All content on this site is intended for healthcare professionals only. By acknowledging this message and accessing the information on this website you are confirming that you are a Healthcare Professional. If you are a patient or carer, please visit the International Myeloma Foundation or HealthTree for Multiple Myeloma.

The mm Hub website uses a third-party service provided by Google that dynamically translates web content. Translations are machine generated, so may not be an exact or complete translation, and the mm Hub cannot guarantee the accuracy of translated content. The mm and its employees will not be liable for any direct, indirect, or consequential damages (even if foreseeable) resulting from use of the Google Translate feature. For further support with Google Translate, visit Google Translate Help.

The Multiple Myeloma Hub is an independent medical education platform, sponsored by Bristol Myers Squibb, GSK, Legend Biotech, Pfizer, and Roche. Funders are allowed no direct influence on our content. The levels of sponsorship listed are reflective of the amount of funding given. View funders.

Now you can support HCPs in making informed decisions for their patients

Your contribution helps us continuously deliver expertly curated content to HCPs worldwide. You will also have the opportunity to make a content suggestion for consideration and receive updates on the impact contributions are making to our content.

Find out more

Create an account and access these new features:

Bookmark content to read later

Select your specific areas of interest

View multiple myeloma content recommended for you

Predictive factors of mortality in patients with hematological malignancies diagnosed with COVID-19

During this COVID-19 pandemic, patients with hematological malignancies—who are immunocompromised because of the cancer itself, immunosuppressive therapies, or as a consequence of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation—represent a high-risk population.

Results from small studies report high mortality (32–61%) in this patient population but, because of the lack of bigger datasets, it is difficult to determine risk factors.1 Recently, Francesco Passamonti and colleagues published in Lancet Haematology the results of a retrospective study (NCT04352556) evaluating mortality and potential predictive factors associated with overall survival in 536 patients with hematological malignancies who required hospitalization for COVID-19.1

Study design

Patients included in this multicenter, retrospective cohort study (N = 536) were aged ≥ 18 years with a hematological malignancy and symptomatic and confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection, tested by reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) on nasopharyngeal swabs. These patients were admitted to an Italian hospital between February 25 and May 18, 2020.

Primary outcomes were mortality and evaluation of predictive parameters of mortality. Standardized mortality ratios between observed death in the study cohort and expected death were calculated as stratum-specific mortality rates of the comparison cohorts:

- COVID-19 cohort: general Italian population with COVID-19

- Non-COVID-19 cohort: 31,993 patients with hematological malignancies without COVID-19 (period March 1–June 22, 2019)

Secondary outcomes:

- Epidemiology

- Evolution of hematological malignancies and dynamics of viral load (not reported in the article)

The data cutoff for the analyses was June 22, 2020.

Patient characteristics

The most common COVID-19 symptoms at hospital admission (n = 451) were fever (n = 337), dyspnea (n = 231), cough (n = 204), and malaise (n = 175). Vascular events occurred in 33 patients, headaches in 28 patients, and diarrhea in 42 patients.

Baseline characteristics of the patients included in the study are reported in Table 1 by survival status.

Table 1. Baseline patient characteristics

|

*Defined as non-pneumonia and mild pneumonia. †Defined as dyspnea, respiratory frequency ≥ 30/min, oxygen saturation (SpO2) ≤ 93%, partial pressure of oxygen of arterial blood (PaO2)/fraction of inspired oxygen (FiO2) ≤ 300 mm Hg, and/or lung infiltrates > 50%. ‡Defined as respiratory failure, septic shock, and/or multiple organ disfunction or failure. |

|||

|

Characteristic |

All patients |

Survivors |

Non-survivors |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Median age, years (range) |

68 (58–77) |

64 (55–73) |

73 (66–80) |

|

Age group, n (%) |

|||

|

< 50 |

62 (12) |

51 (15) |

11 (6) |

|

50–59 |

86 (16) |

68 (20) |

18 (9) |

|

60–69 |

137 (26) |

100 (30) |

37 (19) |

|

70–79 |

158 (29) |

79 (23) |

79 (40) |

|

≥ 80 |

93 (17) |

40 (12) |

53 (27) |

|

Charlson Comorbidity Index, median (range) |

4 (3–6) |

4 (3–6) |

5 (4–7) |

|

Type of hematological malignancy, n (%) |

|||

|

Myeloid neoplasms |

175 (33) |

106 (31) |

69 (35) |

|

Myeloproliferative neoplasms |

83 (15) |

56 (17) |

27 (14) |

|

Myelodysplastic syndromes |

41 (8) |

21 (6) |

20 (10) |

|

Acute myeloid leukemias |

51 (10) |

29 (9) |

22 (11) |

|

Acute lymphoblastic leukemias |

16 (3) |

13 (4) |

3 (2) |

|

Hodgkin lymphoma |

17 (3) |

14 (4) |

3 (2) |

|

Non-Hodgkin lymphomas |

222 (41) |

138 (41) |

84 (42) |

|

Chronic lymphoproliferative neoplasms |

69 (13) |

47 (14) |

22 (11) |

|

Indolent lymphomas |

54 (10) |

33 (10) |

21 (11) |

|

Aggressive lymphomas |

99 (18) |

58 (17) |

41 (21) |

|

Plasma cell neoplasms |

106 (20) |

67 (20) |

39 (20) |

|

Progressive disease, n (%) |

81 (15) |

33 (10) |

48 (24) |

|

COVID-19 disease severity, n (%) |

|||

|

Mild* |

268 (50) |

220 (65) |

48 (24) |

|

Severe† |

194 (36) |

106 (31) |

88 (44) |

|

Critical‡ |

74 (14) |

12 (4) |

62 (31) |

Results

Of the 536 patients enrolled in the study, 451 were admitted for inpatient care and 85 for outpatient care to manage COVID-19. After a median follow-up of 20 days (range, 1–98), among those admitted for inpatient care

- 440 (98%) completed their hospital course (either discharged or died) with a median length of hospital stay of 16 days (range, 1–98):

- 20 days (range, 2–98) for survivors

- 11 days (range, 1–78) for non-survivors

- 82 (18%) required admission to the intensive care unit (ICU):

- 50 (11%) patients required immediate admission

- 32 (8%) of 401 patients who were initially not admitted were later transferred to the ICU

Among patients with severe or critical COVID-19, those admitted to the ICU were younger (HR, 0.97; 95% CI, 0.96–0.98) and had a lower Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI; HR, 0.80; 95% CI, 0.71–0.91).

Patients with non-mild (severe plus critical) COVID-19 were older (68.0 vs 65.5; p = 0.03), with a higher CCI (5.0 vs 4.4; p = 0.01) and a more recent diagnosis of hematological malignancy (time from diagnosis: 0 years [range, 2─6] vs 1 year [range, 0–5]; p = 0.003) than patients with mild COVID-19.

At the data cutoff date, 198 (37%) of patients had died:

- 52 (63%) among those admitted to the ICU (n = 82)

- 146 (32%) among those not admitted to the ICU (n = 454)

The mortality rate was calculated as 153.2 deaths (95% CI, 129.7–172.1) per 10,000 person-days, compared with 2.42 deaths per 10,000 person-days in patients with hematological malignancies without COVID-19 (from a retrospective analysis). A worse overall survival was observed in patients with non-mild COVID-19 compared with patients with mild COVID-19.

The mortality observed in the study cohort was then compared with that of the general Italian population with COVID-19 and with that of the non-COVID-19 cohort. The standardized mortality ratios are reported in Table 2.

Table 2. Standardized mortality ratios1

|

|

Standardized mortality ratio |

95% CI |

|---|---|---|

|

Study cohort vs general population with COVID-19 |

2.04 |

1.77–2.34 |

|

< 70 years |

3.72 |

2.86–4.64 |

|

≥ 70 years |

1.71 |

1.44–2.04 |

|

Study cohort vs non-COVID-19 cohort |

41.3 |

38.1–44.9 |

Factors associated with worse survival, from a multivariable Cox regression model, are reported in Table 3. Progressive disease status, COVID-19 severity, and the diagnosis of acute myeloid leukemia, non-Hodgkin lymphomas, and plasma cell neoplasms were predictive of a poor outcome.

Table 3. Predictive factors of mortality1

|

|

Deaths/patients |

HR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

|

Age (per year increase) |

— |

1.03 (1.01–1.05) |

|

Progressive disease |

48/81 |

2.10 (1.41–3.12) |

|

Type of hematological malignancy |

|

|

|

Myeloproliferative neoplasms |

27/83 |

1 |

|

Myelodysplastic syndromes |

20/41 |

1.58 (0.69–3.62) |

|

Acute myeloid leukemias |

22/51 |

3.49 (1.56–7.81) |

|

Acute lymphoblastic leukemias |

3/16 |

1.65 (0.46–5.94) |

|

Hodgkin lymphoma |

3/17 |

1.30 (0.36–4.66) |

|

Chronic lymphoproliferative neoplasms |

22/69 |

1.64 (0.77–3.51) |

|

Indolent lymphomas |

21/54 |

2.19 (1.07–4.48) |

|

Aggressive lymphomas |

41/99 |

2.56 (1.34–4.89) |

|

Plasma cell neoplasms |

39/106 |

2.48 (1.31–4.69) |

|

COVID-19 disease severity |

|

|

|

Mild |

48/268 |

1 |

|

Severe or critical |

150/268 |

4.08 (2.73–6.09) |

Data on laboratory findings at baseline were available for 308 patients; nonsurvivors (n = 132) compared with survivors (n = 176), respectively, had

- lower hemoglobin values: median difference −1.5 g/dL (95% CI, −2.0 to −0.2);

- lower platelet counts: −65,000 platelets per μL (95% CI, −95,250 to −17,000); and

- higher serum lactate dehydrogenase: 125 U/L (95% CI, 56─215).

Complications associated with hospitalization were observed in 251 (56%) of 451 hospitalized patients and included additional infections (n = 187), alteration of organ damage biomarkers (n = 124), and vascular events (n = 50).

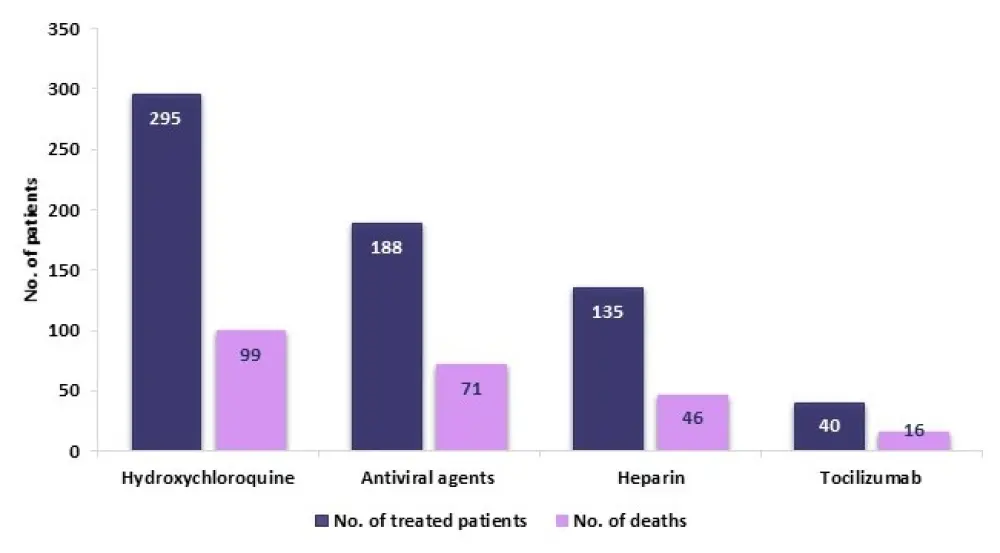

Treatments received for COVID-19, in the hospitalized patients (n = 451), are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Treatments received for COVID-19 and number of deaths occurred1

There were 233 patients on active therapy when diagnosed with COVID-19. Treatments are reported in Table 4 by survival status. Patients with chronic myeloid leukemia who received tyrosine kinase inhibitors were all alive at data cutoff. Lower mortality was observed in patients with follicular lymphoma receiving rituximab alone after remission (compared with chemotherapy).

Table 4. Treatments of hematological malignancies, at the time of COVID-19 diagnosis, among survivors and nonsurvivors1

|

HiDAC, high-dose cytarabine; IMiD, immunomodulatory drug; TKI, tyrosine kinase inhibitor. |

|||

|

Hematological malignancy |

Survivors |

Nonsurvivors |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

Myelodysplastic syndromes/acute myeloid leukemias |

All patients |

27 (62.8) |

16 (37.2) |

|

Chemotherapy |

22 (66.7) |

11 (33.3) |

|

|

HiDAC |

7 (87.5) |

1 (12.5) |

|

|

Chronic myeloid leukemia |

All patients |

13 (100.0) |

0 (0.0) |

|

TKI |

11(100.0) |

0 (0.0) |

|

|

Myelofibrosis/polycythemia |

All patients |

21 (77.7) |

6 (22.2) |

|

Ruxolitinib |

5 (55.6) |

4 (44.4) |

|

|

Non-Hodgkin lymphomas |

All patients |

58 (53.7) |

50 (46.3) |

|

Chemotherapy alone |

10 (55.6) |

8 (44.4) |

|

|

Rituximab + chemotherapy |

30 (52.6) |

27 (47.4) |

|

|

Rituximab alone |

9 (69.2) |

4 (30.8) |

|

|

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia |

Ibrutinib |

4 (44.4) |

5 (55.6) |

|

Multiple myeloma |

All patients |

24 (57.1) |

18 (42.9) |

|

IMiD-based therapy |

4 (50.0) |

4 (50.0) |

|

|

IMiDs alone |

7 (63.6) |

4 (36.4) |

|

Conclusion

This study shows that, when compared with the general population, patients with hematological malignancies diagnosed with COVID-19 had similar symptoms but a more severe disease. In addition, patients with hematological malignancies were more frequently hospitalized and had higher mortality than the general population with COVID-19 (nearly four times higher in patients < 70 years of age). Additionally, when compared with a historical non-COVID-19 cohort with hematological malignancies, the mortality of patients in the study cohort was 41 times higher.

Factors associated with significantly higher mortality were older age, progressive disease status, and disease type (acute myeloid leukemia, non-Hodgkin lymphomas, and plasma cell neoplasms). The fact that progressive disease status was one of the predictive factors of mortality suggests a benefit of treating patients to control the disease during the COVID-19 pandemic. Improved survival was seen in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia receiving tyrosine kinase inhibitors and in patients with follicular lymphoma receiving rituximab maintenance after remission. Current preliminary data do not suggest a clear protective effect of treatment with ibrutinib in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia.

Limitations of the study include its retrospective nature and the heterogeneity of hematological malignancies considered.

The prospective part of the study is ongoing.

References

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statements:

The content was clear and easy to understand

The content addressed the learning objectives

The content was relevant to my practice

I will change my clinical practice as a result of this content

Your opinion matters

On average, how many patients with MGUS/smoldering MM do you see in a month?