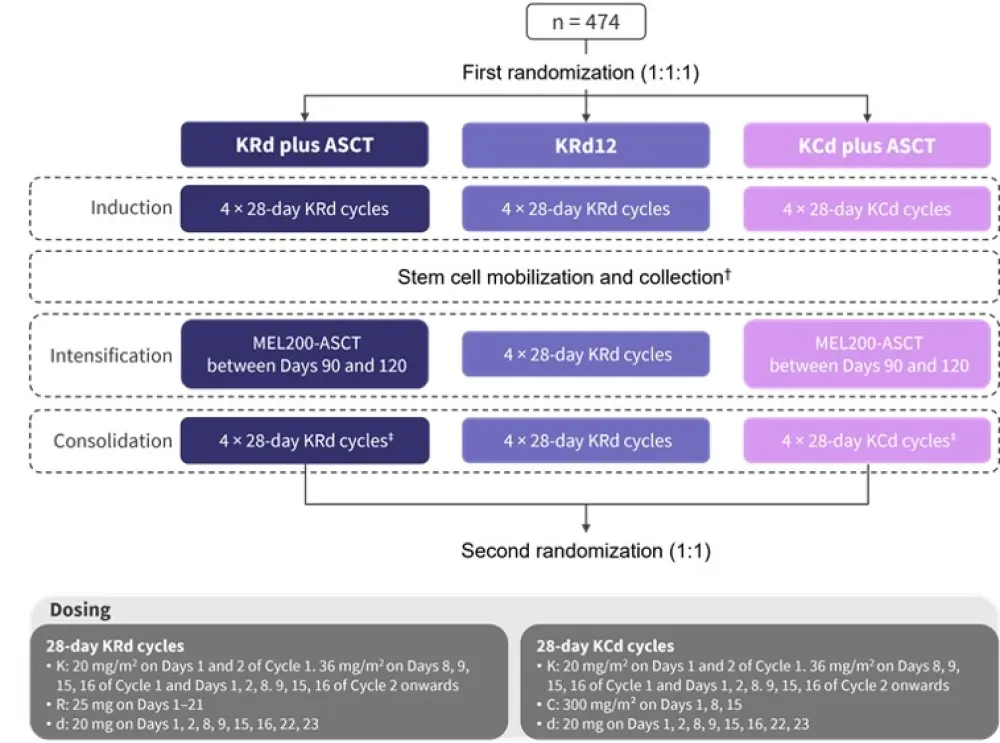

At enrolment, 474 patients were randomized (first randomization) into one of the three induction, intensification, consolidation groups, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. FORTE trial design of the first randomization

ASCT, autologous stem cell transplantation; C, cyclophosphamide; d, dexamethasone; K, carfilzomib; MEL200, 200 mg/m2 melphalan; R, lenalidomide; KRd12, 12 KRd cycles.

*Adapted from Gay et al.1

†Involving 2,000 mg/m² intravenous cyclophosphamide on Day 1 plus 10 µg/kg subcutaneous granulocyte-colony stimulating factor from Day 5 until stem cell collection was complete.

‡Within 90–120 days post ASCT.

Second randomization

Patients completing consolidation were randomized for a second time to maintenance treatment with either lenalidomide alone (10 mg on Days 1–21 every 28 days until progression or intolerance) or also with carfilzomib (36 mg/m² on Days 1, 2, 15, and 16 every 28 days).

This trial was revised on February 11, 2019, altering the carfilzomib dose and schedule to daily 70 mg/m² on Days 1 and 15 for up to 2 years, or lenalidomide monotherapy until progression or intolerance.

Results

On January 7, 2021 (data cutoff), 42% of patients had progressed or died, 60% of patients were receiving therapy with carfilzomib + lenalidomide (all of these patients had finished 2 years of carfilzomib and were receiving only lenalidomide), and 55% were receiving lenalidomide monotherapy.

The median duration of follow-up was 50.9 months (interquartile range, 45.7–55.3 months) from the first randomization and 37.3 months (interquartile range, 32.9–41.9 months) from the second randomization.

Primary endpoint outcomes

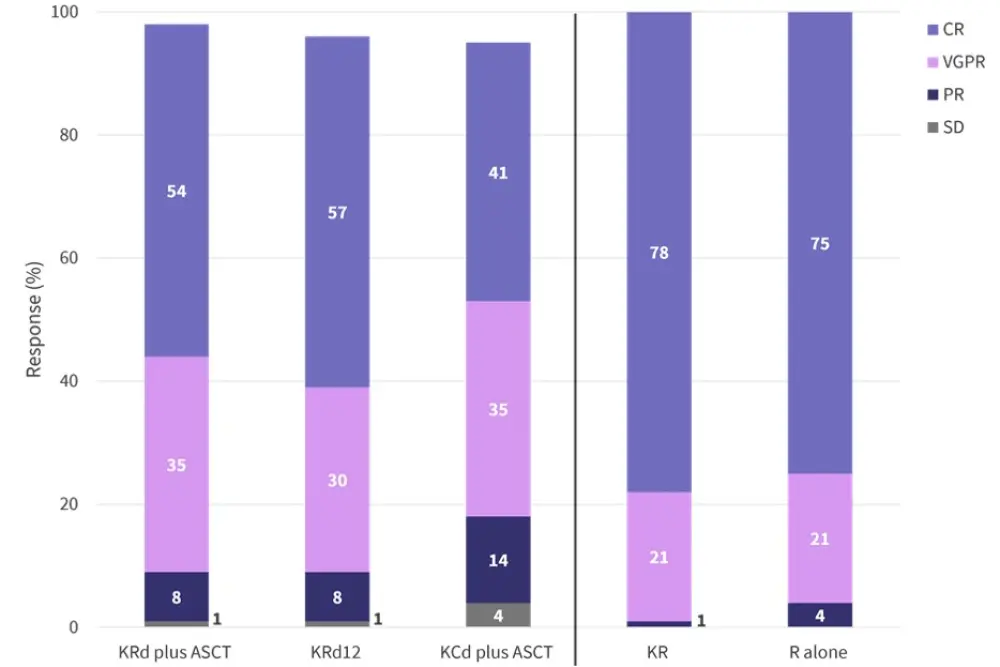

In the first part of the study, in the intention-to-treat population, 70% of patients receiving KRd and 53% of patients receiving KCd reached at least a very good partial response following induction (odds ratio, 2.14; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.44–3.19; p = 0.0002). Thus, the first primary endpoint of the FORTE trial was met. Figure 2 shows the response rates per arm throughout the study.

Subsequently, these patients were randomized to maintenance therapy with carfilzomib + lenalidomide (n = 178) or lenalidomide alone (n=178). The 3-year PFS from the second randomization was 75% in patients treated with carfilzomib + lenalidomide (95% CI, 68–82, median, not reached [NR]; 95% CI, NR–NR) versus 65% with lenalidomide alone (95% CI, 58–72, median, NR; 95% CI, NR–NR) (hazard ratio, 0.64; 95% CI ,0.44–0.94; p = 0.023). Despite the reported superiority of carfilzomib + lenalidomide maintenance, longer follow-up is needed to elucidate the impact of the induction therapy in the maintenance regimen efficacy.

Figure 2. Percentage of patients in the intention-to-treat population achieving disease stabilization or response to each induction regimen and maintenance therapy*

ASCT, autologous stem cell transplantation; CR, complete response including stringent complete response; KCd, carfilzomib + cyclophosphamide + dexamethasone; KR, carfilzomib + lenalidomide; KRd, carfilzomib + lenalidomide + dexamethasone; KRd12, 12 KRd cycles; PR, partial response; R, lenalidomide; SD, stable disease; VGPR, very good partial response.

*Data from Gay, et al.1

Secondary endpoints

Higher rates of stringent complete response, MRD negativity at 10−5 by multiparameter flow cytometry, and 1-year sustained MRD negativity were reported in the KRd plus ASCT arm. This advantage is also translated into a longer PFS, although as reported in other trials on NDMM, all patients who remain MRD negative after 1 year show an advantage in PFS regardless of the therapy. No significant differences in overall survival can be seen at the current follow-up. Table 2 shows the best response in the intention-to-treat population in the first and second part of the study.

Table 2. Best response in the intention-to-treat population*

|

ASCT, autologous stem cell transplantation; CR, complete response; KCd, carfilzomib + cyclophosphamide + dexamethasone; KR, carfilzomib + lenalidomide; KRd, carfilzomib + lenalidomide + dexamethasone; KRd12, 12 KRd cycles; MRD, minimal residual disease; PFS, progression-free survival; R, lenalidomide. |

|||||

|

Response, % |

Induction, intensification, and consolidation |

Maintenance |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

KRd plus ASCT |

KRd12 |

KCd plus ASCT |

KR |

R |

|

|

Stringent CR† |

46 |

44 |

32 |

68 |

65 |

|

MRD negativityठ|

62 |

56 |

43 |

81 |

79 |

|

1-year sustained MRD negativity§ |

47 |

35 |

25 |

— |

— |

|

4-year PFS |

69 |

56 |

51 |

— |

— |

|

4-year PFS in patients with MRD negativity§ |

83 |

63 |

69 |

— |

— |

|

4-year PFS in patients with 1-year sustained MRD negativity§ |

87 |

92 |

84 |

— |

— |

|

4-year overall survival |

86 |

85 |

76 |

— |

— |

|

3-year overall survival |

— |

— |

— |

94 |

90 |

Safety

During induction and consolidation, the most frequently reported Grade 3–4 adverse events (AEs) were neutropenia (13% of patients in the KRd plus ASCT group vs 10% in the KRd12 group vs 11% in the KCd plus ASCT group), dermatological toxicity (6% vs 8% vs 1%, respectively), and hepatic toxicity (8% vs 8% vs 0%, respectively).

Treatment-related serious AEs were observed in 11% of patients in the KRd-ASCT group, 19% in the KRd12 group, and 11% in the KCd plus ASCT group. A total of 35 patients discontinued treatment due to an AE, but they were distributed across induction arms. Most patients who experienced mobilization failure and discontinued treatment were in the KRd group.

During maintenance, the most common Grade 3–4 AEs were neutropenia (20% of patients in the carfilzomib + lenalidomide group vs 23% of patients in the lenalidomide alone group), infections (5% vs 7%, respectively), and vascular events (7% vs 1%, respectively). Rates of discontinuation due to AEs were similar across groups (12%). The investigators identified intravenous infusion and a higher frequency of cardiovascular events (including hypertension and thrombotic microangiopathy) as the main limitations for using carfilzomib in the maintenance setting at the defined doses.

Conclusion

In conclusion, patients with NDMM had a statistically and clinically meaningful benefit with KRd treatment followed by ASCT compared with KCd plus ASCT and KRd12. These findings again validate the crucial role of ASCT in the management of MM and support further evaluation of KRd versus standard of care in patients with NDMM who are eligible for transplant. Ongoing studies, such as the GMMG-CONCEPT trial (NCT03104842), combine KRd with an anti-CD38 monoclonal antibody and explore its efficacy in the high-risk population. In the transplant-eligible patient population, maintenance with carfilzomib + lenalidomide improved PFS and exhibited manageable toxicity compared with the standard of care, lenalidomide monotherapy, although a reduced dose of carfilzomib should be considered.

References

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statements:

The content was clear and easy to understand

The content addressed the learning objectives

The content was relevant to my practice

I will change my clinical practice as a result of this content

Your opinion matters

On average, how many patients with MGUS/smoldering MM do you see in a month?