All content on this site is intended for healthcare professionals only. By acknowledging this message and accessing the information on this website you are confirming that you are a Healthcare Professional. If you are a patient or carer, please visit the International Myeloma Foundation or HealthTree for Multiple Myeloma.

The mm Hub website uses a third-party service provided by Google that dynamically translates web content. Translations are machine generated, so may not be an exact or complete translation, and the mm Hub cannot guarantee the accuracy of translated content. The mm and its employees will not be liable for any direct, indirect, or consequential damages (even if foreseeable) resulting from use of the Google Translate feature. For further support with Google Translate, visit Google Translate Help.

The Multiple Myeloma Hub is an independent medical education platform, sponsored by Bristol Myers Squibb, GSK, Legend Biotech, Pfizer, and Roche. Funders are allowed no direct influence on our content. The levels of sponsorship listed are reflective of the amount of funding given. View funders.

Now you can support HCPs in making informed decisions for their patients

Your contribution helps us continuously deliver expertly curated content to HCPs worldwide. You will also have the opportunity to make a content suggestion for consideration and receive updates on the impact contributions are making to our content.

Find out more

Create an account and access these new features:

Bookmark content to read later

Select your specific areas of interest

View multiple myeloma content recommended for you

Defining the significance of MGUS: the bone marrow microenvironment is compromised from an early stage in MM

Featured:

Multiple myeloma (MM) remains an incurable disease despite the ability to readily detect its precursor states: monoclonal gammopathy of unknown significance (MGUS), and smoldering MM (SMM). Although early intervention is an attractive approach to treatment, premalignancy does not always lead to progression. Therefore, comprehensive molecular characterization of the tumor microenvironment and the host immune response is required to understand disease progression further.1

In a recent study, Oksana Zavidij from the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and colleagues aimed to elucidate the transcriptomic alterations within the immune microenvironment in disease progression, by performing single-cell RNA-seq (scRNA-seq) on patient samples across all stages of MM. This study was published in Nature Cancer.1

Methods

- scRNA-seq was performed on bone marrow (BM) samples that were collected at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute from patients with MGUS (n = 5 patients), low-risk SMM (n = 3), high-risk SMM (n = 8), or newly diagnosed MM (n = 7), as well as healthy donors (n = 9)

- CD138− or CD45+ cell fractions were isolated using magnetic-activated cell sorting and in silico cell filtering based on gene expression

- Approximately 19,000 CD45+/CD138− cells from the microenvironment were sequenced

- 21 subpopulations of cells were isolated by clustering cells based on the gene expression profile

- Using the expression of known marker genes and finding the top differentially expressed genes for each cluster, cells were classified into ten broad types, ranging from hematopoietic progenitor cells and pre-B cells to mature populations engaged in the immune response

- Sequencing data was validated by performing mass cytometry by time-of-flight (CyTOF) on BM aspirates of patients with MGUS, SMM and MM (n = 13), and healthy BM controls (n = 4)

Results1

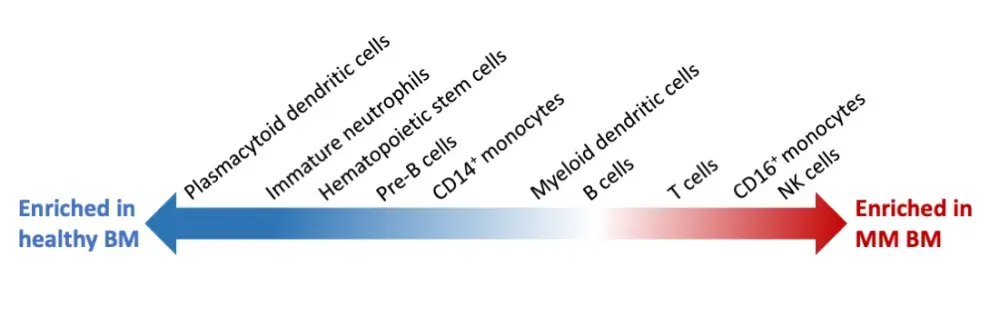

The tumor microenvironment changes considerably during myeloma progression, starting at the MGUS stage with increased populations of natural killer (NK) cells, T cells, and nonclassical monocytes (Figure 1). At the SMM stage, there is an early accumulation of regulatory and gamma-delta T cells, followed by loss of CD8+ memory populations, and an increase in interferon (IFN) signaling. At the MM stage, CD14+ monocytes show a loss of antigen presentation through dysregulation of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) type II genes, which leads to T cell suppression. Find a more detailed list of key findings in Table 1.

Figure 1. Adapted representation of immune cell composition changes between healthy and multiple myeloma bone marrow samples1

Table 1. Summary of key findings from scRNA-seq and CyTOF analysis in the microenvironment of bone marrow samples from patients with MGUS, SMM, and MM1

|

BM, bone marrow; CyTOF, cytometry by time-of-flight; HLA-DR, human leukocyte antigen DR isotype; MGUS, monoclonal gammopathy of unknown significance; MHC, major histocompatibility complex; MM, multiple myeloma; NK, natural killer; scRNA-seq, single-cell RNA-seq; SMM, smoldering MM |

|

|

The composition of the BM microenvironment changes early in MM progression (Figure 1) |

|

|

Increased Treg numbers and patient-specific heterogeneity in noncytotoxic T cells |

|

|

Cytotoxic T cell populations shifted toward effector phenotype during disease progression |

|

|

IFN response was seen across immune cell types in the MM samples |

|

|

CD14+ monocytes in the SMM and MM microenvironment showed defective antigen presentation due to intracellular accumulation of HLA-DR |

|

|

CD14+ monocytes in the BM microenvironment can promote the proliferation of myeloma cells and suppress T cell activation |

|

Conclusions and further discussion

During the 6th World Congress on Controversies in Multiple Myeloma (COMy) Meeting, Irene Ghobrial from the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, and one of the corresponding authors of this study presented the results right before their publication.2 Figure 2 represents a visual summary of the alterations observed in the immune microenvironment during progression to MM. These results are heterogeneous across patients and, despite the small sample size, could help develop future strategies on immune-based biomarkers for patient stratification and therapeutic targets to prevent progression to active disease.1

In her talk, she highlighted the importance of developing a comprehensive analysis of MM evolution, combining the genetic and epigenetic events in the plasma cell with tumor microenvironment regulation of the disease activation through immune and non-immune cells. With that aim, her group is working on what they call “Precision Prevention”: identifying signatures of expression that include both, plasma cells and microenvironment, and could potentially lead to personalized early treatment decision.2,3

It is essential to read these data in the context of an aging population with an increased cellular senescence burden. During the last COMy 2020, Gordon Cook, University of Leeds, gave us an overview of the immune status in MM and how the cellular senescence also affects the immune system.4

The so-called immunosenescence is a gradual deterioration of immune function brought on by the natural aging process. Changes in the number and function of hematopoietic stem cells have been described, entailing a decreased diversity of functional T cells, increasing pro-inflammatory cytokines, and leading to a chronic inflammatory state with advancing age. This state is one of the multiple reasons why in the elderly population there is an increased incidence of metabolic diseases, infections, frailty, and ultimately, cancer.4

Crucial advances on the evolution of MM will be achieved with the future results from the PROMISE study (NCT03689595): the first US cancer screening study for MM where investigators want to analyze samples from 50,000 high-risk individuals, defined as African American > 45 years, or people with a first-degree relative with MM. They estimate to be able to identify at least 3,000 positive cases to study thoroughly, and potentially prevent MM precursor progression to active disease.2

In conclusion, it is possible now to confirm a multilayered immune modulation that can be present at the early stages of MM. The prognostic power of this signature needs to be further elucidated within the heterogeneity of patients with MGUS, SMM, and MM.

Expert Opinion

“This study showed that the immune microenvironment is compromised even at the MGUS stage. It helps us understand that MGUS is not as benign as we thought it was. It also helps us understand the steps of immune dysregulation that occur as the patient transitions from MGUS to smoldering MM to overt MM. The hope is that we use this knowledge to develop specific immunotherapy that can delay or prevent progression.”

Irene Ghobrial

Irene GhobrialReferences

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statements:

The content was clear and easy to understand

The content addressed the learning objectives

The content was relevant to my practice

I will change my clinical practice as a result of this content

Your opinion matters

On average, how many patients with MGUS/smoldering MM do you see in a month?