All content on this site is intended for healthcare professionals only. By acknowledging this message and accessing the information on this website you are confirming that you are a Healthcare Professional. If you are a patient or carer, please visit the International Myeloma Foundation or HealthTree for Multiple Myeloma.

The mm Hub website uses a third-party service provided by Google that dynamically translates web content. Translations are machine generated, so may not be an exact or complete translation, and the mm Hub cannot guarantee the accuracy of translated content. The mm and its employees will not be liable for any direct, indirect, or consequential damages (even if foreseeable) resulting from use of the Google Translate feature. For further support with Google Translate, visit Google Translate Help.

The Multiple Myeloma Hub is an independent medical education platform, sponsored by Bristol Myers Squibb, GSK, Legend Biotech, Pfizer, and Roche. Funders are allowed no direct influence on our content. The levels of sponsorship listed are reflective of the amount of funding given. View funders.

Now you can support HCPs in making informed decisions for their patients

Your contribution helps us continuously deliver expertly curated content to HCPs worldwide. You will also have the opportunity to make a content suggestion for consideration and receive updates on the impact contributions are making to our content.

Find out more

Create an account and access these new features:

Bookmark content to read later

Select your specific areas of interest

View multiple myeloma content recommended for you

Challenges and future directions for access to cell therapies: A global perspective

The treatment landscape for hematologic malignancies has rapidly evolved with the advent of cell therapies, and the number of cell therapies in preclinical and clinical development is continuously increasing. Cell therapies, such as chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells, offer remarkably effective and durable responses. However, access can be challenging due to development, cost of manufacturing, and distribution barriers.

During the 48th Annual Meeting of the European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (EBMT), a joint session titled "Access to novel cell therapies such as CAR T cells: challenges and strategies" was delivered by several speakers. Here, we present perspectives from different countries, including the US, Europe, Asia, and Latin America.

The use of cell therapies in the US is rapidly expanding, but disparities in access remain –Jeffery Auletta1 and Miguel Perales2

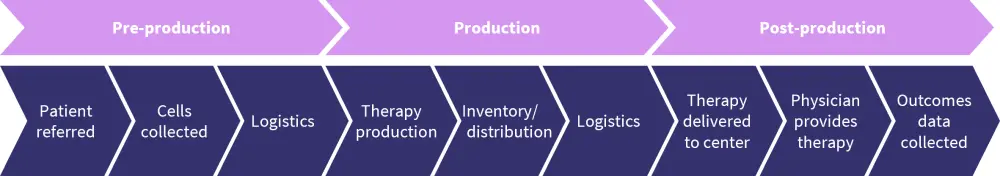

The three important phases in a patient's journey to CAR T-cell therapy are shown in Figure 1; at each of these phases, Auletta1 believes there is a potential barrier or outcome for ethnically diverse (ED) patients, which is largely due to patient needs, such as counseling, education, social support, and economic resources, but also due to the system itself.

Figure 1. A patient’s journey to CAR-T cell therapy*

*Adapted from Auletta.1

CAR T-cell therapy has been approved for several indications in the US, including non-Hodgkin lymphoma, acute lymphoblastic leukemia, and more recently, multiple myeloma.2 Experience with CAR T-cell therapies has rapidly increased between 2016 and 2021, particularly with commercial CAR T cells, with a total of 5,129 infusions in 4,886 patients. Of these patients, 74% received CAR T-cell therapy for non-Hodgkin lymphoma, 19% for acute lymphoblastic leukemia, and 6% for multiple myeloma. Most patients receiving CAR T-cell therapies during this time were aged ≤65 years, although there was also a fair representation of older patients.2

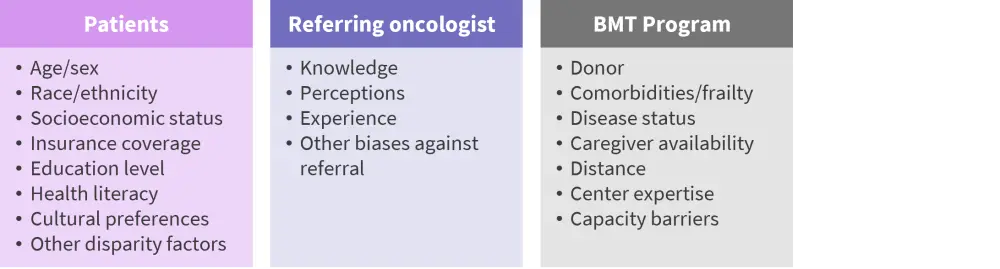

Data segregated by race showed that the majority of the patients receiving CAR T-cell therapies in the US between 2016 and 2021 were non-Hispanic white Caucasian patients, whereas a limited amount of these therapies were given to ED patients.1 The Hispanic, Latino, and African American populations were underrepresented with regard to delivery of CAR T-cell therapy and may face barriers in accessing hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) and cell therapies (Figure 2). In addition, data from the last 10 years show that the number of autologous HSCTs (auto-HSCTs) performed in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma has remained the same, and the majority were performed for white Caucasians.1

Figure 2. Barriers to hematopoietic stem cell transplantation/cell therapies*

BMT, Bone Marrow Transplant.

*Adapted from Auletta.1

Three clinical trials, ZUMA-7 (NCT03391466), BELINDA (NCT03570892), and TRANSFORM (NCT03575351), all of which randomized patients to CAR T-cell therapy as second-line for refractory/relapsed B-cell lymphoma, provide insights on some of the challenges of CAR T-cell therapies in a clinical trial.2 Although the inclusion criteria in all three trials were similar, the outcomes from the trials may have been impacted by differences in the definition of event-free survival, allowance of crossover, different CAR constructs used, bridging, and salvage therapies. The BELINDA trial also showed differences in the time to tisagenlecleucel infusion in patients treated in the US versus non-US countries (41 days vs 57 days, respectively).2

The differences in these studies present several questions about the trial outcomes and the future use of CAR T-cell therapies in the US2:

- Should different endpoints, such as overall survival, be considered?

- Which study design should be used (CAR T-cell therapy versus auto-HSCT or CAR T-cell therapy versus salvage)?

- How are patients receiving salvage therapy and showing a complete response or partial response being referred to bone marrow transplantation centers?

- Will CAR T-cell therapies as a second-line therapy exacerbate the issues of access?

- Do CAR T-cell therapies offer a better benefit–cost ratio?

Regional challenges in the US

A study looking at geographic access barriers demonstrated that patients living in the southern region of the US traveled longer distances to receive CAR T-cell therapies.1 In addition, another study revealed that before receiving CAR T-cell therapy, black pediatric patients had more previous lines of therapies (median, 5 vs 2; p < 0.0001), more relapses (median, 2 vs 1; p = 0.0105), and a higher rate of prior HSCT (71% vs 24%; p = 0.0122) compared with other patients; and achieved a lower rate of complete response (57% vs 86%; p = 0.007) and shorter overall survival (1-year rate, 43% vs 73%; p = 0.026). The disparities in access and outcomes of patients receiving CAR T cells are widely discussed today in the US.1

Several ways in which access and outcomes for ED patients can be improved include: (i) preventing ED patients from falling through the system by healthcare professionals and organizations taking personal and shared responsibility; (ii) addressing patients’ basic needs, such as providing financial assistance; (iii) educating patients on the importance of clinical trials; (iv) addressing cell therapy-specific barriers, the need for process improvement, and patient engagement; and (v) ensuring patient care coordination, including continuity of care.1

In Europe, the EBMT plans to improve access to cell therapy, as well as registries of its use – Christian Chabannon3

The EBMT is a non-profit organization that monitors the field of HSCT, allowing scientists to share their experiences and develop studies in collaboration. The Cellular Therapy Form (CTF) was developed by the Cellular Therapy and Immunobiology Working Party (CTIWP) in 2015 and collected data on the manufacturing process of CAR T cells. With the approval of the first commercial CAR T‑cell therapy in Europe in 2018, the CTIWP focused on collecting data on clinical outcomes and has provision to include patients from both commercial and clinical trial settings.

Gathering real-world data into the CTF poses several challenges, including limited resources (healthcare professionals and data managers) at treatment centers, the quality of information technology (IT) systems and recent changes in IT systems that support the EBMT registry, compliance with global data protection regulation, and obtaining patients’ consent to transfer individual-level data to a third party. In addition, CAR T-cell administration occurs in a complex therapeutic environment allowing multimodal sequential infusions of cellular therapies, making data collection more challenging.

There are several initiatives that the EMBT is undertaking to improve access to cell therapies and to enhance the EBMT registry, including:

- Collaborating with Novartis, Kite/Gilead, and Celgene regarding post-authorization safety studies to collect data.

- Collecting real-world data for CAR T cells, including addition of the CTF to the EBMT registry.

- Organizing a European meeting focused on novel cell therapies: the annual European CAR T-cell Meeting began in 2019 in collaboration with the EBMT and the European Hematology Association.

- Identifying centers in Europe that are involved in designing, developing, and evaluating innovative CAR T-cell therapies.

- Involving several working parties and committees in CAR T-cell administration and evaluation.

- Initiating the EBMT GoCART initiative; a multi-stakeholder coalition, which includes patient representatives and promotes patient access to cellular therapies.

Improving access to CAR T cells in the Asia-Pacific area will go hand in hand with significant progress in the HSCT field – Shinichiro Okamoto4

The Asia-Pacific Blood and Marrow Transplantation Group (APBMT) conducted a survey that showed that in only 8 out of 20 participating countries, >50% of patients eligible for HSCT could receive it. Similarly, access to CAR T-cell therapies is also challenging; they are available only in nine countries that participated in the survey, mainly in transplant centers and primarily through clinical trials.

Some of the shared barriers and challenges for HSCTs and CAR-based therapies include financial constraints of patients, inadequate funding from the government, lack of insurance, an inadequate number of centers for HSCTs, and the availability of apheresis facilities. Differences in regulations across Asia, including some countries having no cell therapy-specific regulations, is also a complex challenge. CAR T-cell products that are not widely used and have less established efficacy fall under the Act for Regenerative Medicine rather than the Act for HSCTs.

During their presentation, Okamoto suggested several points for improvement:

- Regarding production costs, the transposon or piggyBac is a low-cost approach to genetically engineer lymphocytes, offering moderate transduction efficiency compared with the high-cost retroviral or lentiviral vector approach.

- Geographic access to centers providing CAR T cells and other cell therapies can be improved by creating a regional network of transplant centers (e.g., there is a network of centers in nine areas in Japan in collaboration with the Japanese Stem Cell Transplantation and Cellular Therapy, Japan Marrow Donor Program, Cord Blood Bank, and Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare).

- The quality of centers developing CAR T-cell therapies can be improved using a multi-level approach guided by the JACIE standards.

- International data sharing can be enhanced by feeding data into CIBMTR from APBMT participating countries.

- Lastly, payment based on the milestone basis or allogeneic platforms for CAR T cells should also be considered.

Reducing costs of manufacturing will be the cornerstone of access to cell therapies in Latin America – Nelson Hamerschlak5

Despite several initiatives and ongoing clinical trials, national and international partnerships could help develop cell therapy in Latin America. The high cost of CAR T-cell therapies is not sustainable for health insurance companies or health systems in low- and middle-income countries; it restricts access, particularly for underserved populations, and creates difficulties for the pharmaceutical industry to maximize stockholder value. The cost can be significantly reduced by using technology and distributing manufacturing to place-of-care rather than the company manufacturing site. The Latin America Consortium is currently establishing a global network of place-of-care manufacturing facilities, and academic alternatives are also being investigated, mainly in Brazil.

Improving access and quality of CAR T-cell therapies is challenging due to pharmaceutical companies submitting their dossiers to few Latin America regulatory agencies. There is also a need for greater adherence from transplant and cell therapy centers in Latin America to the Foundation for the Accreditation of Cellular Therapies (FACT) and JACIE standards, as well as a cell therapies cases register.

Conclusion

This overview of perspectives from various regions summarizes different challenges that hematologists and patients currently face globally. As the cost of cell therapies is a significant factor in most countries, alternative methods, such as manufacturing CAR T cells at the place-of-care, may be considered in some countries. Addressing barriers to access will require collaboration across CAR T-cell therapy stakeholders, including professional cell therapy organizations facilitating collaboration, exchanging knowledge on vectors, and setting up centers.

References

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statements:

The content was clear and easy to understand

The content addressed the learning objectives

The content was relevant to my practice

I will change my clinical practice as a result of this content

Your opinion matters

On average, how many patients with MGUS/smoldering MM do you see in a month?