All content on this site is intended for healthcare professionals only. By acknowledging this message and accessing the information on this website you are confirming that you are a Healthcare Professional. If you are a patient or carer, please visit the International Myeloma Foundation or HealthTree for Multiple Myeloma.

The mm Hub website uses a third-party service provided by Google that dynamically translates web content. Translations are machine generated, so may not be an exact or complete translation, and the mm Hub cannot guarantee the accuracy of translated content. The mm and its employees will not be liable for any direct, indirect, or consequential damages (even if foreseeable) resulting from use of the Google Translate feature. For further support with Google Translate, visit Google Translate Help.

The Multiple Myeloma Hub is an independent medical education platform, sponsored by Bristol Myers Squibb, GSK, Legend Biotech, Pfizer, and Roche. Funders are allowed no direct influence on our content. The levels of sponsorship listed are reflective of the amount of funding given. View funders.

Now you can support HCPs in making informed decisions for their patients

Your contribution helps us continuously deliver expertly curated content to HCPs worldwide. You will also have the opportunity to make a content suggestion for consideration and receive updates on the impact contributions are making to our content.

Find out more

Create an account and access these new features:

Bookmark content to read later

Select your specific areas of interest

View multiple myeloma content recommended for you

Mobilizing autologous stem cells after monoclonal antibody and immunomodulatory drug-based induction therapy in MM

Despite the advent of new induction therapies, autologous stem cell transplant (ASCT) remains standard of care for young, newly diagnosed patients with multiple myeloma (MM) who are eligible for high dose chemotherapy (read more here). The benefit of incorporating monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) into pretransplant induction and posttransplant consolidation therapies has been demonstrated in trials such as CASSIOPEIA (NCT02541383) and GRIFFIN (NCT02874742). In these studies, daratumumab (dara) in combination with bortezomib (V), dexamethasone (d), and either thalidomide (T) or lenalidomide (R), respectively, has provided superior outcomes for patients with MM undergoing ASCT compared with VTd or VRd therapies alone.

Based on this success, an induction therapy combining mAbs with proteasome inhibitors (PIs) and immunomodulatory drugs (IMiDs®) is likely to become the new standard of care for patients undergoing ASCT, and it is therefore important to identify the most effective stem cell mobilization strategies for these new induction therapy combinations. During the 46th Annual Meeting of the European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (EBMT), Francesca Gay presented stem cell mobilization strategies for patients receiving mAb-based induction regimens prior to ASCT in MM.1

Mobilization strategies in MM

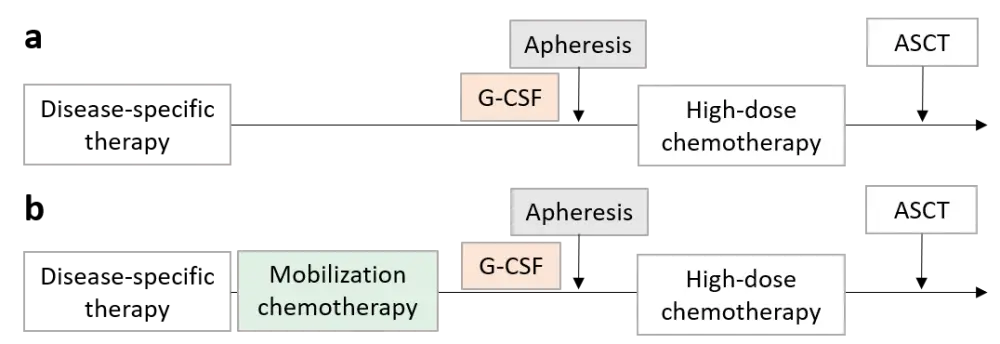

The two strategies commonly used for stem cell mobilization in patients with MM involve treatment with either granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (G-CSF) alone, or G-CSF plus chemotherapy, usually cyclophosphamide (Cy) (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Stem cell mobilization strategies commonly used for MM: (a) steady-state mobilization with cytokines alone; (b) addition of mobilization chemotherapy. Adapted from M Mohty et al.2

Previous comparisons have shown that Cy plus G-CSF provides a higher yield of stem cells than G-CSF alone,3, 4 and that intermediate-dose Cy is more effective than low-dose Cy after IMiD and PI-based induction regimens.5 More recently, plerixafor, a reversible chemokine receptor type-4 inhibitor, has been incorporated into the mobilization strategy for patients considered to be poor mobilizers, or after mobilization failure, as it promotes a more rapid harvest of stem cells in increased numbers. In patients receiving plerixafor, Cy plus G-CSF provides no greater stem cell yield to those receiving G-CSF alone,6 and accordingly, G-CSF plus plerixafor has been proposed as an alternative to G-CSF plus Cy. However, its higher cost has limited its routine use outside of clinical trials.

Factors influencing stem cell mobilization

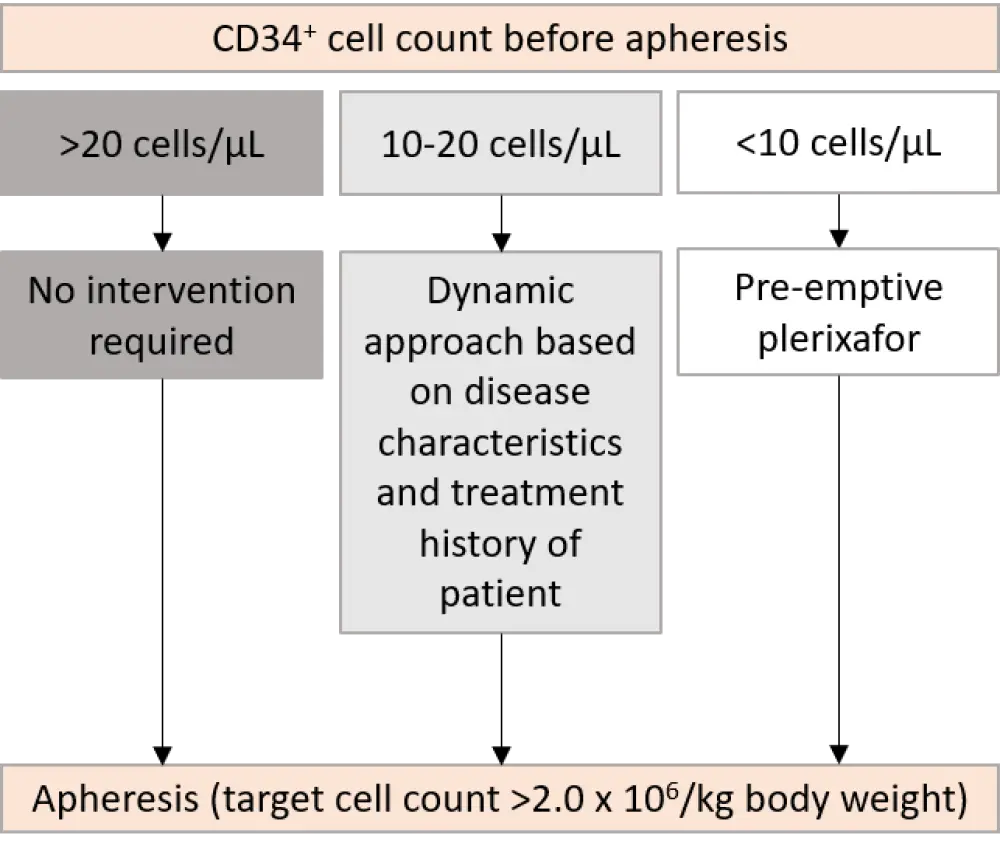

The likelihood of poor stem cell mobilization is assessed using several parameters. CD34+ cell count is routinely evaluated, and the minimum number of CD34+ cells required for ASCT is ≥ 2 × 106 CD34+ cells/kg, with an optimal number of ≥ 4 × 106 CD34+ cells/kg. However, the target collection for patients with MM tends to be higher as they often require a second ASCT at a later timepoint. Plerixafor may be administered preemptively, based upon CD34+ cell count before apheresis (Figure 2), or administered prior to the second day of apheresis if the CD34+ cell count is inadequate on the first day.7

Other parameters include:

- Treatment-related factors, for example

- types of drugs used during induction (i.e. R), use of radiotherapy, or more than one induction line as a marker of aggressive disease

- Patient-related factors, for example

- older age (> 65 years)

- Factors at mobilization, for example

- high bone marrow disease burden

- toxicity after mobilization chemotherapy

Figure 2. Preemptive plerixafor intervention according to CD34+ cell count.2

Stem cell mobilization after mAb and IMiD-based induction

Francesca Gay highlighted the importance of establishing effective mobilization strategies in patients with MM receiving mAb-based therapies as she reviewed stem cell mobilization data for the CASSIOPEIA and GRIFFIN trials (Table 1). In both trials, the proportion of patients that required plerixafor was higher for those receiving the dara-based regimen than either VTd or VRd alone (22% vs 8% and 70% vs 55%, respectively). Overall, the number of patients requiring plerixafor was higher in the GRIFFIN study, compared with CASSIOPEIA, which may be due to the differences in the percentage of patients receiving G-CSF plus Cy mobilization (all patients in CASSIOPEIA vs 6% of patients in GRIFFIN), but Francesca Gay states that we should exercise caution over the interpretation as we cannot directly compare data from two different studies. Nevertheless, the median number of CD34+ cells transplanted was adequate and equivalent across the two trials, and there were no issues with engraftment.

Table 1. Stem cell mobilization after induction with mAbs and IMiDs.1

|

Cy, cyclophosphamide; d, dexamethasone; dara, daratumumab; IMiDs, immunomodulatory drugs; mAbs, monoclonal antibodies; n.a., not available; R, lenalidomide; T, thalidomide; V, bortezomib. |

||||

|

Stem cell mobilization |

CASSIOPEIA |

GRIFFIN |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

VTd |

dara-VTd |

VRd |

dara-VRd |

|

|

Mobilization chemotherapy |

Cy 3 g/m2 100% of patients |

Cy dose n.a. ≤ 5.3% of patients |

||

|

Median number of stem cells harvested, × 106/kg |

8.9 |

6.3 |

9.4 |

8.1 |

|

Patients receiving plerixafor, % |

8 |

22 |

55 |

70 |

|

Median number of apheresis days |

1 |

2 |

n.a. |

n.a. |

|

Median number of CD34+ cells transplanted, × 106/kg |

4.3 |

3.3 |

4.8 |

4.2 |

|

Median days to neutrophil engraftment, > 500/mm3* |

13 |

13 |

12 |

12 |

|

Median days to platelet engraftment, > 20,000/mm3* |

12 |

14 |

13 |

12 |

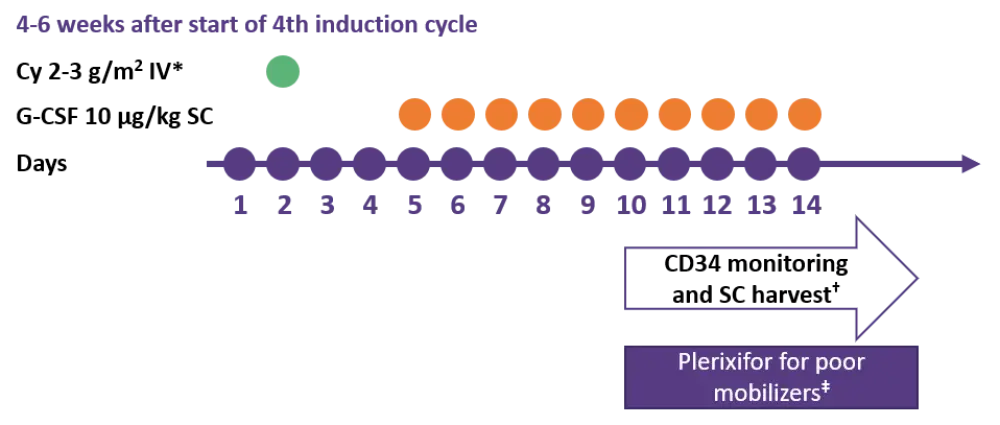

Data from studies evaluating carfilzomib (K)-based induction regimens showed that R plus d treatment had a negative impact on stem cell mobilisation, requiring more frequent use of plerixafor compared with Cy-based treatment (KRd 28% vs KCyd 6%; p < 0.001). As observed in the GMMG-CONCEPT trial, harvesting stem cells earlier and thereby reducing R and mAb pretreatment (isatuximab in this case), may help to achieve adequate stem cell yield and reduce the number of patients receiving plerixafor (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Time course of mobilization strategy for mAb and IMiD induction. Adapted from F Gay. 1

Cy, cyclophosphamide; G-CSF, granulocyte-colony stimulating factor; IV, intravenous; SC, subcutaneous.

*Dose based on patient features, toxicities during induction and disease response.

†Target ≥ 4 × 106 CD34+ cells/kg; ‡after > 4 days G-CSF in patients with CD34+ cell count < 20/µL at scheduled harvest, or who failed previous harvest attempt.

Whether to include Cy for stem cell mobilisation following mAb-based therapy should be decided based on patient features, toxicities during induction and disease response. Characteristics which favour steady-state mobilization are:

- Standard-risk disease

- Low-tumor burden

- Age ~65 years

- A good response after induction

On the other hand, chemotherapy-based mobilization would be favoured for:

- High-risk disease

- High tumor burden

- Young patients

- A poor response after induction

- Prior radiotherapy

Conclusion

Adequate numbers of autologous stem cells can be harvested following mAb-based induction therapies in ASCT-eligible patients with MM, but there is a higher likelihood that plerixafor will be required to gain sufficient stem cell yields. Multiple factors influence the choice of mobilization strategy, which can be guided by a comprehensive evaluation of patient and disease features, and drug availability.

References

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statements:

The content was clear and easy to understand

The content addressed the learning objectives

The content was relevant to my practice

I will change my clinical practice as a result of this content

Your opinion matters

On average, how many patients with MGUS/smoldering MM do you see in a month?