All content on this site is intended for healthcare professionals only. By acknowledging this message and accessing the information on this website you are confirming that you are a Healthcare Professional. If you are a patient or carer, please visit the International Myeloma Foundation or HealthTree for Multiple Myeloma.

The mm Hub website uses a third-party service provided by Google that dynamically translates web content. Translations are machine generated, so may not be an exact or complete translation, and the mm Hub cannot guarantee the accuracy of translated content. The mm and its employees will not be liable for any direct, indirect, or consequential damages (even if foreseeable) resulting from use of the Google Translate feature. For further support with Google Translate, visit Google Translate Help.

The Multiple Myeloma Hub is an independent medical education platform, sponsored by Bristol Myers Squibb, GSK, Legend Biotech, Pfizer, and Roche. Funders are allowed no direct influence on our content. The levels of sponsorship listed are reflective of the amount of funding given. View funders.

Now you can support HCPs in making informed decisions for their patients

Your contribution helps us continuously deliver expertly curated content to HCPs worldwide. You will also have the opportunity to make a content suggestion for consideration and receive updates on the impact contributions are making to our content.

Find out more

Create an account and access these new features:

Bookmark content to read later

Select your specific areas of interest

View multiple myeloma content recommended for you

Extramedullary MM: Understanding predictors of development and treatment outcomes

Do you know... What is the difference in median overall survival (OS) for patients with secondary extramedullary multiple myeloma with visceral versus non-visceral disease?

Extramedullary multiple myeloma (EMM), also known as extramedullary disease (EMD), is an aggressive form of multiple myeloma. It is characterized by the ability of a clone and/or subclone to thrive and grow independent of the bone marrow microenvironment,1 and can occur at initial diagnosis (de novo) or at disease relapse (secondary).

The symptoms of EMM are typically related to the site of lesion. At diagnosis, EMM is typically found in skin and soft tissues; at relapse, typical sites involved include liver, kidneys, lymph nodes, central nervous system, breast, pleura, and pericardium.1

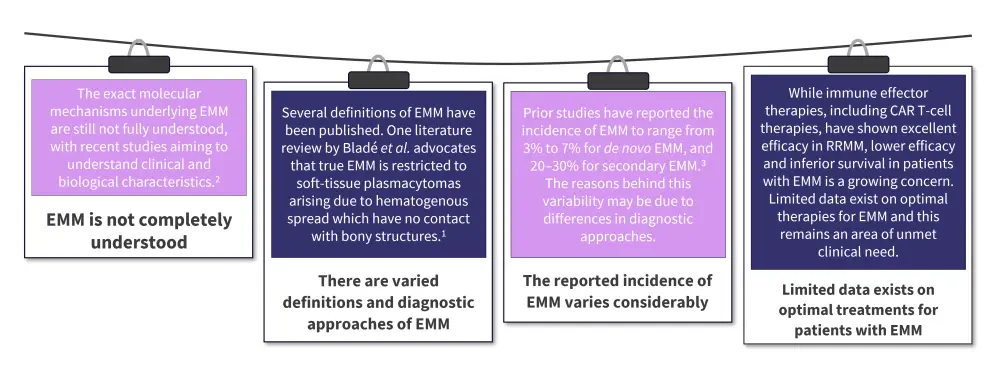

Despite treatment advances, EMM prognosis is poor and there remain several challenges in patient management (Figure 1). Further research is required to increase understanding of EMM and ultimately improve patient outcomes.

Figure 1. A snapshot of current EMM treatment challenges*

CAR, chimeric antigen receptor; EMM, extramedullary multiple myeloma; RRMM, relapsed and refractory multiple myeloma.

In this educational piece, we highlight key data from publications by Zanwar et al.3 and Gagelmann et al.,4 outlining the predictors of EMM development and treatment outcomes (including posttransplant therapy).

Identifying predictors of development

In a study by Zanwar et al.,3 204 patients with secondary EMM and 95 with de novo EMM were evaluated at a single center between 2000 and 2021. The study aimed to identify the predictors of EMM development and factors impacting prognosis and treatment outcomes. The baseline characteristics are outlined in Table 1.

To identify predictors of EMM, a 1:1 matched pair analysis was performed for comparison of baseline characteristics of patients with secondary EMM and those who had not developed EMD over a similar timeframe.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics*

|

EMM, extramedullary multiple myeloma; FLC, free light chain; IQR, interquartile range; ISS, International Staging System. |

||

|

Characteristic, % (unless otherwise stated) |

De novo EMM |

Secondary EMM |

|---|---|---|

|

Median age at multiple myeloma diagnosis, years |

61 |

58.7 |

|

Median age at EMM diagnosis |

61 |

62.4 |

|

ISS (n = 211) |

|

|

|

Stage I |

46 |

45 |

|

Stage II |

33 |

23 |

|

Stage III |

21 |

32 |

|

High-risk cytogenetics† |

53 |

54 |

|

17p depletion |

18 |

16 |

|

1q duplication |

26 |

31 |

|

t(4;14) |

15 |

16 |

|

Involved/uninvolved FLC ratio, media (IQR) |

48.8 |

106 |

|

Involved FLC value, median (IQR) |

26.8 |

39 |

Impact of sites of extramedullary disease

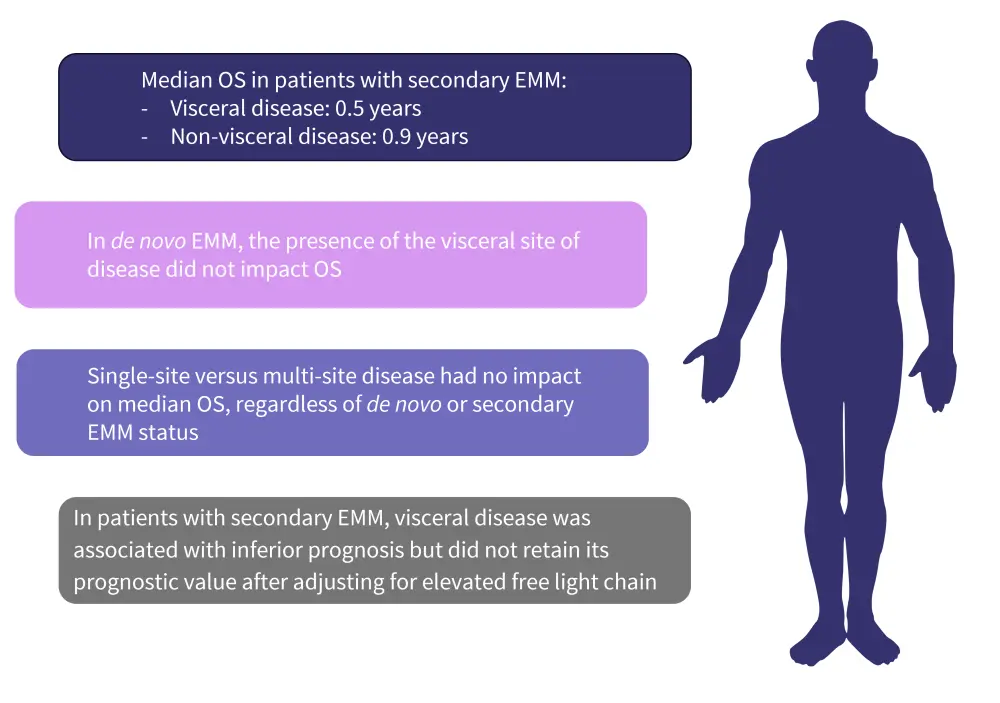

The presence of visceral versus non-visceral disease in patients with secondary EMM impacted median overall survival (OS) rates, resulting in a difference of 0.4 years. The impact of the site of extramedullary disease on OS and prognosis in patients with secondary and de novo EMM are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. The impact of the site of extramedullary disease*

EMM, extramedullary multiple myeloma; OS, overall survival.

*Data from Zanwar et al.3

Treatment outcomes for EMM3

- In both the de novo and secondary EMM cohorts, progression-free survival (PFS) with initial treatment was poor, with patients in the secondary EMM cohort experiencing the lowest PFS.

- A short duration of response was observed in those who achieved any response to treatment.

- CAR T-cell therapy yielded the highest response but did not result in durable disease control in the majority of patients.

- Failure of CAR T-cell therapies were not attributable to EMM status, with a comparable relapse rate recorded among patients with extramedullary and systemic disease.

- OS was significantly inferior in patients with EMM compared with the matched cohort.

- Factors associated with inferior OS on univariate cox proportional hazard analysis included:

- age >60 years

- International Staging System Stage 3

- high-risk cytogenetics

- presence of extramedullary disease

The impact of EMM on posttransplant outcomes4

For multiple myeloma, standard-of-care treatment for newly diagnosed fit patients includes autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT), often with posttransplant maintenance. However, there is a lack of adequate data on posttransplant maintenance therapy for patients with EMD.

The Multiple myeloma Hub has previously published an expert commentary by Gagelmann, providing key data on the impact of EMD on transplant outcomes in patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma. Below, we highlight the results of a study by Gagelmann et al. published in European Journal of Haematology. The study aimed to evaluate the characteristics and outcomes of newly diagnosed multiple myeloma patients with or without EMD after autologous transplant and different maintenance therapies.

Design4

- Outcomes were compared in 107 patients with EMD and 701 patients without EMD who received ASCT and maintenance therapy.

- In patients with EMD, the maintenance treatments included thalidomide 40%, lenalidomide 51%, and bortezomib 10%.

- The distribution of patients with paraskeletal and organ involvement were comparable across treatment groups.

Results4

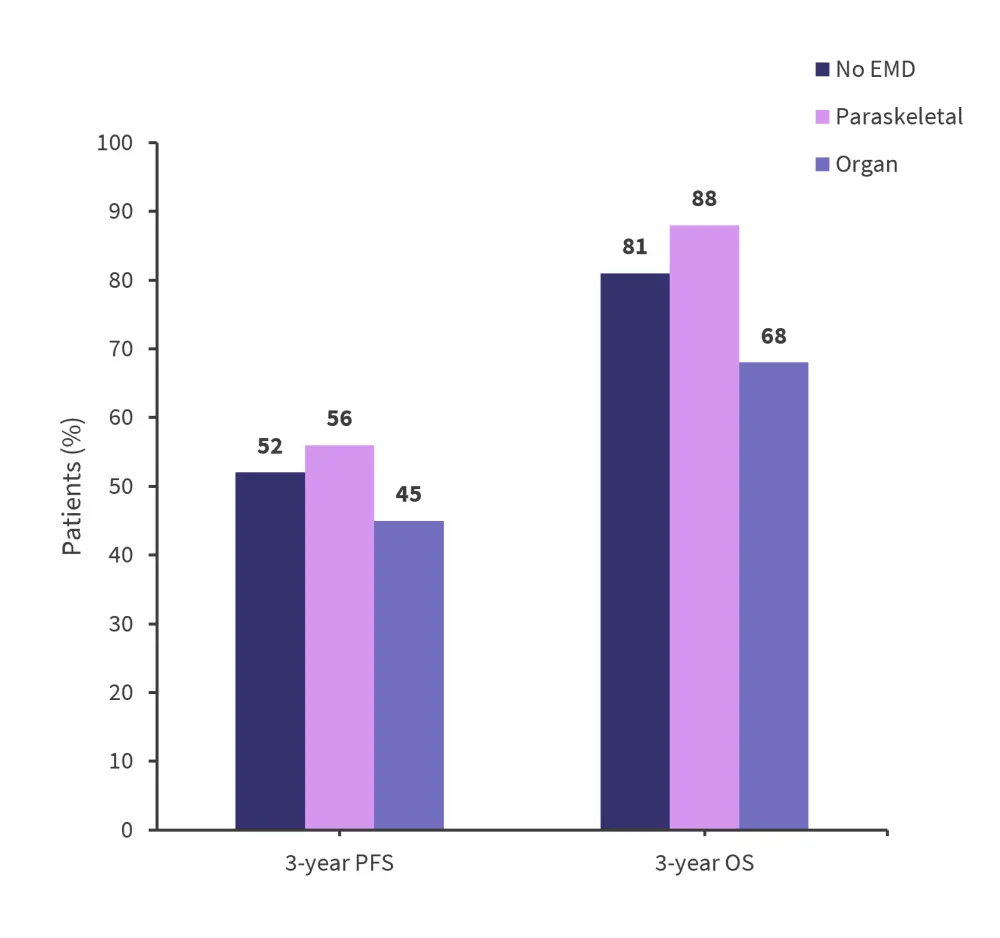

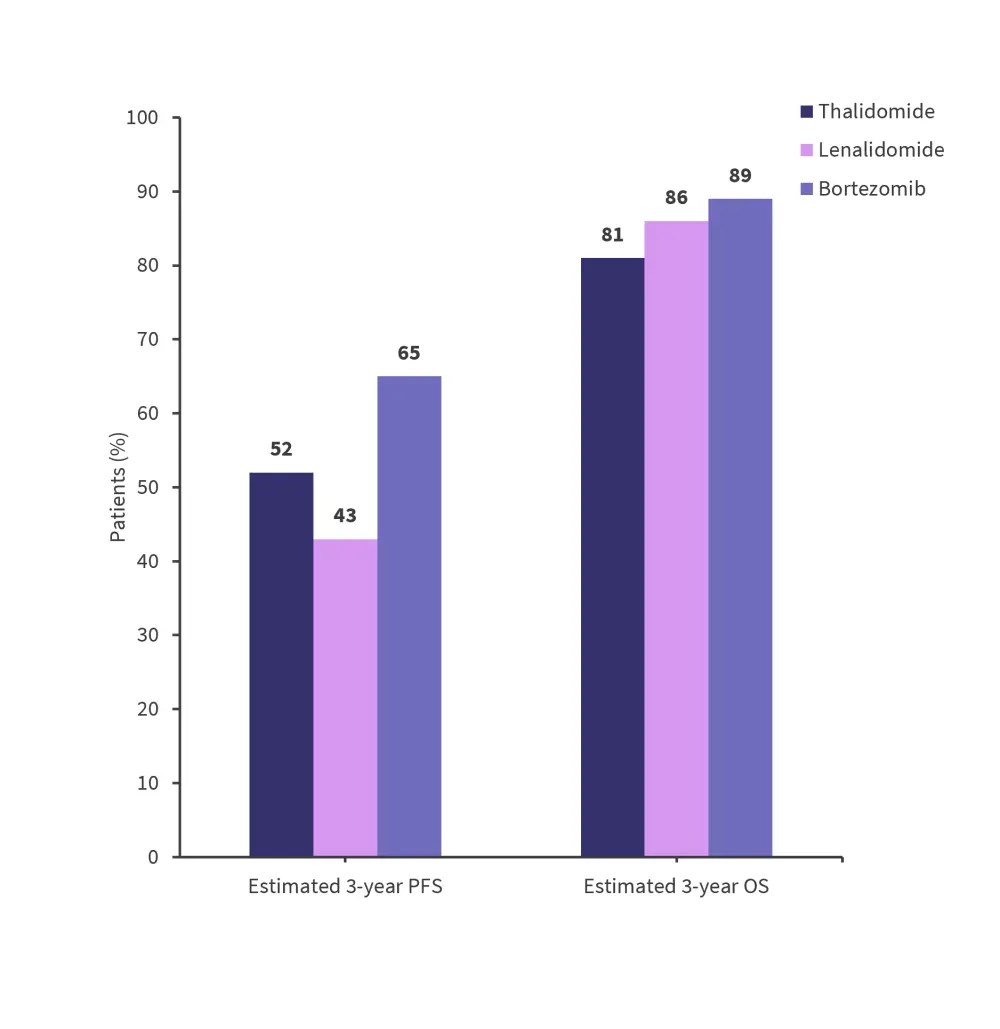

At a median follow up of 44 months, PFS and OS by the type of involvement and maintenance therapy administered (Figure 3 and 4) was recorded.

Figure 3. 3-year OS and PFS rates by type of EMM involvement*

EMD, extramedullary disease; OS, overall survival; PFS, progression-free survival.

*Data from Gagelmann, et al.4

Figure 4. Estimated 3-year PFS and OS in patients with EMD by treatment*

OS, overall survival; PFS, progression free survival.

*Data from Gagelmann, et al.4

Additional factors impacting PFS in patients with EMM:

- International Staging System

- Estimated 3-year rates were 61%, 43%, and 51% for Stage I, Stage II, and Stage III, respectively.

- Year of ASCT

- Estimated 3-year rates were 50% for ASCT between 2008 and 2011, 49% between 2012 and 2015, and 59% between 2016 and 2018.

Additional factors impacting OS in patients with EMM:

- The interval between diagnosis and first ASCT

- Estimated 3-year rates were 85% for 0–6 months, 78% for 6–12 months, and 79% for more than 12 months interval.

Conclusion

Patients with EMM typically experienced poorer posttransplant outcomes compared with those without EMM. Differences were also identified within the EMM population, with organ involvement resulting in poorer PFS and OS rates. The differences between groups were typically largest immediately after transplant and reduced after one year. There remains a lack of sufficient long-term data to bridge the knowledge gap for treating patients with EMM, and further longitudinal research is required.

References

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statements:

The content was clear and easy to understand

The content addressed the learning objectives

The content was relevant to my practice

I will change my clinical practice as a result of this content

Your opinion matters

On average, how many patients with MGUS/smoldering MM do you see in a month?