All content on this site is intended for healthcare professionals only. By acknowledging this message and accessing the information on this website you are confirming that you are a Healthcare Professional. If you are a patient or carer, please visit the International Myeloma Foundation or HealthTree for Multiple Myeloma.

The mm Hub website uses a third-party service provided by Google that dynamically translates web content. Translations are machine generated, so may not be an exact or complete translation, and the mm Hub cannot guarantee the accuracy of translated content. The mm and its employees will not be liable for any direct, indirect, or consequential damages (even if foreseeable) resulting from use of the Google Translate feature. For further support with Google Translate, visit Google Translate Help.

The Multiple Myeloma Hub is an independent medical education platform, sponsored by Bristol Myers Squibb, GSK, Legend Biotech, Pfizer, and Roche. Funders are allowed no direct influence on our content. The levels of sponsorship listed are reflective of the amount of funding given. View funders.

Now you can support HCPs in making informed decisions for their patients

Your contribution helps us continuously deliver expertly curated content to HCPs worldwide. You will also have the opportunity to make a content suggestion for consideration and receive updates on the impact contributions are making to our content.

Find out more

Create an account and access these new features:

Bookmark content to read later

Select your specific areas of interest

View multiple myeloma content recommended for you

Living with MM: Understanding patient and caregiver perceptions to improve HCP–patient communication

Do you know... According to a study by O’Donnell, et al., which of the following is the most common form of psychological distress experienced by caregivers of patients with multiple myeloma?

Multiple Myeloma (MM) remains an incurable condition, with progression and relapse features of a chronic disease course. MM has numerous disease and treatment comorbidities, as well as associated effects on the quality of life and performance scores of patients. Caregivers are fundamental and critical to the care of patients with MM; however, they often experience their own significant challenges.

Here, the Multiple Myeloma Hub summarizes two articles from O’Donnell, et al.1,2 The first was published in Cancer in May 2022, and describes a cross-sectional survey of patients with MM to explore their quality of life, psychological distress, and thoughts on elements of their diagnosis and prognosis.1 The second article was also published in 2022 in Blood Advances and explores the challenges and prognostic perceptions of caregivers to patients with MM.2

Study designs

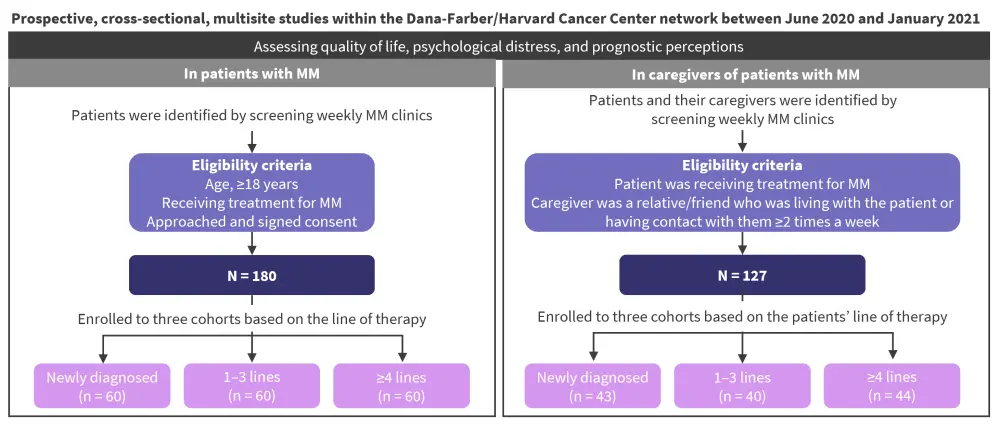

Figure 1. Study designs of the patient- and caregiver-focused surveys*

MM, multiple myeloma.

*Data from O’Donnell, et al.1 and O’Donnell, et al.2

Psychological distress and prognostic perceptions

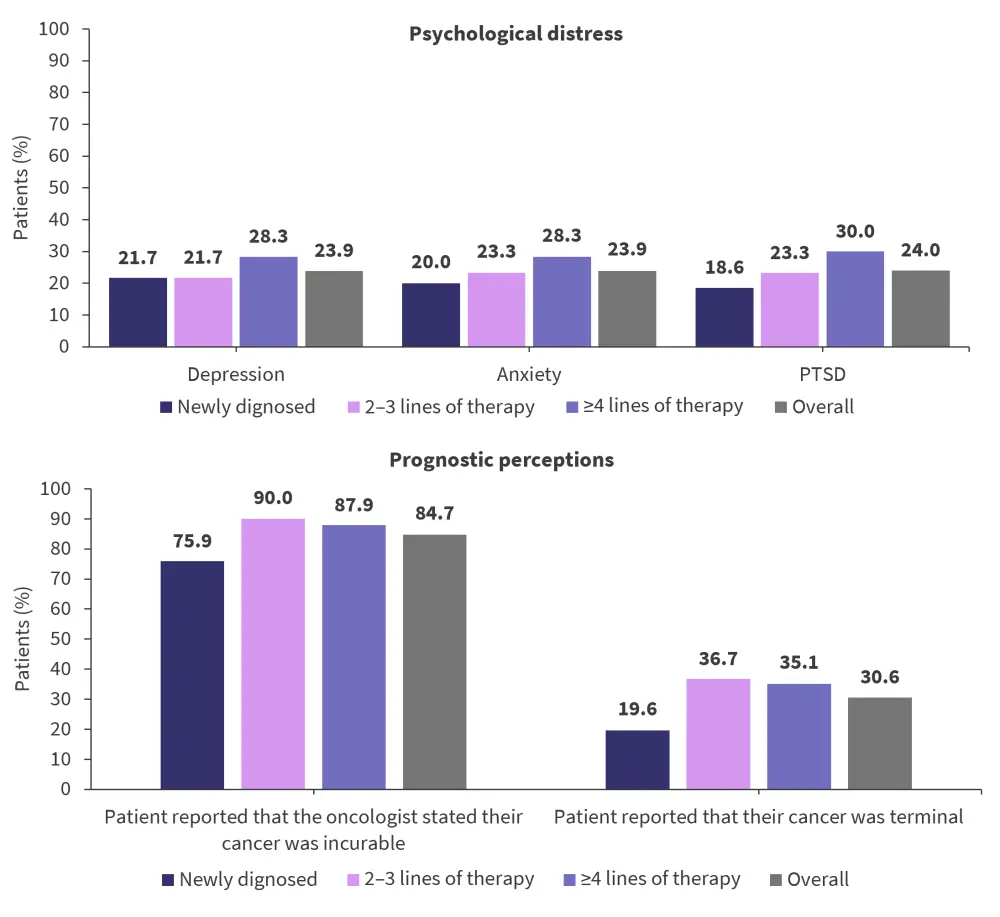

Figure 2. Patient psychological distress and prognostic perceptions according to the line of therapy*

PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder.

*Adapted from O’Donnell, et al.1

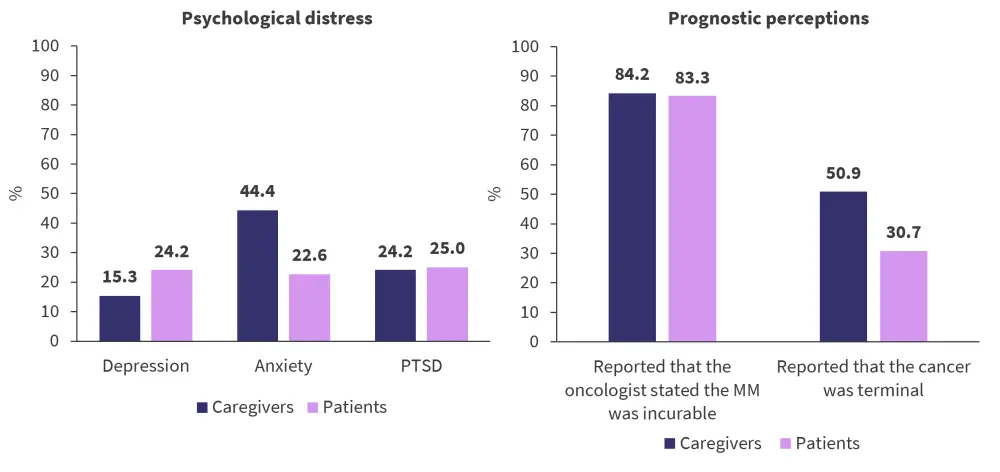

Figure 3. Psychological distress and prognostic perceptions according to caregiver–patient dyads*

MM, multiple myeloma; PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder.

*Adapted from O’Donnell, et al.2

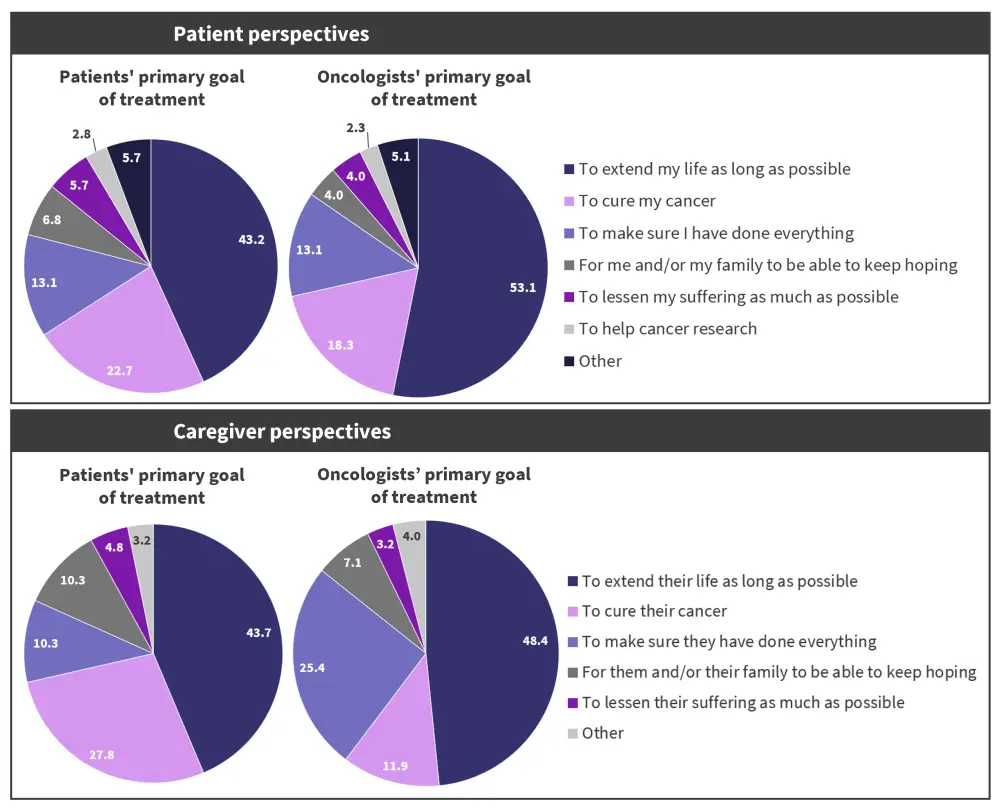

Perceptions of goals of treatment

Figure 4. Patient and caregiver perceptions of the goals of treatment compared with that of oncologists’*

*Adapted from O’Donnell, et al.1 and O’Donnell, et al.2

Key findings

- There were no statistically significant differences in the rates of psychological distress at different lines of therapy for patients with MM (Figure 2).1

- Within the caregiver study and as shown in Figure 3, while the majority of patients with MM (83.3%) reported being told their disease was incurable by their oncologist, only 30.7% acknowledged their cancer was terminal when asked at a further timepoint (at any stage of treatment). Within the same patient–caregiver dyads, a similar proportion of caregivers reported being told the disease was incurable (84.2%), but a larger proportion later stated that it was a terminal disease (50.9%) compared with patients.2

- In the caregiver study, psychological distress was also explored in the patient–caregiver dyads. Psychological issues were prevalent in both patients with MM and their caregivers; higher rates of depression were reported in patients, but higher rates of anxiety were reported in their corresponding caregivers (Figure 3).2

- As shown in Figure 4, the primary goals of care described by patients were broadly similar to what their caregivers perceived to be the primary goals.2

- However, differences existed in the caregivers’ beliefs that the primary goal of treatment of the patient compared with the treating oncologist was cure (27.8% vs 11.9%, respectively) and that the primary goal of treatment was to allow patients time to make sure they have done everything (10.3% vs 25.4%, respectively).2 Similarly, in the patient study, 22.7% of patients reported the primary goal of treatment was cure, which was greater than those who reported their treating physician’s primary goal was cure (18.3%).1

Conclusion

The results of both studies suggest that while there are common themes in the psychological challenges and prognostic understanding of patients with MM and their caregivers, some fundamental differences exist. Caregivers were more prone to anxiety than patients with MM, compared to depression being more common in patients. Caregivers were also more likely to acknowledge the disease was incurable as it progressed.

Relative to the reported treatment goals of oncologists, patients with MM were more likely to report that their treatment goal was cure and extending life was reported to be a primary goal of oncologists to a greater extent than patients, suggesting patient acknowledgement that the disease is incurable is low after their initial diagnosis. This must be considered during conversations with patients with MM and their caregivers both at diagnosis and as the disease progresses because understanding the patient’s prognosis and goals of treatment can have a significant impact on treatment decisions, quality of life, and care.

References

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statements:

The content was clear and easy to understand

The content addressed the learning objectives

The content was relevant to my practice

I will change my clinical practice as a result of this content

Your opinion matters

On average, how many patients with MGUS/smoldering MM do you see in a month?