All content on this site is intended for healthcare professionals only. By acknowledging this message and accessing the information on this website you are confirming that you are a Healthcare Professional. If you are a patient or carer, please visit the International Myeloma Foundation or HealthTree for Multiple Myeloma.

The mm Hub website uses a third-party service provided by Google that dynamically translates web content. Translations are machine generated, so may not be an exact or complete translation, and the mm Hub cannot guarantee the accuracy of translated content. The mm and its employees will not be liable for any direct, indirect, or consequential damages (even if foreseeable) resulting from use of the Google Translate feature. For further support with Google Translate, visit Google Translate Help.

The Multiple Myeloma Hub is an independent medical education platform, sponsored by Bristol Myers Squibb, GSK, Legend Biotech, Pfizer, and Roche. Funders are allowed no direct influence on our content. The levels of sponsorship listed are reflective of the amount of funding given. View funders.

Now you can support HCPs in making informed decisions for their patients

Your contribution helps us continuously deliver expertly curated content to HCPs worldwide. You will also have the opportunity to make a content suggestion for consideration and receive updates on the impact contributions are making to our content.

Find out more

Create an account and access these new features:

Bookmark content to read later

Select your specific areas of interest

View multiple myeloma content recommended for you

Do you know... Which health goal was most frequently selected in a survey of older frail patients with MM?

Measures of success in the management of multiple myeloma (MM) typically center around survival and tolerability of adverse events (AEs), particularly in the development of novel therapies in clinical trials. There is more scope for individualized treatment strategies in real-world practice, but these still tend to be primarily informed by disease characteristics such as staging and cytogenetics.

The average age of MM diagnosis is 65 years, meaning that a high proportion of patients are elderly. Determinants of frailty include age, patient independence, and the degree of ability to carry out daily activities. Advanced age at diagnosis, paired with disease burden, increases the incidence of frailty.

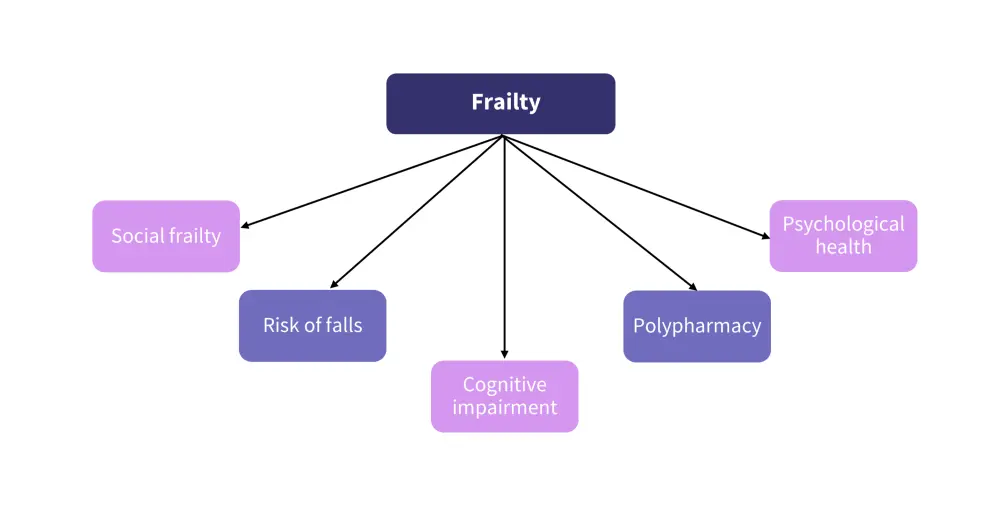

Frailty in MM1

There are several additional considerations for the management of patients with increased frailty due to its association with a range of secondary risks (Figure 1).

An increased risk of falls and difficulty taking on activities of daily living independently are commonly associated with frailty. This introduces a host of other considerations for treatment, including the feasibility of patient transport to care centers and subsequent disruption to the patient’s social life and quality of life (QoL).

Figure 1. Factors secondary to frailty in patients with MM*

MM, multiple myeloma.

*Adapted from O’Donnell.1

Frailty has also been found to be a significant predictor of survival in MM, more so than disease stage or cytogenetic risk alone. This highlights the need for individualized treatment plans that consider QoL, access to care, and disease status.

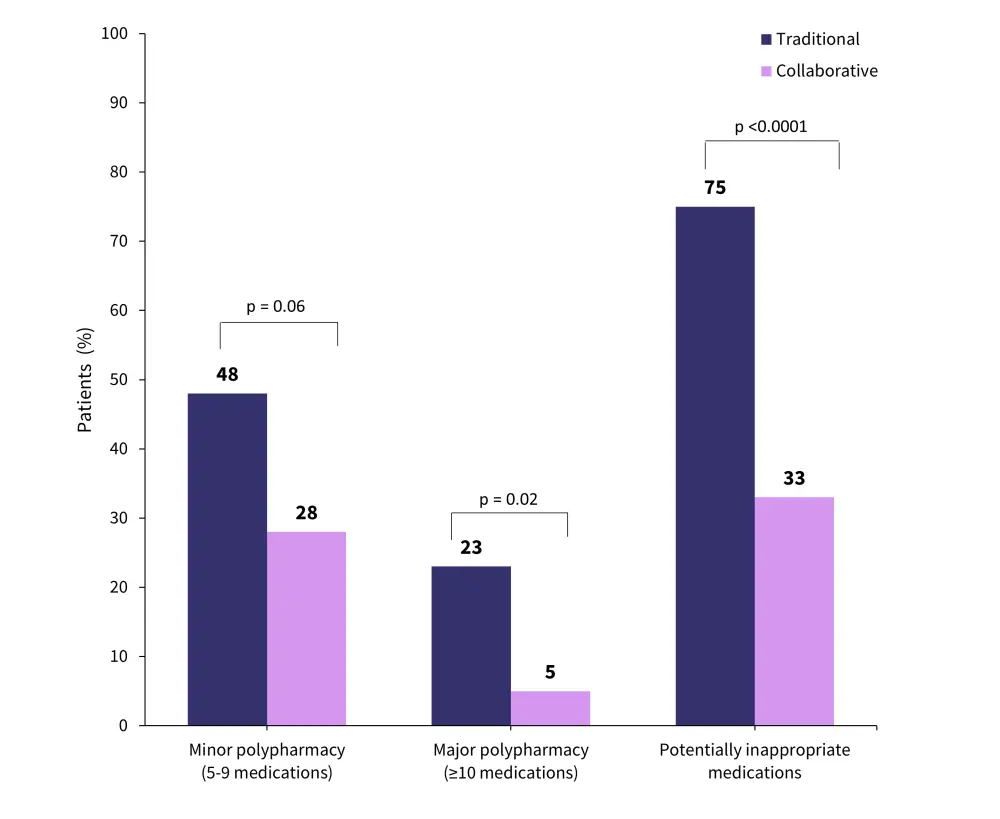

Polypharmacy1

Patients with MM were prescribed a median of ten medications at any one time. Polypharmacy was associated with an increased risk of adverse drug reactions, drug-drug interactions, falls, and poorer adherence to lenalidomide.1

However, polypharmacy in MM may be mitigated by collaboration between physicians and pharmacists. Figure 2 shows the influence of collaboration, notably in the percentage of patients prescribed potentially inappropriate medications reducing from 75% to 33%.

Figure 2. Impact of traditional and collaborative MM treatment on polypharmacy*

MM, multiple myeloma.

*Data from Sweiss, et al.2

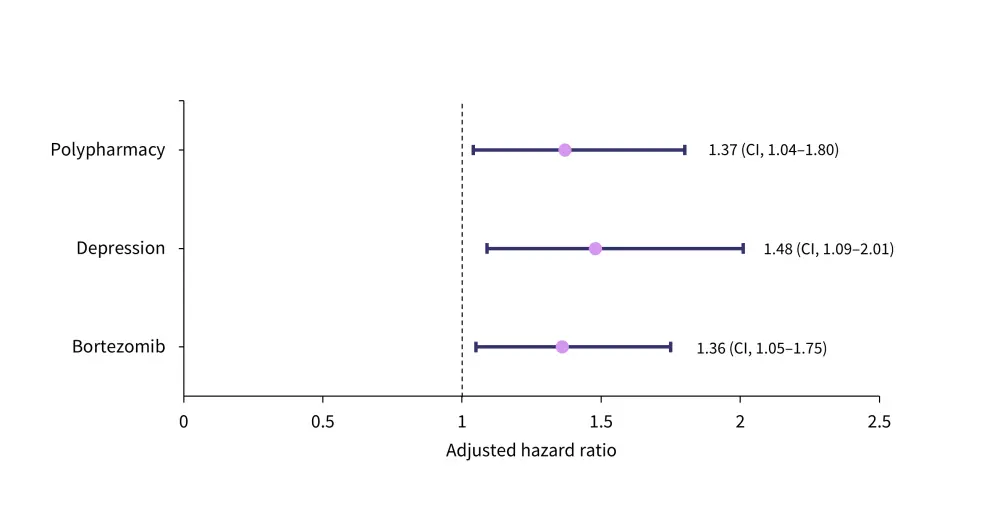

Falls

Patients with MM are a particularly high-risk group for injuries as age, frailty, and some common MM therapies are all associated with an increased risk of falls. A study showed that the risk of falls in the control population was 23% compared with 26% in patients diagnosed with MM at ≤1 year and 33% at ≥1 year.3

Figure 3. Factors associated with increased risk of falls in frail patients with MM*

aHR, adjusted hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; MM, multiple myeloma.

*Data from Schoenbeck, et al.4

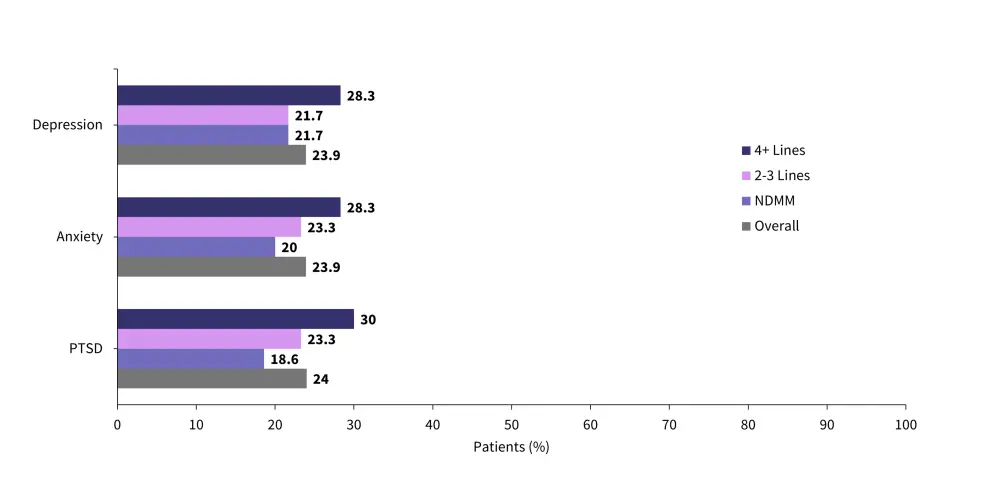

Psychological health1

Patients with MM have an increased risk of declining psychological health due to a higher incidence of loneliness and reduced independence, especially in frail patients. Patients with MM have a higher risk of developing mental health conditions, with 12.6% reporting suicidal ideations. Mental health conditions were observed to increase as patients progressed along the lines of therapy (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Incidence of mental health conditions in patients with MM*

MM, multiple myeloma; NDMM, newly diagnosed multiple myeloma; PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder.

*Data from O’Donnell.1

Social frailty1

Frail individuals with MM are more likely to have difficulty completing activities of daily living, making it difficult to meet their basic social needs and therefore increasing the risk of social frailty. Social frailty is a significant predictor of progression-free survival and overall survival rates, more so than older age or frailty alone (Table 1).

Table 1. Predictive factors of PFS and OS in MM*

|

CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; IMWG, International Myeloma Working Group; ISS, International Staging System. |

||||

|

Variable |

Progression-free survival |

Overall survival |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

HR (95% CI) |

p value† |

HR (95% CI) |

p value† |

|

|

Age ≥75 years |

1.15 (0.76–1.75) |

0.507 |

1.21 (0.73–2.00) |

0.462 |

|

High-risk cytogenetics |

1.62 (1.10–2.39) |

0.015 |

1.18 (0.70–2.01) |

0.534 |

|

ISS, stage III |

1.32 (0.93–1.87) |

0.123 |

1.69 (1.06–2.68) |

0.026 |

|

IMWG frailty score ≥2 |

1.62 (1.11–2.37) |

0.013 |

2.57 (1.45–4.55) |

0.001 |

|

Triplet regimen |

0.95 (0.66–1.35) |

0.759 |

0.92 (0.58–1.45) |

0.713 |

|

Social frailty score ≥2 |

1.74 (1.17–2.59) |

0.007 |

2.84 (1.73–4.67) |

<0.001 |

Patient-preferences1

Frailty and its effects influence patient preferences and individual MM treatment goals. For instance, younger, fit patients may be more likely to tolerate pain and AEs to increase their probability of longer overall survival. However, frail patients already have a decreased QoL compared with younger, fitter patients. In a survey of 121 older adults starting chemotherapy, QoL, cognition, and independence were consistently preferred over length of life (Table 2).

Table 2. Patient-defined treatment goals amongst older adults for MM*

|

QoL, quality of life. |

|||||

|

Goal (%, unless otherwise specified) |

Strongly agree |

Agree |

Neither agree or disagree |

Disagree |

Strongly disagree |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Length of life is the most important goal, no matter the QoL |

13 |

12 |

17 |

34 |

22 |

|

The ability to take care of myself is more important than a longer life |

28 |

31 |

16 |

13 |

7 |

|

Maintaining thinking ability is more important than a longer life |

41 |

40 |

14 |

2 |

1 |

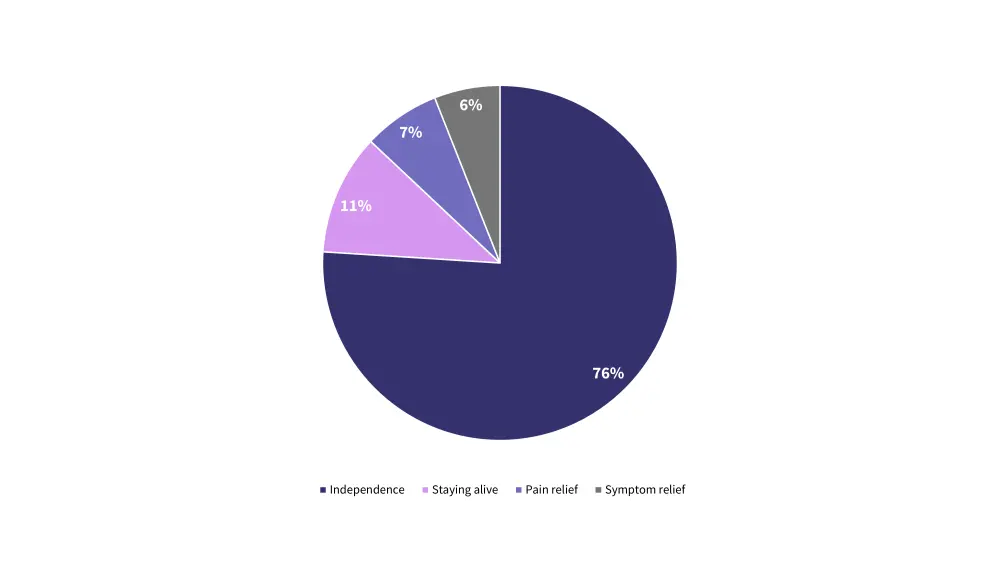

In another survey in which patients were asked their most important health goal, independence was most commonly selected as a primary goal. The other common health goals are shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5. Most important health goals for patients with multiple myeloma*

*Data from Fried, et al.7

To facilitate patients in achieving their goals, a host of considerations can be made, notably managing comorbidities, upfront dose modifications, and focusing on pain reduction. Applying a multidisciplinary approach to treatment (such as collaboration with pharmacists to reduce polypharmacy) can help reduce some of the risks contributing to poor outcomes, which in turn can help minimize falls and promote independence.

Conclusion

All patients, regardless of age or disease status, have personal goals for treatment that are vital to consider when developing a treatment plan. However, frail patients with MM are more likely to be susceptible to AEs, a lack of independence, and decreased cognition. These additional factors mean that many patients’ goals for treatment do not align with the typical goals of survival and disease management. A significant portion of frail patients valued their independence and cognition over extending their life expectancy, highlighting the importance of patient-defined goals to improve individual QoL and living with MM more manageable for these individuals.

Expert Opinion

“Multiple myeloma (MM) is primarily a disease of older adults, many of whom are frail. Frailty, which is characterized by diminished strength and reduced physiologic reserve, can create unique challenges in the management of MM. The interaction between frailty and MM can potentially impact treatment decisions, increase susceptibility to infections, and amplify the impact of side effects. Healthcare providers must adopt a personalized, multidisciplinary approach that considers the individual’s frailty status, tailor treatment plans accordingly, and provide comprehensive support for pain management and psychosocial wellbeing. By taking a personalized approach, we can enhance the quality of life for frail adults with MM and improve overall outcomes.”

Elizabeth O'Donnell

Elizabeth O'DonnellReferences

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statements:

The content was clear and easy to understand

The content addressed the learning objectives

The content was relevant to my practice

I will change my clinical practice as a result of this content

Your opinion matters

On average, how many patients with MGUS/smoldering MM do you see in a month?