All content on this site is intended for healthcare professionals only. By acknowledging this message and accessing the information on this website you are confirming that you are a Healthcare Professional. If you are a patient or carer, please visit the International Myeloma Foundation or HealthTree for Multiple Myeloma.

The mm Hub website uses a third-party service provided by Google that dynamically translates web content. Translations are machine generated, so may not be an exact or complete translation, and the mm Hub cannot guarantee the accuracy of translated content. The mm and its employees will not be liable for any direct, indirect, or consequential damages (even if foreseeable) resulting from use of the Google Translate feature. For further support with Google Translate, visit Google Translate Help.

The Multiple Myeloma Hub is an independent medical education platform, sponsored by Bristol Myers Squibb, GSK, Legend Biotech, Pfizer, and Roche. Funders are allowed no direct influence on our content. The levels of sponsorship listed are reflective of the amount of funding given. View funders.

Now you can support HCPs in making informed decisions for their patients

Your contribution helps us continuously deliver expertly curated content to HCPs worldwide. You will also have the opportunity to make a content suggestion for consideration and receive updates on the impact contributions are making to our content.

Find out more

Create an account and access these new features:

Bookmark content to read later

Select your specific areas of interest

View multiple myeloma content recommended for you

What is the clinical value of adding daratumumab to CyBorD in the treatment of light-chain amyloidosis? Results from phase III ANDROMEDA study

Systemic amyloid light-chain (AL) amyloidosis is a rare disease associated with delayed diagnosis and poor prognosis due to the involvement of multiple organ systems, particularly the cardiovascular system. It is characterized by the accumulation of insoluble amyloid fibrils produced by clonal CD38+ plasma cells in tissues and organs, and the death rate within the first year of diagnosis is around 30%. Even though agents used in the treatment of multiple myeloma (MM), mainly bortezomib, are able to improve outcomes, there is no approved therapy for AL amyloidosis. There is still an unmet need for more effective therapies to achieve rapid and deep hematologic responses that reverse organ dysfunction and improve outcomes.

Efstathios Kastritis and colleagues are investigating the efficacy and safety of adding subcutaneous (SC) daratumumab (DARA) to cyclophosphamide, bortezomib, and dexamethasone (CyBorD) compared with CyBorD alone in patients with newly diagnosed AL amyloidosis, in the phase III, randomized, open-label, active-controlled ANDROMEDA study. The primary results were presented by Kastritis during the Virtual Edition of the 25th European Hematology Association (EHA) Annual Congress.1

CyBorD is considered a standard of care for AL amyloidosis. DARA is a human CD38-targeted antibody approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the European Medicines Agency (EMA) for the treatment of MM. Previous studies have shown that DARA monotherapy demonstrated an acceptable safety profile in relapsed/refractory AL amyloidosis.2,3

Study design1

Patients were deemed eligible if they met the following criteria:

- Diagnosed with AL amyloidosis with ≥ 1 organ involvement

- Treatment-naïve for AL amyloidosis and MM

- Cardiac Stage I–IIIA (Mayo Clinic 2004 cardiac staging system)

- Estimated glomerular filtration rate of ≥ 20 mL/min

Stratification was based on cardiac stage, whether transplantation was offered, and the level of creatinine clearance (≥ 60 mL/min or < 60 mL/min). Randomization was 1:1 to receive either of the following arms in 28-day cycles during the treatment phase:

- DARA + CyBorD

- DARA SC 1,800 mg every week for Cycles 1 and 2, every 2 weeks for Cycles 3–6, plus

- CyBorD: Dexamethasone 40 mg intravenous (IV) or oral, followed by cyclophosphamide 300 mg/m2 IV or oral, followed by bortezomib 1.3 mg/m2 SC on Days 1, 8, 15, and 22 in every cycle for a maximum six cycles, followed by

- DARA SC 1,800 mg every 4 weeks until major organ deterioration (MOD) progression-free survival (PFS) or a total of 24 cycles

- CyBorD for six cycles, as above

Patients were observed every 4 weeks for the first six cycles and every 8 weeks thereafter until MOD, death, end of study, or withdrawal.

- Primary endpoint: Overall hematologic complete response (CR) rate in intent-to-treat population

- Secondary endpoints: MOD-PFS, organ response rate, time to hematologic response, overall survival, safety

Patient characteristics1

After the positive results from the safety run-in with 28 patients, a total of 388 additional patients were randomized (n = 195 in DARA + CyBorD arm; n = 193 in CyBorD alone arm). Baseline characteristics and demographics were similar between treatment arms (see Table 1).

ECOG performance status was similar: most patients had a score of 0 or 1, and a median of two organs were involved in both arms. Organ involvement was also similar across treatment arms. Approximately 35% of patients had Stage III cardiac disease, suggestive of advanced cardiac amyloidosis.

Table 1. Patient characteristics among two arms1

|

CyBorD, cyclophosphamide + bortezomib + dexamethasone; DARA, daratumumab; dFLC, difference between involved and uninvolved free light chains |

||

|

Characteristic |

DARA + CyBorD |

CyBorD |

|

Median age, years (range) |

62 (34–87) |

64 (35–86) |

|

Median time from diagnosis, days (range) |

48 (8–1,611) |

43 (5–1,102) |

|

Median baseline dFLC, mg/L (range) |

200 (2–4,749) |

186 (1–9,983) |

|

Organ involvement, % |

|

|

|

≥ 2 organs |

66 |

65 |

|

Heart |

72 |

71 |

|

Kidney |

59 |

59 |

|

Cardiac stage, % |

|

|

|

I |

24 |

22 |

|

II |

39 |

42 |

|

IIIA |

36 |

33 |

|

IIIB |

1 |

3 |

|

Renal stage, % (n = 193 in both arms) |

|

|

|

I |

55 |

52 |

|

II |

35 |

38 |

|

III |

10 |

9 |

Results1

The median duration of follow-up was 11.4 months (range, 0.03–21.3). Key findings related to treatment exposure are shown in Table 2, below.

In the safety population,

- Median duration of treatment was 9.6 months in DARA-CyBorD arm and 5.3 months in CyBorD arm

- Similar death rate was seen among DARA-CyBorD and CyBorD arms

- In the DARA-CyBorD arm, 77% of patients continued to receive DARA SC monotherapy beyond six cycles

In the intent-to-treat population,

- Rate of discontinuation was higher in CyBordD arm (36%), although discontinuation rate (due to adverse events or other reasons, including physician decision and patient withdrawal) were similar between arms

- More patients had progressive disease in the CyBorD arm (6% vs 1% in the DARA-CyBorD arm)

- In the CyBorD arm, 42% of patients required subsequent therapy compared with 10% in the DARA-CyBorD arm

Table 2. Key findings from safety population and ITT population1

|

AE, adverse event; auto-SCT, autologous stem cell transplantation; CyBorD, cyclophosphamide + bortezomib + dexamethasone; DARA, daratumumab; ITT, intent to treat; IV, intravenous |

||

|

Safety population (≥ 1 dose of study treatment) |

DARA-CyBorD (n = 193) |

CyBorD (n = 188) |

|

Median duration of treatment, months (range) |

9.6 (0.03–21.2) |

5.3 (0.03–7.3) |

|

Deaths, n (%) |

27 (14) |

29 (15) |

|

Maintenance therapy with DARA SC monotherapy, (%)

|

77 |

— |

|

ITT population |

DARA-CyBorD (n = 195) |

CyBorD (n = 193) |

|

Treatment discontinuation, % Death In need of auto-SCT AE Subsequent therapy Progressive disease |

27 10 6 4 3 1 |

36 7 2 4 12 6 |

|

Any subsequent therapy, n (%) ASCT, n DARA IV monotherapy/combination, n |

19 (10) 13 0 |

79 (42) 20 48 |

Efficacy1

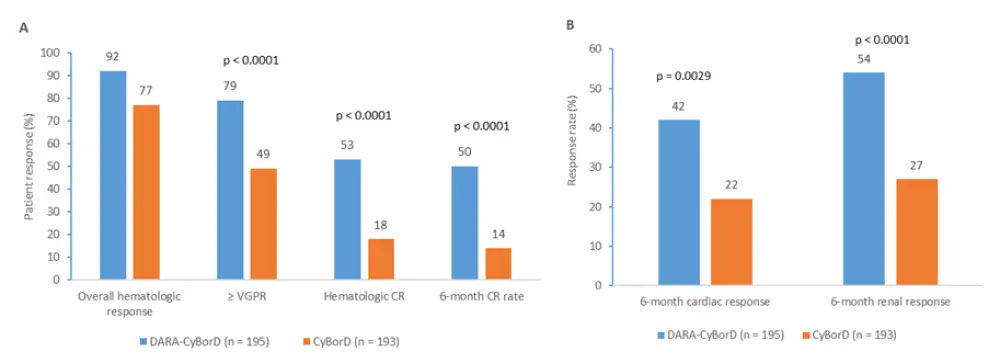

- Significantly higher hematologic response rates with DARA-CyBorD vs CyBorD (see Figure 1)

-

- Best response of hematologic CR (odds ratio [OR], 5.1; 95% CI, 3.2–8.2; p < 0.0001)

- 6-month CR rate (OR, 6.1; p < 0.0001)

- Very good partial response rates (VGPR) (OR, 3.8; p < 0.0001)

- Among responders, median time to CR and VGPR was shorter with DARA-CyBorD vs CyBorD (60 days and 17 days vs 85 days and 25 days, respectively)

- The benefit of DARA-CyBorD was observed across all subgroups in terms of higher hematologic CR rates

- DARA-CyBorD significantly delayed MOD, disease progression, or death (hazard ratio [HR], 0.58; 95% CI, 0.37–0.93; p = 0.0230) and increased MOD event-free survival (HR, 0.40; 95% CI, 0.28–0.57; p < 0.0001)

- Six-month cardiac and renal responses were also significantly higher with DARA-CyBorD vs CyBorD (42% vs 22%, p = 0.0029 and 54% vs 27%, p < 0.0001, respectively)

- Median time to next treatment was 10.4 months in CyBorD, while it was not reached for DARA-CyBorD at the time of analysis

- At the time of analysis, overall survival data were not mature

Figure 1. Patient outcomes in both arms1

A Patient response rates and B organ responses at Month 6 in patients who received DARA-CyBorD combination, and patients who received CyBorD.

CR, complete response; CyBorD, cyclophosphamide + bortezomib + dexamethasone; DARA, daratumumab; VGPR, very good partial response

Safety1

DARA-CyBorD has shown a similar safety profile to the established profiles of DARA SC and CyBorD. The number of patients experiencing a treatment-emergent adverse event (TEAE) was similar among both arms (59 in the DARA-CyBorD arm and 57 in the CyBorD arm). The number of death events were also similar (n = 27 in the DARA-CyBorD arm; n = 29 in the CyBorD arm). The key results of the safety analysis are presented in Table 3, below.

Table 3. The most common Grade ≥ 3 TEAEs (≥ 5% of patients)1

|

CyBorD, cyclophosphamide + bortezomib + dexamethasone; DARA, daratumumab; TEAE, treatment-emergent adverse event |

||

|

TEAE, % |

DARA-CyBorD (n = 193) |

CyBorD (n = 188) |

|

Serious TEAEs, any Grade |

43 |

36 |

|

Lymphopenia |

13 |

10 |

|

Pneumonia |

8 |

4 |

|

Cardiac failure |

6 |

5 |

|

Diarrhea |

6 |

4 |

|

Neutropenia |

5 |

3 |

|

Syncope |

5 |

6 |

|

Anemia |

4 |

5 |

|

Peripheral edema |

3 |

6 |

- Infection rate was slightly higher in the DARA-CyBorD arm (12% vs 9% in the CyBorD arm)

- During the first 6 months, 25 and 20 death events were seen in the DARA-CyBorD and CyBorD arms, respectively; most events were related to underlying AL amyloidosis

- Discontinuation rate due to TEAEs was 4% in both arms

- Systemic administration-related and injection-site reactions with DARA-CyBorD were 7% and 11%, respectively; all were Grade 1–2 and occurred during the first administration

Conclusion

In AL amyloidosis, rapid hematologic response is critical to reverse organ deterioration, and it is a strong predictor of improved overall survival along with subsequent response. Adding DARA SC to CyBorD is associated with significantly higher and deeper hematological response rates, and improvements in clinical outcomes include delayed MOD-PFS, improved MOD event-free survival, and organ response in the treatment of patients with newly diagnosed AL amyloidosis. The safety profile is acceptable, and DARA in combination with CyBorD may provide a new option for this patient population.

References

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statements:

The content was clear and easy to understand

The content addressed the learning objectives

The content was relevant to my practice

I will change my clinical practice as a result of this content

Your opinion matters

On average, how many patients with MGUS/smoldering MM do you see in a month?