All content on this site is intended for healthcare professionals only. By acknowledging this message and accessing the information on this website you are confirming that you are a Healthcare Professional. If you are a patient or carer, please visit the International Myeloma Foundation or HealthTree for Multiple Myeloma.

The mm Hub website uses a third-party service provided by Google that dynamically translates web content. Translations are machine generated, so may not be an exact or complete translation, and the mm Hub cannot guarantee the accuracy of translated content. The mm and its employees will not be liable for any direct, indirect, or consequential damages (even if foreseeable) resulting from use of the Google Translate feature. For further support with Google Translate, visit Google Translate Help.

The Multiple Myeloma Hub is an independent medical education platform, sponsored by Bristol Myers Squibb, GSK, Legend Biotech, Pfizer, and Roche. Funders are allowed no direct influence on our content. The levels of sponsorship listed are reflective of the amount of funding given. View funders.

Now you can support HCPs in making informed decisions for their patients

Your contribution helps us continuously deliver expertly curated content to HCPs worldwide. You will also have the opportunity to make a content suggestion for consideration and receive updates on the impact contributions are making to our content.

Find out more

Create an account and access these new features:

Bookmark content to read later

Select your specific areas of interest

View multiple myeloma content recommended for you

Teclistamab for relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma: Updated phase I/II MajesTEC-1 results

Despite ongoing advancements in the treatment of multiple myeloma (MM), the disease is still largely incurable, with a significant proportion of patients relapsing and developing refractoriness to previous therapies. Standard treatments include proteasome inhibitors (PIs), immunomodulatory drugs (IMiDs), and/or anti-CD38 monoclonal antibodies (mAbs).1 Patients who progress following these treatments have limited therapeutic options, and their outcomes are generally poor.1 Therefore, therapies are currently being developed and optimized to improve survival outcomes of patients with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma (RRMM), such as B-cell maturation antigen (BCMA)-targeting immunotherapies, including antibody–drug conjugates (ADCs), chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy (CAR-T), and bispecific antibodies.1

Teclistamab (JNJ-64007957) is a humanized bispecific antibody that targets both CD3 expressed on the surface of T cells and BCMA expressed on the surface of myeloma cells to induce T cell-mediated cytotoxicity of BCMA-expressing myeloma cells.1 Teclistamab’s efficacy and safety data available to date have been reported from the multicohort MajesTEC-1 phase I/II trials (NCT03145181 and NCT04557098), and in the TRIMM-2 phase Ib study (NCT04108195) in combination with daratumumab. The results from Cohort A of the MajesTEC-1 trial were recently published in The New England Journal of Medicine by Philippe Moreau et al.1 The latest results from Cohort C of the MajesTEC-1 trial, including patients who had previously been exposed to BCMA-targeted treatment, were recently presented at the European Hematology Association (EHA)2022 Congress by Cyrille Touzeau.2 Below we summarize the key findings from these studies.

Based on these results, on July 22, 2022, the Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) of the European Medicines Agency (EMA) recommended conditional marketing authorization for teclistamab monotherapy for patients with RRMM who have been previously treated at least once with an IMiD, PI, and anti-CD38 antibody.3

Study design and patient characteristics

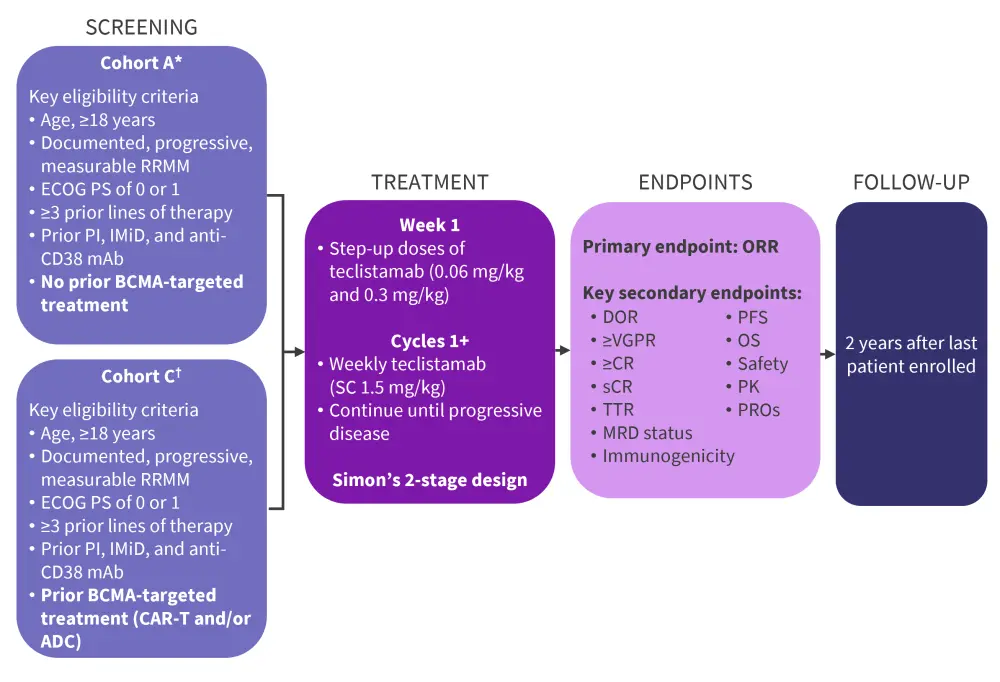

MajesTEC-1 is an open-label, multi-cohort, multi-center phase I/II study evaluating the efficacy and safety of teclistamab in patients with RRMM.2 This pivotal trial supports the FDA biologics license application of teclistamab, which was presented in December 2021 and is still under review.3

Cohort A included a total of 165 patients with RRMM who were enrolled to receive teclistamab; 40 were enrolled in phase I and 125 in phase II.1 Included participants had received at least three prior lines of therapy, with no exposure to prior anti-BCMA treatment. The median age of all patients was 64 years and the median time between diagnosis and the first dose was 6 years. Among these patients, 77.6% had triple-class refractory disease and had received a median five previous lines of therapy.1

Cohort C included a total of 40 patients with RRMM who had previously been treated with ≥3 prior lines of therapy, including prior anti-BCMA treatment (CAR-T and/or ADC).2 The median age of the patients was 63.5 years and the median time between diagnosis and the first dose was 6.5 years.2

Study design and patient characteristics are detailed in Figure 1 and Table 1, respectively.

Figure 1. Study design*†

ADC, antibody–drug conjugate; BCMA, B-cell maturation antigen; CAR-T, chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy; CR, complete response; DOR, duration of response; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; IMiD, immunomodulatory drug; mAb, monoclonal antibody; MRD, minimal residual disease; ORR, overall response rate; OS, overall survival; PFS, progression-free survival; PI, proteasome inhibitor; PK, pharmacokinetics; PROs, patient-reported outcomes; RRMM, relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma; SC, subcutaneous; sCR, stringent complete response; TTR, time to response; VGPR, very good partial response.

*Data from Moreau, et al.1 and Touzeau.2

Table 1. Baseline characteristics

|

ADC, antibody–drug conjugate; BCMA, B-cell maturation antigen; CAR-T, chimeric antigen receptor T cell; ISS, International Staging System; IMiD, immunomodulatory drug; NR, not reported; PI, proteasome inhibitor. *Data from Moreau, et al.1 |

|||

|

Characteristic, % (unless otherwise stated) |

Cohort A |

Cohort A |

Cohort C |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Median age (range), years |

64.0 |

64.0 |

63.5 |

|

Sex |

|

|

|

|

Female |

44.0 |

41.8 |

NR |

|

Male |

56.0 |

58.2 |

62.5 |

|

Median time since diagnosis (range), years |

6.2 |

6.0 |

6.5 |

|

Extramedullary plasmacytomas ≥1‡ |

16.0 |

17.0 |

30.0 |

|

Bone marrow plasma cells ≥60% |

12.3 |

11.2 |

10.0 |

|

ISS stage§ |

|

|

|

|

I |

49.6 |

52.5 |

52.5 |

|

II |

37.4 |

35.2 |

22.5 |

|

III |

13.0 |

12.3 |

25.0 |

|

High-risk cytogenetics‖ |

— |

— |

33.3 |

|

del(17p) |

12.6 |

15.5 |

— |

|

t(4:14) |

10.8 |

10.8 |

— |

|

t(14:16) |

2.7 |

2.7 |

— |

|

Median prior lines of therapy (range) |

5 (2–14) |

5 (2–14) |

6 (3–14) |

|

Prior stem cell transplantation |

80.8 |

81.8 |

90.0 |

|

Prior therapy exposure |

|

|

|

|

Triple class¶ |

100 |

100 |

100 |

|

Penta class# |

72.0 |

70.3 |

80.0 |

|

BCMA-targeted treatment |

— |

— |

100 |

|

ADC |

— |

— |

72.5 |

|

CAR-T |

— |

— |

37.5 |

|

Refractory status |

|

|

|

|

Triple class¶ |

76.8 |

77.6 |

85.0 |

|

Penta drug# |

27.2 |

30.3 |

35.0 |

|

Refractory to last line therapy |

92.0 |

89.7 |

85.0 |

Results

Efficacy

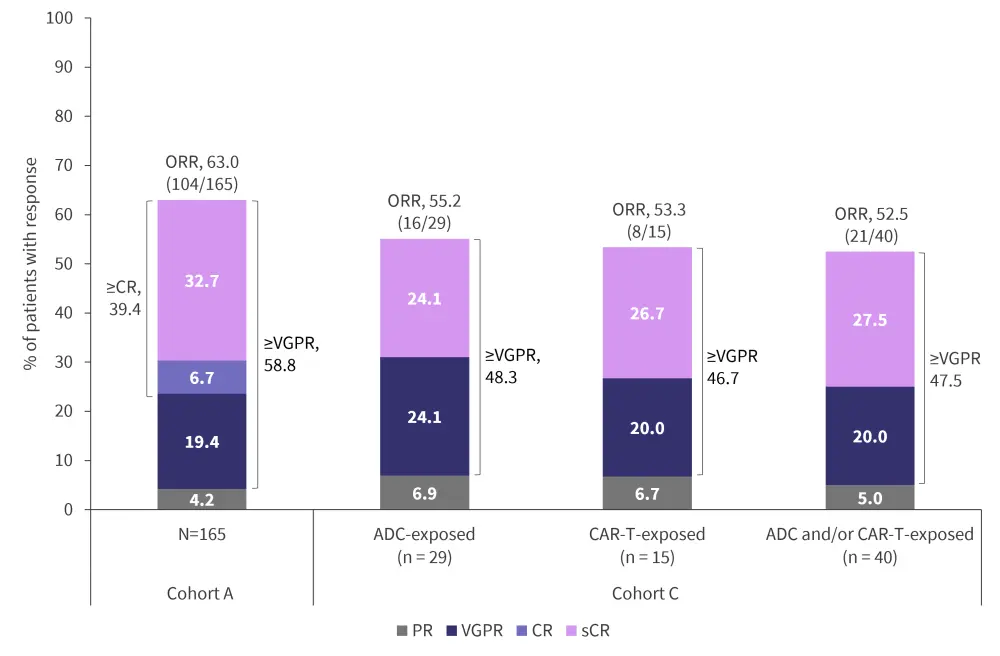

In Cohort A, the overall response rate (ORR) was 63.0%, with a median follow-up of 14.1 months, and 39.4% of patients achieved at least a complete response.1 In Cohort C, the ORR was 52.5% in patients with prior exposure to ADC and/or CAR-T, with a median follow-up of 12.5 months.2 Of note, 71.4% of responders maintained their response after a median of 11.8 months.2 Detailed response rates and outcomes are shown in Figure 2 and Table 2.

Figure 2. Response rates in patients from Cohorts A* and C†‡

ADC, antibody–drug conjugate; CAR-T, chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy; CR, complete response; ORR, overall response rate; PR, partial response; sCR, stringent complete response; VGPR, very good partial response.

*Data from Moreau, et al.1

†Data from Touzeau.2

‡PR or better as per the International Myeloma Working Group 2016 criteria.

Safety

All patients in Cohort A reported having an adverse event (AE), of which 94.5% of them were Grade 3 or 4, and two patients discontinued teclistamab treatment due to AEs.1 In Cohort C, teclistamab was well tolerated with no dose reductions or discontinuations due to AEs.2 Infections occurred in 76.4% of patients in Cohort A, among which 44.8% were Grade 3/4,1 and in 65.0% of patients in Cohort C, of which 30.0% were Grade 3/4.2 As shown in Table 3, the most common AEs were cytokine release syndrome (CRS; Cohort A, 72.1%; Cohort C, 65.0%) and hematologic, including neutropenia (Cohort A, 70.9%; Cohort C, 67.5%) and anemia (Cohort A, 52.1%; Cohort C, 50.0%).1,2 In Cohort A, there were 19 deaths due to AEs, including 12 from COVID-19 infection.1 In Cohort C, there were six deaths due to AEs, including one death due to cardiac arrest (teclistamab-related) and two from COVID-19 infection.2

Most and all CRS events were Grade 1/2 in Cohorts A and C, respectively, which were fully resolved without teclistamab treatment discontinuation.1,2 Both median time to onset and median duration of CRS was 2 days in Cohort A.1 Most CRS events in Cohort A occurred after step-up and Cycle 1 doses.1

Neurotoxic events occurred in 14.5% of patients in Cohort A and 25.0% of patients in Cohort C, and the most common neurotoxic events were headache (Cohort A, 8.5%; Cohort C, 12.5%) and immune effector cell-associated neurotoxicity syndrome (Cohort A, 3.0%; Cohort C, 10.0%).1,2

Table 3. AEs of special interest and AEs occurring in ≥20% of patients in Cohort A* and Cohort C†

|

AE, adverse event. |

||||

|

AE, % |

Cohort A* |

Cohort C† |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Any Grade |

Grade 3/4 |

Any Grade |

Grade 3/4 |

|

|

Any AE |

100 |

94.5 |

— |

— |

|

Hematologic |

|

|

|

|

|

Neutropenia |

70.9 |

64.2 |

67.5 |

62.5 |

|

Anemia |

52.1 |

37.0 |

50.0 |

35.0 |

|

Thrombocytopenia |

40.0 |

21.2 |

45.0 |

30.0 |

|

Lymphopenia |

34.5 |

32.7 |

45.0 |

42.5 |

|

Nonhematologic |

|

|

|

|

|

Diarrhea |

28.5 |

3.6 |

35.0 |

2.5 |

|

Fatigue |

27.9 |

2.4 |

— |

— |

|

Nausea |

27.3 |

0.6 |

— |

— |

|

Injection site erythema |

26.1 |

0 |

32.5 |

0 |

|

Pyrexia |

27.3 |

0.6 |

32.5 |

0 |

|

Headache |

23.6 |

0.6 |

22.5 |

0 |

|

Arthralgia |

21.8 |

0.6 |

25.0 |

0 |

|

Constipation |

20.6 |

0 |

35.0 |

0 |

|

Cough |

20.0 |

0 |

— |

— |

|

Pneumonia |

18.2 |

12.7 |

— |

— |

|

Covid-19 |

17.6 |

12.1 |

— |

— |

|

Bone pain |

17.6 |

3.6 |

20.0 |

2.5 |

|

Dyspnea |

— |

— |

22.5 |

2.5 |

|

Asthenia |

— |

— |

20.0 |

5.0 |

|

Cytokine release syndrome |

72.1 |

0.6 |

65.0 |

0 |

|

Neurotoxic event |

14.5 |

0.6 |

— |

— |

Biomarkers

Serum levels of soluble BCMA were evaluated as a potential biomarker of tumor burden and response. In Cohort A, Moreau et al.1 reported rapid decreases in the total level of soluble BCMA in 68% of 59 evaluable patients who had at least a partial response in the first month of teclistamab treatment. By contrast, 96% of 28 patients without a response to teclistamab during Cycle 1 had increased soluble BCMA levels. Further, reductions in soluble BCMA were greater in patients with a deeper response. Touzeau2 highlighted that baseline BCMA expression and soluble BCMA levels were comparable in patients with (Cohort C) and without (Cohort A) prior anti-BCMA treatment.

Conclusion

Here, we summarized the most recent data from the multi-cohort phase I/II MajesTEC-1 trial. In Cohort A, Moreau et al.1 highlighted the deep and durable responses following teclistamab treatment in patients with RRMM who had previously been heavily treated with PIs, IMiDs, and anti‑CD38 mAbs, and had no prior exposure to anti-BCMA treatment. Touzeau2 presented promising data on the efficacy and safety of teclistamab in patients with RRMM who were also triple-class exposed but had previously received other BCMA-targeted treatment (Cohort C). Preliminary results demonstrated promising ORRs, with early responses that deepened over time, and a well-tolerated safety profile, with low grade and manageable AEs. Therefore, both Moreau et al.1 and Touzeau2 feel that teclistamab has the potential to provide substantial clinical benefit to a broad population of patients with RRMM and suggest that the subcutaneous administration and the lower-grade profile of CRS may support outpatient administration of teclistamab.

References

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statements:

The content was clear and easy to understand

The content addressed the learning objectives

The content was relevant to my practice

I will change my clinical practice as a result of this content

Your opinion matters

On average, how many patients with MGUS/smoldering MM do you see in a month?