All content on this site is intended for healthcare professionals only. By acknowledging this message and accessing the information on this website you are confirming that you are a Healthcare Professional. If you are a patient or carer, please visit the International Myeloma Foundation or HealthTree for Multiple Myeloma.

The mm Hub website uses a third-party service provided by Google that dynamically translates web content. Translations are machine generated, so may not be an exact or complete translation, and the mm Hub cannot guarantee the accuracy of translated content. The mm and its employees will not be liable for any direct, indirect, or consequential damages (even if foreseeable) resulting from use of the Google Translate feature. For further support with Google Translate, visit Google Translate Help.

The Multiple Myeloma Hub is an independent medical education platform, sponsored by Bristol Myers Squibb, GSK, Legend Biotech, Pfizer, and Roche. Funders are allowed no direct influence on our content. The levels of sponsorship listed are reflective of the amount of funding given. View funders.

Now you can support HCPs in making informed decisions for their patients

Your contribution helps us continuously deliver expertly curated content to HCPs worldwide. You will also have the opportunity to make a content suggestion for consideration and receive updates on the impact contributions are making to our content.

Find out more

Create an account and access these new features:

Bookmark content to read later

Select your specific areas of interest

View multiple myeloma content recommended for you

Dara-(C)VRd pre- and post-ASCT for ultra-high risk MM and primary plasma cell leukemia

Patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma (NDMM) are currently treated largely using similar regimens regardless of disease status, with ~20–25% of patients experiencing an early relapse.1 These patients have a median progression-free survival (PFS) of around 24 months with modern induction and transplant pathways and seem to have a reduced response rate to second-line therapies. Using genetic risk prediction markers at diagnosis can identify patients with ultra-high risk (UHiR) NDMM and primary plasma cell leukemia (PCL), enabling the evaluation of more appropriate treatment strategies.

At the 63rd American Society of Hematology (ASH) Annual Meeting & Exposition, Martin Kaiser presented the primary endpoint analysis of the UK OPTIMUM/MUKnine trial (NCT03188172).1 Data were previously presented at the 2021 American Society of Oncology (ASCO) Annual Meeting and the European Hematology Association (EHA)2021 Virtual Congress; you can view our interview with Kaiser regarding this interim analysis below.

Why daratumumab + VRd + cyclophosphamide might be an option to consider for high-risk NDMM?

Study design and patient characteristics

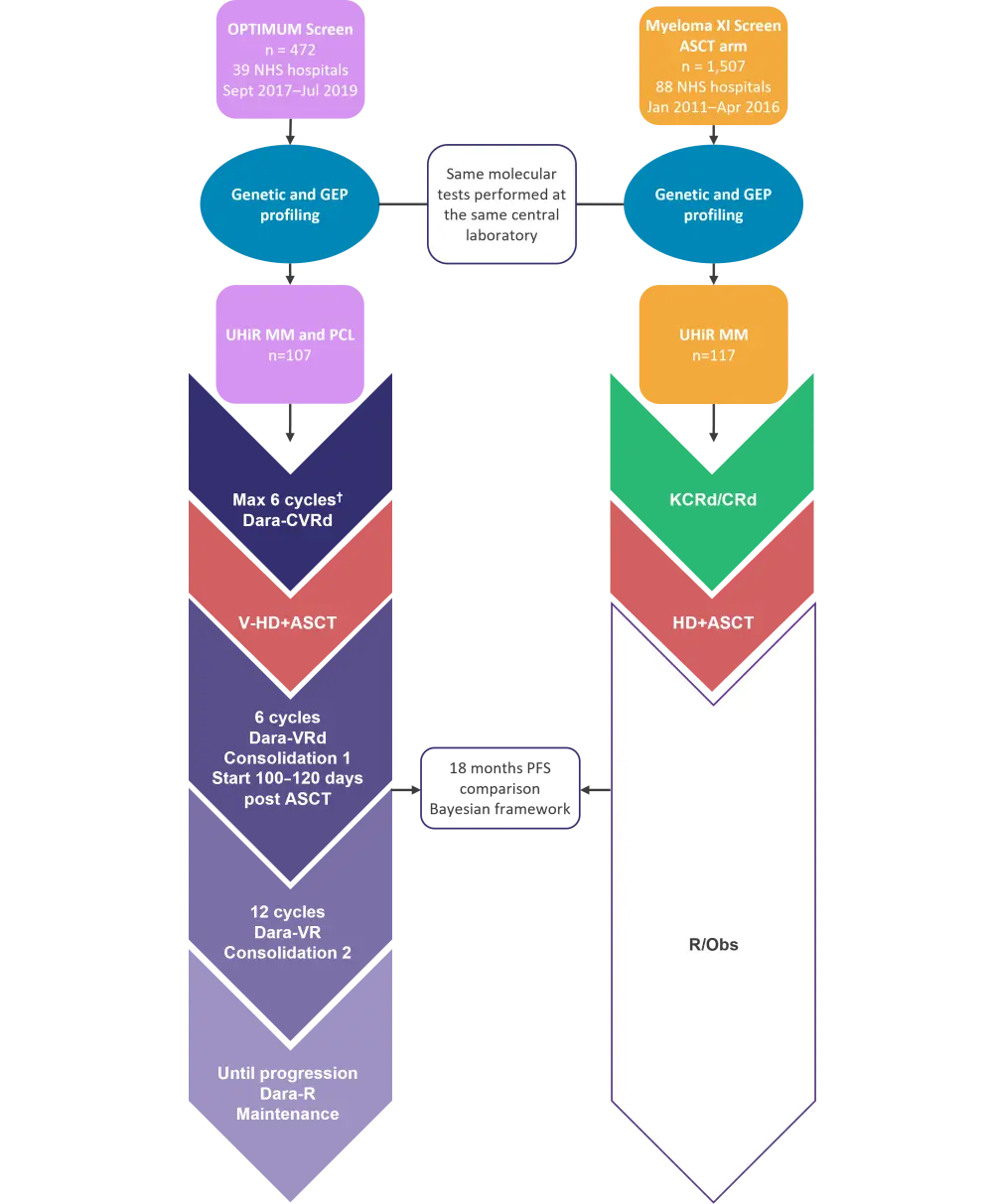

Although comparative studies are needed in the UHiR NDMM setting, randomization to standard of care versus novel treatment is challenging as patients must be informed of UHiR status, and that standard of care treatment is associated with early relapse. Therefore, the OPTIMUM study utilized a ‘digital comparator’ approach, which compared the treatment arm with an external dataset from another concurrently run trial (Myeloma XI; NCT01554852) (Figure 1). The Myeloma XI trial was a large phase III study recruiting in the same healthcare system, in the same geographical location, and utilized virtually identical entry criteria as the OPTIMUM study.2 The arm selected as the digital comparator was the ‘winning’ one of the Myeloma XI study. The study utilized pre-defined probability thresholds for a range of different outcomes and a Bayesian framework rather than more commonly used analysis methods to minimize bias. Several molecular markers can be used to predict UHiR MM, such as the presence of two or more high risk genetic markers (double hit genetics), which can convey genomic instability. These genetic markers include t4;14, t14;16, del(17p), gain(1q), and del(1p). In addition, gene expression profiling, such as the SKY92 profile which is associated with proliferation, can predict UHiR MM. The parallel profiling of both double hit genetics and gene expression profiling enabled the identification of patients with characteristics of UHiR MM for both the OPTIMUM and Myeloma XI cohorts used in this study. PCL was characterized by proliferation independently from the bone marrow microenvironment.

Figure 1. Digital comparator trial design*

ASCT, autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplant; C, cyclophosphamide; d, dexamethasone; dara, daratumumab; GEP, gene expression profiling; HD, high-dose melphalan; MM, multiple myeloma; NHS, National Health Service; PCL, plasma cell leukemia; PFS, progression-free survival; R, lenalidomide; Obs, observation; UHiR, ultra-high risk; V, bortezomib; V-HD, very high-dose melphalan.

*Adapted from Kaiser, et al.1

†Including bridging

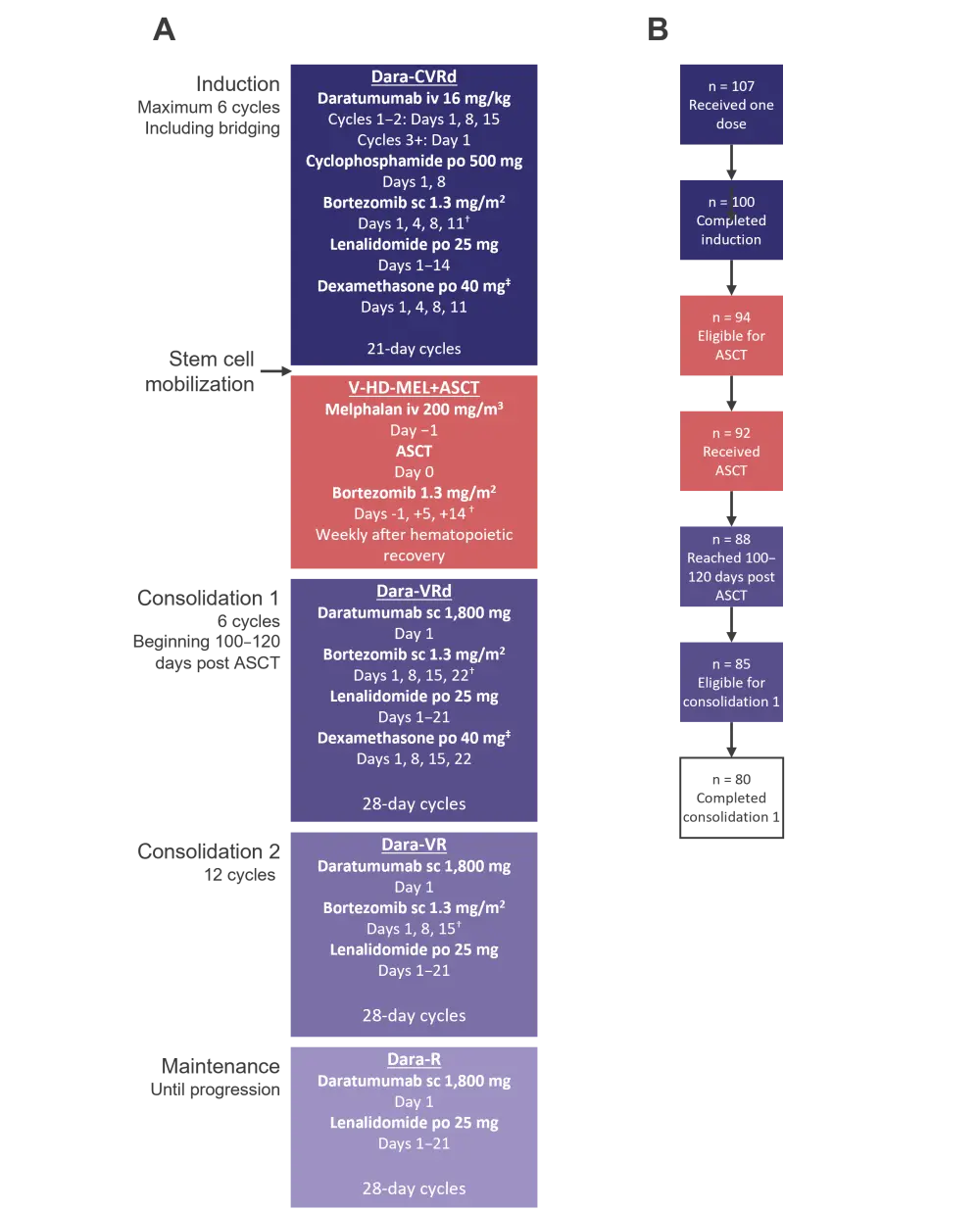

Trial therapy and the patient flow for the OPTIMUM study is detailed in Figure 2. There were 12 patients who progressed, four who died, and a total of 11 patients who withdrew, largely due to treatment side effects. There were four patients with missing follow-up data, so a total of 103 patients were included in the primary analysis population. Patient characteristics were comparable despite both cohorts being independently screened (Table 1).

Figure 2. Trial therapy and patient flow*

Schematics showing the A trial therapy and B patient flow for the OPTIMUM study.

ASCT, autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplant; C, cyclophosphamide; d, dexamethasone; dara, daratumumab; lenalidomide; iv, intravenous; po, per oral; sc, subcutaneous; UHiR, ultra-high risk; V, bortezomib; V-HD MEL, very high-dose melphalan.

*Adapted from Kaiser, et al.1

†Permissive bortezomib reduction schedule.

‡20 mg for elderly patients

Table 1. Patient characteristics*

|

ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; ISS, International Staging System. |

||

|

Characteristic, % (unless otherwise stated) |

OPTIMUM |

Myeloma XI |

|---|---|---|

|

Median age, years (range) |

60 (35–78) |

62 (33–69) |

|

Male |

59 |

57 |

|

ISS stage |

|

|

|

I |

28 |

20 |

|

II |

39 |

44 |

|

III |

32 |

32 |

|

ECOG performance status |

|

|

|

0 |

49 |

39 |

|

1 |

40 |

39 |

|

≥2 |

8 |

19 |

|

Molecular profiles |

|

|

|

Double hit genetics |

53 |

55† |

|

SKY92 risk signature present |

77 |

74† |

|

Double hit + SKY92 |

31 |

29† |

Results

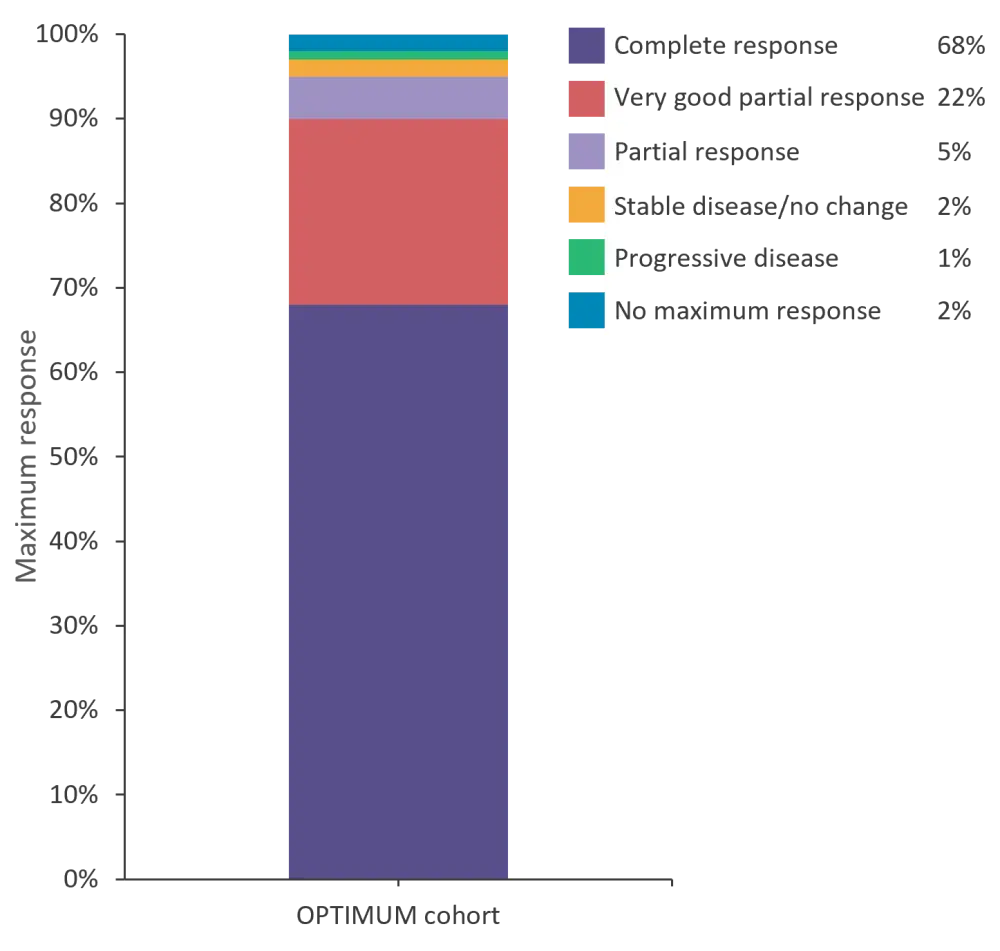

Bayesian framework modeling found that there was a 99.5% chance that treatment in the OPTIMUM cohort is superior to that of the Myeloma XI cohort (pre-specified threshold was >85% to demonstrate efficacy). After a median follow-up of 27.1 months (95% confidence interval [CI], 25.1–29.3), the median PFS was not reached for patients in the OPTIMUM cohort. PFS at 18 months was superior for the OPTIMUM cohort (81.7%; 95% CI, 74.2–89.1) vs the Myeloma XI cohort (65.9%; 95% CI, 57.3–74.4). If the Myeloma XI cohort is split into those who received KCRd (carfilzomib, cyclophosphamide, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone) vs CRd (cyclophosphamide, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone) induction, both induction methods have similar PFS at 6 months, then diverge, with KCRd-treated patients doing better. However, PFS at 18 months was still superior in the OPTIMUM cohort (81.7% vs 68.3% vs 64.5% for OPTIMUM, KCRd, and CRd, respectively). At Day 100–120 following autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (ASCT), the complete response rate was 40%, with treatment intensity seeming to deepen response over time. Maximum responses for the OPTIMUM patients are shown in Figure 3 with 68% of patients having a complete response.

Figure 3. Maximum response at the end of consolidation 1 for OPTIMUM patients (n = 107)*

*Data from Kaiser, et al.1

From a safety aspect, the most common Grade 2 adverse event (AE) during consolidation 1 was infection (24.4%) and the most common Grade 3/4 AE was thrombocytopenia (27.9%; Table 2). Grade 4 events were rare (<5%) for all categories, as previously reported in the induction phase. There was a permissive dose reduction schedule built into the OPTIMUM treatment plan, enabling 94% of patients to complete the six planned cycles of consolidation 1 therapy, despite 60.7% of patients having to reduce bortezomib treatment.

Table 2. Grade ≥2 adverse events experienced by ≥5% of patients (n = 86)*

|

*Adapted from Kaiser, et al.1 |

||

|

Adverse event, % |

Grade 2 |

Grade 3/4 |

|---|---|---|

|

Hematologic |

|

|

|

Thrombocytopenia |

15.1 |

27.9 |

|

Neutropenia |

16.3 |

21.0 |

|

Anemia |

17.4 |

3.5 |

|

Non-hematologic |

|

|

|

Infection |

24.4 |

19.8 |

|

Neuropathy |

20.9 |

3.5 |

|

Hepatic |

5.8 |

2.3 |

|

Diarrhea |

4.7 |

2.3 |

|

Dyspnea |

7.0 |

1.2 |

|

Fatigue |

17.4 |

1.2 |

|

Rash |

11.6 |

0.0 |

|

Pain |

16.3 |

0.0 |

Conclusion

Kaiser concluded the presentation by highlighting the clear 18-month PFS benefit shown when using a dara-(C)VRd (daratumumab, [cyclophosphamide], bortezomib, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone) treatment approach pre- and post-ASCT compared with KCRd + ASCT or CRd + ASCT treatment in patients with UHiR MM or PCL. A particular strength of this risk-adapted treatment regimen is its high deliverability due to the subcutaneous and oral administration of the post-ASCT therapies. In addition, the AEs were manageable during the intensified consolidation regimen. Kaiser went on to highlight that the use of a digital comparator controlled bias and limited uncertainty. This patient-centric approach utilizes existing data, improving the sustainability of trial research, and should be considered for future research.

References

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statements:

The content was clear and easy to understand

The content addressed the learning objectives

The content was relevant to my practice

I will change my clinical practice as a result of this content

Your opinion matters

On average, how many patients with MGUS/smoldering MM do you see in a month?