All content on this site is intended for healthcare professionals only. By acknowledging this message and accessing the information on this website you are confirming that you are a Healthcare Professional. If you are a patient or carer, please visit the International Myeloma Foundation or HealthTree for Multiple Myeloma.

The mm Hub website uses a third-party service provided by Google that dynamically translates web content. Translations are machine generated, so may not be an exact or complete translation, and the mm Hub cannot guarantee the accuracy of translated content. The mm and its employees will not be liable for any direct, indirect, or consequential damages (even if foreseeable) resulting from use of the Google Translate feature. For further support with Google Translate, visit Google Translate Help.

The Multiple Myeloma Hub is an independent medical education platform, sponsored by Bristol Myers Squibb, GSK, Legend Biotech, Pfizer, and Roche. Funders are allowed no direct influence on our content. The levels of sponsorship listed are reflective of the amount of funding given. View funders.

Now you can support HCPs in making informed decisions for their patients

Your contribution helps us continuously deliver expertly curated content to HCPs worldwide. You will also have the opportunity to make a content suggestion for consideration and receive updates on the impact contributions are making to our content.

Find out more

Create an account and access these new features:

Bookmark content to read later

Select your specific areas of interest

View multiple myeloma content recommended for you

Racial health disparities in patients with multiple myeloma: a population-based study

In the United States, differences in health associated with race or ethnicity are particularly pronounced for multiple myeloma (MM), with mortality and incidence rates in non-Hispanic (NH) Black people more than double the rates seen in the NH-White population.1 While treatment for MM has advanced in the past two decades, racial disparities have continued, particularly in respect to access to novel agents and clinical trials. A recent analysis of SEER-Medicare data revealed significantly lower utilization of the standard chemotherapeutic agent lenalidomide in African Americans as well as lower utilization of autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT), both of which are necessary in the newly diagnosed and relapsed settings for MM.2

Further clarity is needed for race- and ethnicity-related differences for cases of MM in-hospitalization. As such, Al Hadidi, et al. performed a large-scale population study, recently published in Leukemia and Lymphoma, in which they collected substantial data on multiple outcomes associated with MM hospitalization, which were stratified by race and ethnicity. We summarize key results below.1

Study design

This was a 10-year population-based study analyzing inpatient hospitalizations from 2008–2017, using information from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample.

ICD-9-CM and ICD-10-CM codes were used to identify patients with MM as well as outcomes. The study included all hospitalizations in adults (≥18 years) with an occurrence of MM in the discharge records.

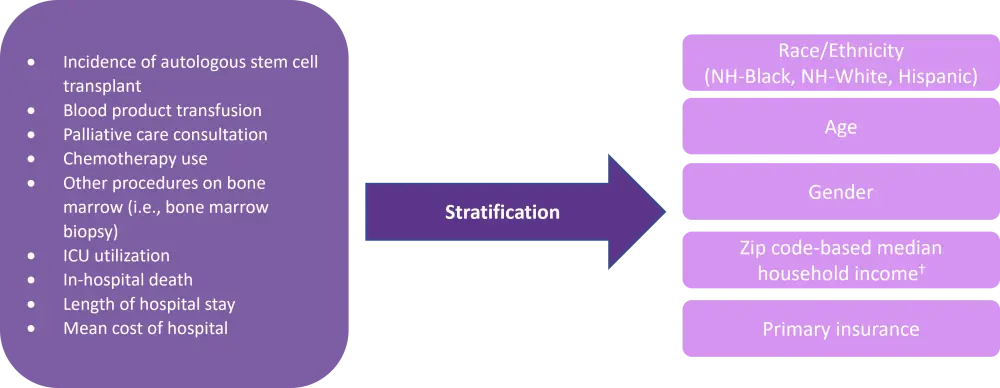

The variables associated with MM hospitalization that were investigated in this study are summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Variables associated with MM in-hospitalization and the socio-demographic characteristics used to stratify this data

ICU, intensive care unit; NH-Black, Non-Hispanic-Black; NH-White, Non-Hispanic-White.

*Adapted from Al Hadidi, et al.

†lowest quartile, 2nd quartile, 3rd quartile, highest quartile.

Results

Hospitalization rate

A total of 913,967 patients with MM were identified in the Nationwide Inpatient Sample, and the total in-hospitalization mortality rate was 5.3% (48,757).

The prevalence of MM-related hospitalizations was higher in NH-Black patients compared with NH-White patients (476.0 vs 305.6, per 100,000 hospitalizations; p < 0.001).

The prevalence of MM-related hospitalizations was also significantly higher in elderly patients, males, earners in the lower income quartile, and those who self-pay (Table 1).

Table 1. Prevalence of hospitalizations and mortality rate in patients with multiple myeloma*

|

NH-Black, non-Hispanic Black; NH-other, non-Hispanic other; NW-White, non-Hispanic White. |

|||||

|

Variables |

Myeloma |

In-hospital mortality |

p value |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

n = 913,967 |

Prevalence, per 100,000 hospitalizations |

n = 48,757 |

Incidence of in-hospital death, % |

||

|

Age |

|

|

|

|

<0.01 |

|

18–34 |

3,301 |

5.9 |

63 |

1.9 |

|

|

35–49 |

48,698 |

111.3 |

1,656 |

3.4 |

|

|

50–64 |

283,350 |

394.3 |

12,427 |

4.4 |

|

|

65+ |

578,618 |

505.4 |

34,611 |

6.0 |

|

|

Race/ethnicity |

|

|

|

|

<0.01 |

|

NH- White |

544,670 |

305.6 |

29,073 |

5.3 |

|

|

NH- Black |

186,846 |

476.0 |

9,825 |

5.3 |

|

|

Hispanic |

64,541 |

242.6 |

3,324 |

5.2 |

|

|

NH- other |

42,565 |

265.2 |

2,622 |

6.2 |

|

|

Missing |

75,347 |

292.9 |

3,914 |

5.2 |

|

|

Sex |

|

|

|

|

<0.01 |

|

Male |

496,555 |

424.7 |

27,624 |

5.6 |

|

|

Female |

417,099 |

247.0 |

21,118 |

5.1 |

|

|

Missing |

314 |

349.7 |

15 |

4.8 |

|

|

Zip income quartile |

|

|

|

|

<0.01 |

|

Lowest |

245,875 |

291.4 |

13,517 |

5.5 |

|

|

2nd |

222,359 |

301.9 |

11,267 |

5.1 |

|

|

3rd |

217,727 |

331.1 |

11,598 |

5.3 |

|

|

Highest |

210,294 |

377.9 |

11,344 |

5.4 |

|

|

Missing |

17,713 |

274.4 |

1,032 |

5.8 |

|

|

Primary payer |

|

|

|

|

<0.01 |

|

Medicare |

610,759 |

463.3 |

33,284 |

5.4 |

|

|

Medicaid |

53,735 |

115.3 |

2,523 |

4.7 |

|

|

Private |

213,964 |

260.1 |

10,081 |

4.7 |

|

|

Self-pay |

33,507 |

136.2 |

2,737 |

8.2 |

|

|

Missing |

2,002 |

348.9 |

132 |

6.6 |

|

The rate of MM-related in-hospital mortality was higher in Hispanic people compared with NH-White and NH-Black patients (6.2% vs 5.3%; p < 0.001).

Hospital treatment access

Overall, NH-Black patients with MM received fewer ASCTs compared with NH-White patients (2.8 vs 3.8%), fewer palliative care consultations (4.0% vs 4.6%), less chemotherapy (10.8% vs 11.2%), and more intensive care (5.3% vs 4.3%). In contrast, NH-Black patients received more in-patient blood product transfusions than NH-White patients (23.0 vs 21.1%).

Hispanic patients received on average more ASCT and more inpatient chemotherapy than NH-White patients (Table 2).

Table 2. In-hospitalization therapeutic modality use stratified by race*

|

ASCT, Autologous stem cell transplant; ICU, intensive care unit; NH-Black, Non-Hispanic-Black; NH-White, Non-Hispanic-White. |

||||

|

Therapeutic modality, % |

NH-White |

NH-Black |

Hispanic |

p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

ASCT |

3.8 |

2.8 |

4.0 |

<0.01 |

|

Blood product transfusion |

21.1 |

23.0 |

21.1 |

<0.01 |

|

Palliative care consultation |

4.6 |

4.0 |

3.8 |

<0.01 |

|

Chemotherapy use |

11.2 |

10.8 |

12.8 |

<0.01 |

|

Inpatient bone marrow biopsy |

6.6 |

7.7 |

8.8 |

<0.01 |

|

ICU utilization |

4.3 |

5.3 |

4.4 |

<0.01 |

Following multivariate analysis, the authors identified trends of lower utilizations of ASCT, chemotherapy, and palliative care and higher utilization of ICU, blood products, and inpatient bone marrow biopsy in NH-Black patients compared with NH-White patients. Multivariate analysis also showed that Hispanic patients has significantly reduced palliative care consultation compared with NH-White patients (Table 3).

Table 3. Multivariate analysis for in-hospitalization of multiple myeloma patients*

|

ASCT, autologous stem cell transplant; CI, confidence interval; ICU, Intensive care unit; NH-Black, Non-Hispanic-Black; NH-White, Non-Hispanic-White; OR, odds ratio. |

|||

|

Outcomes (NH-White patients as reference) |

OR |

95% CI |

p value |

|---|---|---|---|

|

In-hospital death |

|

|

|

|

NH-Black |

1.02 |

0.96–1.08 |

0.50 |

|

Hispanic |

0.99 |

0.90–1.08 |

0.74 |

|

ASCT |

|

|

|

|

NH-Black |

0.68 |

0.58–0.79 |

<0.01 |

|

Hispanic |

0.91 |

0.74–1.12 |

0.38 |

|

Blood product transfusion |

|

|

|

|

NH-Black |

1.12 |

1.06–1.18 |

<0.01 |

|

Hispanic |

1.01 |

0.92–1.10 |

0.90 |

|

Chemotherapy use |

|

|

|

|

NH-Black |

0.91 |

0.84–0.98 |

0.02 |

|

Hispanic |

1.04 |

0.92–1.18 |

0.52 |

|

Palliative care consultation |

|

|

|

|

NH-Black |

0.91 |

0.85–0.97 |

0.01 |

|

Hispanic |

0.83 |

0.75–0.93 |

<0.01 |

|

ICU utilization |

|

|

|

|

NH-Black |

1.24 |

1.17–1.32 |

<0.01 |

|

Hispanic |

1.00 |

0.91–1.11 |

0.95 |

Length and cost of hospital stay

The mean length of stay for patients hospitalized was one day longer for Hispanic and NH-Black patients compared with NH-White patients, while the mean cost of hospitalization (USD) was higher for NH-Black patients versus NH-White patients (Table 4).

Table 4. The mean cost of hospitalization and mean length of stay stratified by race*

|

NH-Black, Non-Hispanic-Black; NH-White, Non-Hispanic-White; SD, standard deviation; USD, U.S dollars. |

||||

|

|

NH-White |

NH-Black |

Hispanic |

p value† |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Mean cost of hospitalization (SD), USD |

16,516.8 (322.8) |

16,971.91 (285.9) |

19,190.5 (395.6) |

0.62 |

|

Mean length of stay (SD), days |

6.9 (1.2) |

7.83074 (1.3) |

7.7 (1.6) |

0.38 |

Average annual percent change

Overall, there was a statistically significant decline of in-hospital mortality among all MM patients when measured by an average annual percentage change (AAPC) (AAPC: -3.0; 95% confidence interval [CI], −4.2 to −1.8; p < 0.001). However, when stratifying by race, NH-White patients had the most significant in-hospital mortality improvement with an AAPC of -3.8 (95% CI, −5.4 to −2.3; p < 0.001). For NH-Black patients, the decline of in-hospital mortality was not statistically significant (AAPC: -2.2, 95% CI, −4.7 – 0.4).

Conclusion

This large-scale population study provided further evidence for a racial/ethnic imbalance regarding access to healthcare and disease burden in patients with MM. NH-Black patients had a higher prevalence of hospitalisations and greater in-hospitalization mortality compared with NH-White patients, while being provided fewer vital therapeutic modalities including ASCT and chemotherapy. Both NH-black and Hispanic patients also received fewer palliative care consultations to help manage symptoms. These differences call for urgent action to improve the current healthcare system in order to provide equity for the population suffering from MM in the US.

References

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statements:

The content was clear and easy to understand

The content addressed the learning objectives

The content was relevant to my practice

I will change my clinical practice as a result of this content

Your opinion matters

On average, how many patients with MGUS/smoldering MM do you see in a month?