All content on this site is intended for healthcare professionals only. By acknowledging this message and accessing the information on this website you are confirming that you are a Healthcare Professional. If you are a patient or carer, please visit the International Myeloma Foundation or HealthTree for Multiple Myeloma.

The mm Hub website uses a third-party service provided by Google that dynamically translates web content. Translations are machine generated, so may not be an exact or complete translation, and the mm Hub cannot guarantee the accuracy of translated content. The mm and its employees will not be liable for any direct, indirect, or consequential damages (even if foreseeable) resulting from use of the Google Translate feature. For further support with Google Translate, visit Google Translate Help.

The Multiple Myeloma Hub is an independent medical education platform, sponsored by Bristol Myers Squibb, GSK, Legend Biotech, Pfizer, and Roche. Funders are allowed no direct influence on our content. The levels of sponsorship listed are reflective of the amount of funding given. View funders.

Now you can support HCPs in making informed decisions for their patients

Your contribution helps us continuously deliver expertly curated content to HCPs worldwide. You will also have the opportunity to make a content suggestion for consideration and receive updates on the impact contributions are making to our content.

Find out more

Create an account and access these new features:

Bookmark content to read later

Select your specific areas of interest

View multiple myeloma content recommended for you

Racial differences in clinical trial enrollment, treatment, and survival outcomes in MM

Although there are racial variations in the presentation, treatment, and outcomes of many cancers, racial disparities are particularly pronounced in multiple myeloma (MM). Black people are twice as likely as white people to develop monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance, the precursor of MM.1 It is also well known that this translates into a two- to three-fold higher incidence of MM, yet studies of mortality and outcomes have been inconclusive.2 It has also been suggested that the representation and reporting of racial minorities in MM trials has been low, which will affect the understanding of the racial disparities seen in the course of MM.3

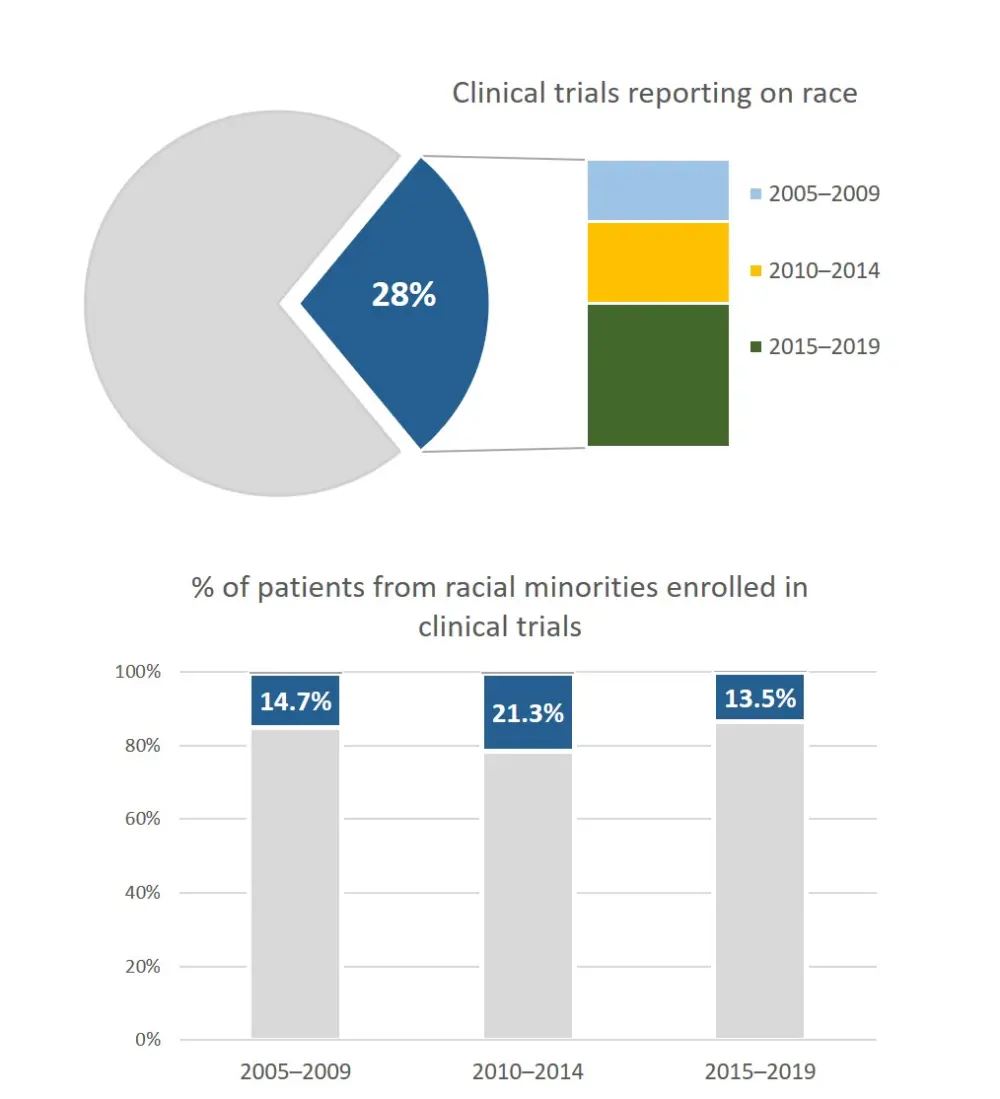

In a recent systematic review published in Lancet Haematology, Ghulam Rehman Mohyuddin and team commented on the reporting and enrolment of racial minorities in MM randomized controlled trials (RCTs) between 2005 and 2019.3 They identified 100 RCTs that met their inclusion criteria, which included 45,524 patients. The group found that only 26 RCTs reported the racial composition of their enrolled cohorts, and among the 16,452 patients in these trials, 2,612 (16%) were non-white. Only 19 studies reported the number of black patients: 730 (6%) of 12,915 patients. The study assessed the reporting over different periods and found that it had remained stable and that the enrolment of minorities had not changed for the last 15 years (Figure 1). They also found that reporting of race in studies was slightly better in pharmaceutical-led vs academic-led trials (33% vs 18%; p = 0.09). Multinational studies were more likely to recruit minorities than single-country studies (18% vs 13% of patients; p < 0.0001), but the same proportion reported on their study population's racial composition. They conclude that the research community should take steps to rectify the under-representation and reporting of minorities in trials to provide appropriate counseling and equitable care.3

Figure 1. Multiple myeloma clinical trials reporting on race and representation of racial minorities3

A recent publication by Benjamin Derman and colleagues aimed to assess outcomes in a cohort of patients with MM and identify any differences between black and white patients. Their study was published recently in the Blood Cancer Journal.2

Using the Multiple Myeloma Research Foundation (MMRF) CoMMpass registry (NCT01454297), the team included a total of 639 evaluable patients (Table 1). The CoMMpass study collected tissue samples, genetic information, quality of life, and outcomes from patients mainly from the US diagnosed with MM. Cytogenetic changes were inferred from next-generation sequencing CoMMpass data.2

Table 1. Patient characteristics from the MMRF CoMMpass registry2

|

Characteristic |

White (n = 526) |

Black (n = 113) |

p value |

|

ASCT, autologous stem cell transplant; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; IMiD, immunomodulatory drug; PI, proteasome inhibitor. |

|||

|

Age, median (range) |

65 (38–89) |

63 (34–87) |

0.2 |

|

Male gender |

319 (61) |

69 (61) |

0.9 |

|

Number of high-risk cytogenetic abnormalities |

|

|

|

|

0 |

254 (48) |

58 (51) |

0.6 |

|

1 |

200 (38) |

43 (38) |

0.5 |

|

2+ |

72 (14) |

12 (11) |

0.4 |

|

ECOG performance status |

|

|

0.8 |

|

0 |

164 (35) |

34 (34) |

|

|

1 |

231 (49) |

45 (45) |

|

|

2 |

56 (12) |

15 (15) |

|

|

3 |

21 (4) |

6 (6) |

|

|

4 |

4 (1) |

1 (1) |

|

|

Induction therapy |

|

|

0.001 |

|

Any triplet |

384 (73) |

62 (55) |

<0.001 |

|

PI + IMiD triplet |

240 (46) |

40 (35) |

0.05 |

|

Alkylator-based triplet |

144 (27) |

22 (20) |

0.1 |

|

Doublet |

118 (22) |

46 (41) |

<0.001 |

|

Other |

24 (5) |

5 (4) |

1 |

|

Received triplet + ASCT |

231 (44) |

37 (33) |

0.04 |

|

Received frontline ASCT |

260 (49) |

44 (39) |

0.04 |

|

+ Post-ASCT maintenance |

157 (60) |

26 (59) |

0.9 |

Median age, male gender, high-risk cytogenetic abnormalities, and Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group status were similar across the groups. Black patients were significantly less likely to receive triplet therapies than white patients (55% vs 73%; p < 0.001). Black patients were also less likely to receive frontline autologous stem cell transplant (ASCT; 39% vs 49%; p = 0.04) and combination triplet induction with ASCT (33% vs 44%; p = 0.04).2

In terms of survival outcomes, overall survival (OS) was shorter in black patients compared with white patients (age-adjusted HR, 1.7; 95% CI, 1.2–2.4; p = 0.003), though this was attenuated in patients who received triplet therapy and ASCT. On multivariate analysis, only the lack of frontline ASCT was associated with worse progression-free survival and OS in black patients. Subgroup analysis of those patients who received triplet therapy plus ASCT suggests that the effect on OS is only partially corrected by this combination treatment (age-adjusted HR, 2.3; 95% CI, 0.9–5.8; p = 0.08).2

The team concluded that the reduced OS seen in black patients was not completely overcome by controlling for socioeconomic status surrogate measures, such as access to standard treatment regimens, and that there may be biological or other socioeconomic factors at work in the racial disparities seen in MM outcome.2

A study from England that was published in 2015 in Leukemia and Lymphoma agreed that the incidence of MM was higher in black patients (age-standardized incidence rate, 15.00 per 100,000; 95% CI, 13.50–16.40) than white (6.11 per 100,000; 95% CI. 6.00–6.22), but found that relative survival was better in black patients at 1 (HR, 0.66; 95% CI, 0.55–0.79) and 3 years (HR, 0.69; 95% CI, 0.58–0.83) than white patients. They found similar outcomes in the South Asian group at 1 (HR, 0.65; 95% CI, 0.51–0.82), 3 (HR, 0.72; 95% CI, 0.57–0.90), and 5 years (HR, 0.68; 95% CI, 0.50–0.92). The UK study found a marked increase in ASCT being given to black and Asian patients in 1994–2000 and 2001–2009. The group postulate that, while access to treatments may have been inequitable previously, the more equitable access to treatments seen latterly in England may account for the better outcomes in minority groups. They felt that this could enable the study of biological differences in outcomes, especially with novel therapies.4

References

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statements:

The content was clear and easy to understand

The content addressed the learning objectives

The content was relevant to my practice

I will change my clinical practice as a result of this content

Your opinion matters

On average, how many patients with MGUS/smoldering MM do you see in a month?