All content on this site is intended for healthcare professionals only. By acknowledging this message and accessing the information on this website you are confirming that you are a Healthcare Professional. If you are a patient or carer, please visit the International Myeloma Foundation or HealthTree for Multiple Myeloma.

The mm Hub website uses a third-party service provided by Google that dynamically translates web content. Translations are machine generated, so may not be an exact or complete translation, and the mm Hub cannot guarantee the accuracy of translated content. The mm and its employees will not be liable for any direct, indirect, or consequential damages (even if foreseeable) resulting from use of the Google Translate feature. For further support with Google Translate, visit Google Translate Help.

The Multiple Myeloma Hub is an independent medical education platform, sponsored by Bristol Myers Squibb, GSK, Legend Biotech, Pfizer, and Roche. Funders are allowed no direct influence on our content. The levels of sponsorship listed are reflective of the amount of funding given. View funders.

Now you can support HCPs in making informed decisions for their patients

Your contribution helps us continuously deliver expertly curated content to HCPs worldwide. You will also have the opportunity to make a content suggestion for consideration and receive updates on the impact contributions are making to our content.

Find out more

Create an account and access these new features:

Bookmark content to read later

Select your specific areas of interest

View multiple myeloma content recommended for you

Recommendations for transplantation in MM from the American Society for Transplantation and Cellular Therapy

Do you know... Which of the following does the ASTCT not recommend for transplantation in the non-clinical trial front-line setting in multiple myeloma?

The treatment landscape for multiple myeloma (MM) has changed significantly with the advent of many novel therapeutic agents; however, the role of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) remains crucial.1 Autologous HSCT (auto-HSCT) has been the standard treatment for eligible patients for the past 20 years, with a good body of evidence supporting its benefits. However, there remains uncertainty around the timing of upfront auto-HSCT and the role of post auto-HSCT consolidation/maintenance therapy. In addition, the role of allogeneic HSCT (allo-HSCT) in the treatment of MM remains debatable, with inconsistent results across clinical trials. Currently, there is wide variation in the clinical practice around choosing different treatment modalities for MM, warranting recommendations to address these areas of clinical uncertainty.1

The American Society of Transplantation and Cellular Therapy’s (ASTCT) Committee on Practice Guidelines convened an expert panel to formulate recommendations for transplantation and cellular therapies in patients with MM. Binod Dhakal et al.1 recently published these recommendations in Transplantation and Cellular Therapy and here we summarize the clinical practice recommendations relating to transplantation.

Methodology

The RAND-modified Delphi-method was used to generate consensus statements to address the role of HSCT in patients with newly diagnosed MM (NDMM) and relapsed/refractory (R/R) MM. The panel comprised transplant and cell therapy physicians and non-cell therapy physicians from both teaching and community-based settings (Table 1).

Table 1. Characteristics of panelists*

|

allo-HSCT, allogeneic HSCT; auto-HSCT, autologous HSCT; CAR, chimeric antigen receptor; HSCT, hematopoietic stem cell transplantation; MM, multiple myeloma. |

|

|

Characteristics, % |

N = 35 |

|---|---|

|

Sex |

|

|

Male |

66 |

|

Female |

34 |

|

Practice setting |

|

|

Academic |

89 |

|

Community |

11 |

|

Type of clinical practice |

|

|

Non-transplant myeloma |

3 |

|

Primarily HSCT or cell therapy |

6 |

|

Combined myeloma and HSCT/cell therapy |

91 |

|

Region of practice |

|

|

North America |

60 |

|

Europe |

17 |

|

Asia |

17 |

|

Australia |

6 |

|

Years of clinical experience in MM or HSCT practice |

|

|

>10 |

60 |

|

6–10 |

31 |

|

≤5 |

9 |

|

>40 patients with MM seen by the individual member annually |

94 |

|

>300 annual transplants at respective programs (auto-HSCT + allo-HSCT) |

29 |

|

>250 annual auto-HSCTs performed at respective centers |

11 |

|

>200 annual auto-HSCTs performed at respective centers for myeloma |

11 |

|

>20 annual CAR T-cell therapies performed at respective centers for myeloma (on or off clinical trial) |

23 |

|

>20 allo-HSCTs performed at respective centers for myeloma |

0 |

Results

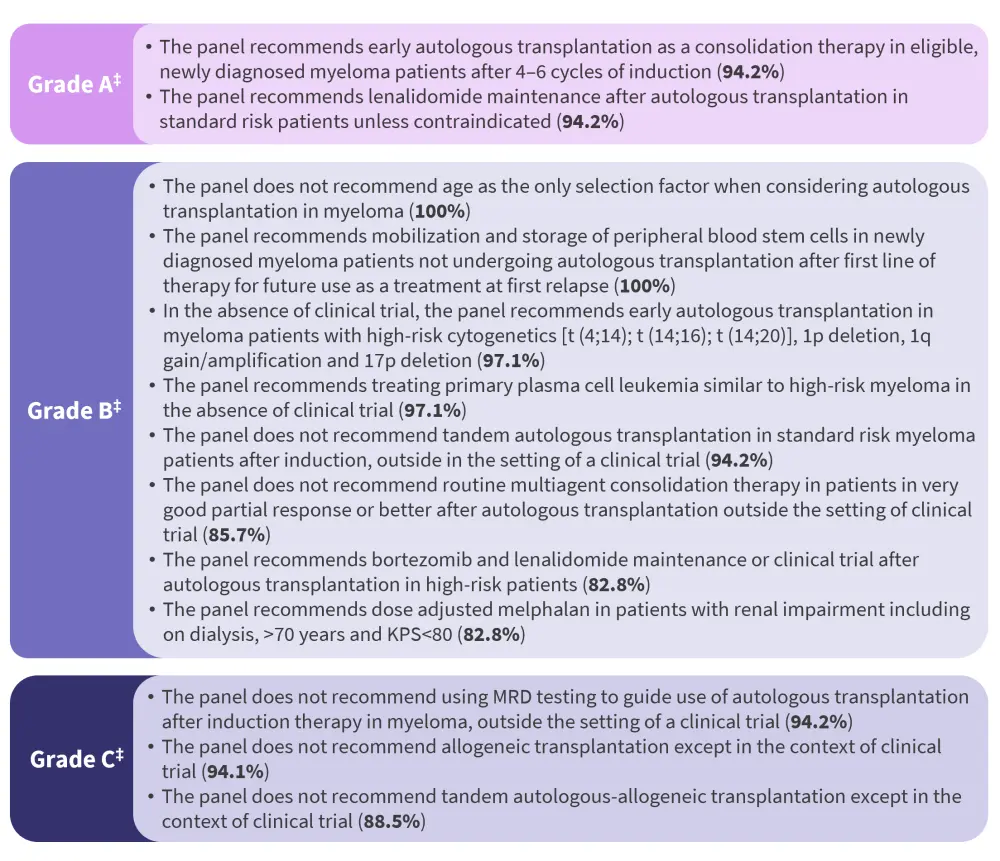

A total of 35 panelists participated with 100% response rates. In total, 12 consensus statements were recommended for transplantation in the front-line setting for patients with NDMM and one statement was recommended for plasma cell leukemia (PCL) (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Consensus statements for transplantation in the front-line setting in multiple myeloma*†

KPS, Karnofsky performance status; MRD, minimal residual disease.

*Adapted from Dhakal, et al.1

†For each grade, the recommendations are listed in descending order based on the level of agreement amongst panelists, as displayed in the brackets.

‡Based on the strength and level of supporting evidence, according to the Agency of Healthcare Research and Quality grading.

Front-line setting

Upfront auto-HSCT

Auto-HSCT has demonstrated both a progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) benefit in several clinical trials, which supports the recommendation for early auto-HSCT as a consolidation therapy in eligible patients with NDMM following 4–6 cycles of induction therapy, especially for those with high-risk cytogenetics after initial induction. The panel acknowledged that in select patients, delayed auto-HSCT might be a reasonable option based on the Intergroupe Francophone du Myélome (IFM) 2009 study. This study demonstrated a similar OS between patients receiving upfront and delayed auto-HSCT, at a median follow-up of 44 months and 93 months, respectively; however, early auto-HSCT was associated with higher minimal residual disease (MRD) negativity rates and a superior PFS benefit. Therefore, oncologists and patients should have a shared discussion on a delayed auto-HSCT approach. Continued improvement in PFS with frontline approaches may delay the first relapse and potential transplant such that it may no longer be a consideration due to age and other comorbidities. As MRD emerges as an important prognostic marker, MRD status may be used in the future to guide the timing of auto-HSCT for both standard- and high-risk patients and its role in the context of anti-CD38 antibodies therapies upfront should be defined.

The panel recommended against using only age as a selection criterion for auto-HSCT due to the lack of any pivotal randomized trials including patients ≥70 years of age. Performance status and frailty index should be incorporated when considering eligibility for auto-HSCT.

Consideration of dose-adjusted melphalan is an important decision point, with studies suggesting a safety profile at 200 mg/m2 of melphalan in patients with renal impairment and an age >70 years. Therefore, consideration of Karnofsky performance status, frailty, and clinical judgement were recommended when adjusting the melphalan dose.

Post-auto-HSCT (tandem auto-HSCT/consolidation)

Based on the results of two large randomized studies, which showed no benefit of tandem auto-HSCT in patients with standard-risk cytogenetics, the panel recommended against the use of auto-HSCT in this population. However, the findings were conflicting in the EMN02/HO95 (NCT01208766) and STaMINA (NCT01109004) trials, which included patients with high-risk cytogenetics. The contribution of standard consolidation to the outcomes of patients with NDMM is unknown; therefore, routine multiagent consolidation therapy in patients with a very good partial response or better was not recommended.

Post-auto-HSCT (maintenance)

Since the ideal duration of lenalidomide maintenance is not yet known, the panel recommended that cost, toxicities, and monitoring for therapy-related second malignancies should be considered in the discussion in the context of indefinite maintenance therapy. Several studies have demonstrated the safety and efficacy of proteasome inhibitor and immunomodulator (IMiD) maintenance in patients with high-risk cytogenetics. However, there is a lack of evidence on the efficacy of an ImiD/proteasome inhibitor combination compared with maintenance with IMiD monotherapy.

Upfront allo-HSCT (including tandem auto-allo-HSCT)

The panel recommended against the use of allo-HSCT in patients with MM, except in clinical trial settings in select young high-risk patients. Of note, the BMT CTN 1301 trial (NCT02440464), which investigated ixazomib maintenance after allo-HSCT in high-risk patients, closed prematurely, with an 11% treatment-related mortality among all allo-HSCT recipients.

Primary plasma cell leukemia

Two retrospective studies from the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research (CIBMTR) showed no significant benefit of allo-HSCT compared with auto-HSCT for PCL, which supported the recommendation that patients with primary PCL should be treated similar to patients with high-risk MM, while the need for novel clinical trials was acknowledged.

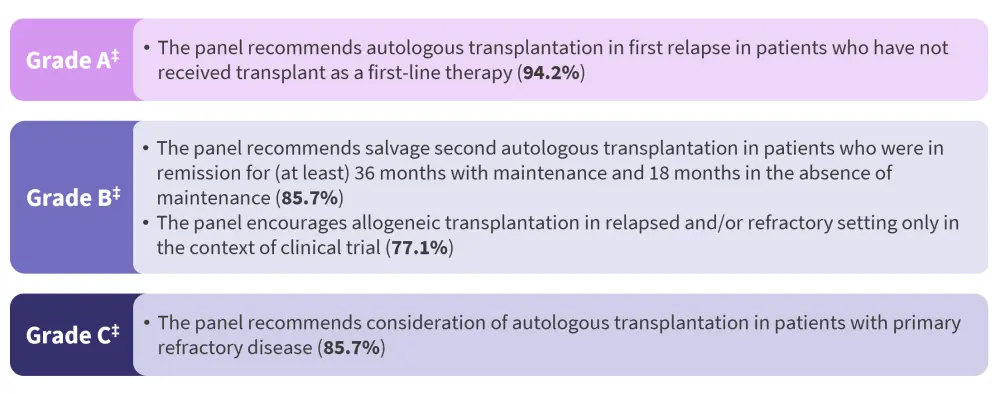

Relapsed/refractory setting

The panel made recommendations and issued guidance (Figure 2) for transplantation in the R/R setting in the context of the constantly changing treatment landscape and the availability of new drugs and combinations.

Figure 2. Consensus statements for transplantation for relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma*†

*Adapted from Dhakal, et al.1

†For each grade, the recommendations are listed in descending order based on the level of agreement amongst panelists, as displayed in the brackets.

‡Based on the strength and level of supporting evidence, according to the Agency of Healthcare Research and Quality grading.

Auto-HSCT for relapsed disease

The recommendation for auto-HSCT at first relapse in patients who did not receive it as part of their first-line therapy was based on the IFM study. In this study, the 79% of patients who received transplant at first relapse showed a survival benefit that was similar to that observed in the group of patients who received transplant upfront.

Auto-HSCT for primary refractory disease

Retrospective studies suggest that patients with primary refractory disease (less than a partial response to frontline therapy) may benefit from auto-HSCT, although these were conducted before current novel agents were available. Additional or intensified therapy may improve the depth of response pretransplantation, but it may not translate into survival benefit. This panel recommended to consider auto-HCT in patients with primary refractory disease. However, these population might benefit the most from participating in a clinical trials or receive alternative induction therapy.

Salvage auto-HSCT

There is lack of randomized data comparing second auto-HSCT to novel regimens, and with the emergence of chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapies and bispecific antigens, its use may decline. However, in settings with limited access to novel therapies, second auto-HSCT may be a cost-effective alternative as a bridging therapy in patients with rapidly progressive myeloma and severe cytopenias.

Allo-HSCT in R/R MM

Retrospective studies and one prospective study suggest that allo-HSCT has lower relapse rates in the salvage setting. However, allo-HSCT showed an inferior survival benefit compared with other modalities, such as second auto-HSCT, likely due to higher non-relapse mortality.

Conclusion

The expert panel discussion used an established, formal, reproducible, and systematic process of RAND-modified Delphi to formulate clinical practice recommendations and associated guidance for managing patients with both NDMM and R/R MM. These clinical practice recommendations, derived from both academic and community practitioners, provide a much-needed tool in the management of patients with NDMM or R/R MM and should help address the variation in clinical practice around the choice of treatment modalities for MM.

References

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statements:

The content was clear and easy to understand

The content addressed the learning objectives

The content was relevant to my practice

I will change my clinical practice as a result of this content

Your opinion matters

On average, how many patients with MGUS/smoldering MM do you see in a month?